Regional forms of shamanism

Being a Hmong shaman is a vocation; their primary role is to bring harmony to the individual, their family, and their community within their environment by performing rituals, usually through trance.

Before the sacred cockfight, The Hmong of south-east Guizhou cover a rooster with a piece of red cloth and then hold it up to worship and sacrifice to the Heaven and the Earth.

[1] In a 2010 trial of a Hmong from Sheboygan, Wisconsin charged with staging a cockfight, it was stated that the roosters were "kept for both food and religious purposes",[2] and the case ended in an acquittal.

[2] In addition to the spiritual dimension, Hmong shamans attempt to treat many physical illnesses through the use of the text of sacred words (khawv koob).

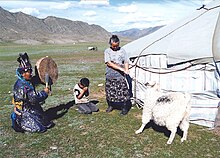

[10] Mongolian classics, such as The Secret History of the Mongols, provide details about male and female shamans serving as exorcists, healers, rainmakers, oneiromancers, soothsayers, and officials.

The "Guardian-Spirits" were made up of the souls of smaller shamans (böge) and shamanesses (idugan) and were associated with a specific locality (including mountains, rivers, etc.)

Babaylans were held in such high esteem because of their ability to negate the dark magic of an evil datu or spirit and heal the sick or the wounded.

[20] In modern Philippine society, their roles have largely been taken over by folk healers, which are now predominantly male, while some are still being falsely accused as 'witches', which has been inputted by Spanish colonialism.

[32][31] When the People's Republic of China was formed in 1949 and the border with Russian Siberia was formally sealed, many nomadic Tungus groups (including the Evenki) that practiced shamanism were confined in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia.

Animals are one of the most important elements of indigenous religion in Central Eurasia because of the role they play in the survival of the nomadic civilizations of the steppes as well as sedentary populations living on land not conducive to agriculture.

[35] As a religion of nature, shamanism throughout Central Eurasia held particular reverence for the relations between sky, earth and water and believed in the mystical importance of trees and mountains.

Shamanism in Central Eurasia also places a strong emphasis on the opposition between summer and winter, corresponding to the huge differences in temperature common in the region.

The harsh conditions and poverty caused by the extreme temperatures drove Central Eurasian nomads throughout history to pursue militaristic goals against their sedentary neighbors.

In this role they took on tasks such as healing, divination, appealing to ancestors, manipulating the elements, leading lost souls and officiating public religious rituals.

Shamans in ecstasy displayed unusual physical strength, the ability to withstand extreme temperatures, the bearing of stabbing and cutting without pain, and the heightened receptivity of the sense organs.

Many shamans practice ventriloquism and make use of their ability to accurately imitate the sounds of animals, nature, humans and other noises in order to provide the audience with the ambiance of the journey.

Theyyam or "theiyam" in Malayalam - a south Indian language - is the process by which a Priest invites a Hindu god or goddess to use his or her body as a medium or channel and answer other devotees' questions.

[56] Some of the prehistoric peoples who once lived in Siberia and other parts of Central and Eastern Eurasia have dispersed and migrated into other regions, bringing aspects of their cultures with them.

Eskimo groups inhabit a huge area stretching from eastern Siberia through Alaska and Northern Canada (including Labrador Peninsula) to Greenland.

[84] The Russian linguist Menovshikov (Меновщиков), an expert of Siberian Yupik and Sireniki Eskimo languages (while admitting that he is not a specialist in ethnology)[85] mentions, that the shamanistic seances of those Siberian Yupik and Sireniki groups he has seen have many similarities to those of Greenland Inuit groups described by Fridtjof Nansen,[86] although a large distance separates Siberia and Greenland.

[92] Although many Native American and First Nations cultures have traditional healers, singers, mystics, lore-keepers and medicine people, none of them ever used, or use, the term "shaman" to describe these religious leaders.

[94] From the colonial era, up until the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978, it was illegal for Indigenous people to practice traditional religion and sacred ceremonies.

[98] In addition to curanderos use of ayahuasca and their ritualized ingestion of mescaline-bearing San Pedro cactuses (Echinopsis pachanoi) for the divination and diagnosis of sorcery, north-coastal shamans are famous throughout the region for their intricately complex and symbolically dense healing altars called mesas (tables).

[101] In several tribes living in the Amazon rainforest, the spiritual leaders also act as managers of scarce ecological resources[102][103][104] The rich symbolism in Tukano culture has been documented in field works[102][105][106] even in the last decades of the 20th century.

[107] Among the Mapuche people of Chile, a machi is usually a woman who serves the community by performing ceremonies to cure diseases, ward off evil, influence the weather and harvest, and by practicing other forms of healing such as herbalism.

[116] On the island of Papua New Guinea, indigenous tribes believe that illness and calamity are caused by dark spirits, or masalai, which cling to a person's body and poison them.

Besides healing, contact with spiritual beings, involvement in initiation and other secret ceremonies, they are also enforcers of tribal laws, keepers of special knowledge and may "hex" to death one who breaks a social taboo by singing a song only known to the "clever men".

[citation needed] In Mali, Dogon sorcerers (both male and female) communicate with a spirit named Amma, who advises them on healing and divination practices.

Harner has faced criticism for taking pieces of diverse religions out of their cultural contexts in an attempt to create "universal" shamanistic practices.

Some neoshamans focus on the ritual use of entheogens,[128] and also embrace the philosophies of chaos magic[citation needed] while others (such as Jan Fries)[129] have created their own forms of shamanism.