Nazi book burnings

These included books written by Jewish, half-Jewish, communist, socialist, anarchist, liberal, pacifist, and sexologist authors among others.

[4] On April 8, 1933, the Main Office for Press and Propaganda of the German Student Union (DSt) proclaimed a nationwide "Action against the Un-German Spirit", which was to climax in a literary purge or "cleansing" ("Säuberung") by fire.

The black-lists ... ranged from Bebel, Bernstein, Preuss, and Rathenau through Einstein, Freud, Brecht, Brod, Döblin, Kaiser, the Mann brothers, Zweig, Plievier, Ossietzky, Remarque, Schnitzler, and Tucholsky, to Barlach, Bergengruen, Broch, Hoffmannsthal, Kästner, Kasack, Kesten, Kraus, Lasker-Schüler, Unruh, Werfel, Zuckmayer, and Hesse.

[5]Local chapters were to supply the press with releases and commissioned articles, sponsor well-known Nazis to speak at public gatherings, and negotiate for radio broadcast time.

This was, however, a false comparison, as the "book burnings" at those historic events were not acts of censorship, nor destructive of other people's property, but purely symbolic protests, destroying only one individual document of each title, for a grand total of 12 individual documents, without any attempt to suppress their content, whereas the Student Union burned tens of thousands of volumes, all they could find from a list comprising around 4000 titles.

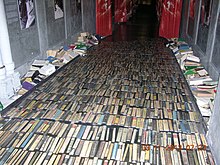

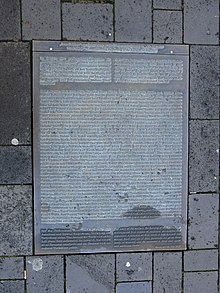

[9][10][11][12] The looted material was witnessed by the international press being loaded on to a truck and, on 10 May, it was taken to the Bebelplatz square at the State Opera, and burned them along with volumes from elsewhere.

The scripted rituals of this night called for high Nazi officials, professors, rectors, and student leaders to address the participants and spectators.

At the meeting places, students threw the pillaged, banned books into the bonfires with a great joyous ceremony that included live music, singing, "fire oaths," and incantations.

In his speech – which was broadcast on the radio – Goebbels' referred to the authors whose books were being burned as "Intellectual filth" and "Jewish asphalt literati".

Nonetheless, in thirty four university towns across Germany the "Action against the Un-German Spirit" was a success, enlisting widespread newspaper coverage.

And in some places, notably Berlin, radio broadcasts brought the speeches, songs, and ceremonial incantations "live" to countless German listeners.

[19] Among the other German-speaking authors whose books student leaders burned were: Vicki Baum, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, Franz Boas, Albert Einstein, Friedrich Engels, Etta Federn, Lion Feuchtwanger, Marieluise Fleißer, Leonhard Frank, Sigmund Freud, Iwan Goll, Jaroslav Hašek, Werner Hegemann, Hermann Hesse, Ödön von Horvath, Heinrich Eduard Jacob, Franz Kafka, Georg Kaiser, Alfred Kerr, Egon Kisch, Siegfried Kracauer, Theodor Lessing, Alexander Lernet-Holenia, Karl Liebknecht, Georg Lukács, Rosa Luxemburg, Klaus Mann, Thomas Mann, Ludwig Marcuse, Karl Marx, Robert Musil, Carl von Ossietzky,[16] Erwin Piscator, Alfred Polgar, Gertrud von Puttkamer, Erich Maria Remarque,[16] Ludwig Renn, Joachim Ringelnatz, Joseph Roth, Nelly Sachs, Felix Salten,[20] Anna Seghers, Abraham Nahum Stencl, Carl Sternheim, Bertha von Suttner, Ernst Toller, Frank Wedekind, Franz Werfel, Grete Weiskopf, and Arnold Zweig.

The burning of the books represents a culmination of the persecution of those authors whose oral or written opinions were opposed to Nazi ideology.

Some of them died in concentration camps, due to the consequences of the conditions of imprisonment, or were executed (like Carl von Ossietzky, Erich Mühsam, Gertrud Kolmar, Jakob van Hoddis, Paul Kornfeld, Arno Nadel, Georg Hermann, Theodor Wolff, Adam Kuckhoff, Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen, and Rudolf Hilferding).

[24] Because of the shift in political power and the blatant control and censorship demonstrated by the Nazi Party, 1933 saw a “mass exodus of German writers, artists, and intellectuals".

Among the authors whose books were available upon the library's opening were Albert Einstein, Maxim Gorki, Helen Keller, Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann, and many others.

[27] Rabbi Stephen Wise, who spoke at the inaugural dinner, had led a protest at Madison Square Garden on the day of the book burning, and was an advocate of the Zionist movement.

Thomas Mann, whose books were part of the library's collection, is quoted as saying that "what happened in Germany convinced me more and more of the value of Zionism for the Jew".

Publications from urban areas like the Miami Herald, Honolulu Star-Bulletin and the Philadelphia Inquirer, leaned towards a more critical stance on the book burnings and Nazi regime.

The Tennessee newspaper described the event in a very straightforward manner, calling Goebbels the “minister of enlightenment.” Similarly, the Delaware Morning News described the behavior of the Germans as “childish.” In 1946, the Allied occupation authorities drew up a list of over 30,000 titles, ranging from school books to poetry and including works by such authors as von Clausewitz.