Neanderthal behavior

It includes the Mousterian stone tool industry as well as the abilities to maintain and maybe create fire, build cave hearths, craft at least simple clothes similar to blankets and ponchos, make use of medicinal plants, treat severe injuries, store food, and use various cooking techniques such as roasting, boiling, and smoking.

A number of examples of symbolic thought and Palaeolithic art have been inconclusively attributed to Neanderthals, namely possible ornaments made from bird claws and feathers, shells, collections of unusual objects including crystals and fossils, and engravings.

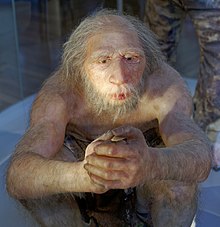

French palaeontologist Marcellin Boule authored several publications, among the first to establish palaeontology as a science, detailing the specimen, but reconstructed him as slouching, ape-like, and a distant offshoot of modern humans.

The image of the unevolved Neanderthal was reproduced for several decades and popularised in prehistoric fiction works, such as the 1911 The Quest for Fire by J.-H. Rosny aîné and the 1927 The Grisly Folk by H. G. Wells in which they are depicted as monsters.

[6][7][8] Still, in modern popular culture, the "caveman" archetype often mocks Neanderthals as primitive, hunchbacked, knuckle-dragging, club-wielding, grunting, nonsocial characters driven solely by animal instinct.

[4] In literature, they are sometimes depicted as brutish or monstrous, such as Elizabeth Marshall Thomas' The Animal Wife, but sometimes with a civilised but unfamiliar culture, as in Björn Kurtén's Dance of the Tiger, and Jean M. Auel's Clan of the Cave Bear and her Earth's Children series.

[12] Indicated from various ailments resulting from high stress at a low age, such as stunted growth, British archaeologist Paul Pettitt hypothesised that children of both sexes were put to work directly after weaning;[13] and American palaeonthropologist Erik Trinkaus suggested that, upon reaching adolescence, an individual may have been expected to join in hunting large and dangerous game.

[18] British anthropologist Eiluned Pearce and Cypriot archaeologist Theodora Moutsiou speculated that Neanderthals were possibly capable of forming geographically expansive ethnolinguistic tribes encompassing upwards of 800 people, based on the transport of obsidian up to 300 km (190 mi) from the source.

[37] There is some evidence of conflict: a skeleton from La Roche à Pierrot, France, showing a healed fracture on top of the skull apparently caused by a deep blade wound,[38] and another from Shanidar Cave, Iraq, with a rib lesion characteristic of projectile weapon injuries.

[72] Neanderthals exploited marine resources on the Iberian, Italian and Peloponnesian Peninsulas, where they waded or dove for shellfish,[71][73][74] as early as 150,000 years ago at Cueva Bajondillo, Spain, similar to the fishing record of modern humans.

[83] Dental tartar from Grotte de Spy, Belgium, indicates the inhabitants had a meat-heavy diet including woolly rhinoceros and mouflon sheep, while also regularly consuming mushrooms.

[88][89] Neanderthal tooth size had a decreasing trend after 100,000 years ago, which could indicate an increased dependence on cooking or the advent of boiling, a technique that would have softened food.

[104] It has been hypothesised to have functioned as body paint, and analyses of pigments from Pech de l'Azé, France, indicates they were applied to soft materials (such as a hide or human skin).

[108][94] Excavated from 1949 to 1963 from the French Grotte du Renne, Châtelperronian beads made from animal teeth, shells and ivory were found associated with Neanderthal bones.

[125] In 2018, some red-painted dots, disks, lines and hand stencils on the cave walls of the Spanish La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Doña Trinidad were dated to be older than 66,000 years ago, prior to the arrival of modern humans in Western Europe.

[140] The archaeological record demonstrates a long 150,000-year stagnation in Neanderthal lithic innovation,[141] which may have followed from the low population density and high injury rate, preventing especially complex technologies from being taught to the next generation.

[150][151] A wound on the neck of an African wild ass from Umm el Tlel, Syria, was likely inflicted by a heavy Levallois-point javelin,[152] and bone trauma consistent with habitual throwing has been reported in Neanderthals.

[78] The Châtelperronian in central France and northern Spain is a distinct industry from the Mousterian, and is controversially hypothesised to represent a culture of Neanderthals borrowing (or by process of acculturation) tool-making techniques from immigrating modern humans, crafting bone tools and ornaments.

[174] In 1990, two 176,000-year-old ring structures, several metres wide, made of broken stalagmite pieces, were discovered in a large chamber more than 300 m (980 ft) from the entrance within Grotte de Bruniquel, France.

Building complex structures so deep in a cave is unprecedented in the archaeological record, and indicates sophisticated lighting and construction technology, and great familiarity with subterranean environments.

Remains of Middle Palaeolithic stone tools on Greek islands have been alleged to indicate early seafaring by Neanderthals in the Ionian Sea possibly starting as far back as 150,000 to 200,000 years ago.

Individuals with severe head and rib traumas (which would have caused massive blood loss) indicate they had some manner of dressing major wounds, such as bandages made from animal skin.

[42] An individual at Cueva del Sidrón, Spain, seems to have been medicating a dental abscess using poplar—which contains salicylic acid, the active ingredient in aspirin—and there were also traces of the antibiotic-producing Penicillium chrysogenum.

[92] At the Kebara Cave in Israel, plant remains which have historically been used for their medicinal properties were found, including the common grape vine, the pistachios of the Persian turpentine tree, ervil seeds and oak acorns.

[192] Sites such as La Ferrassie in France or Shanidar in Iraq may imply the existence of mortuary centers or cemeteries in Neanderthal culture due to the number of individuals found buried at them.

[192] The debate on Neanderthal funerals has been active since the 1908 discovery of La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 in a small, artificial hole in a cave in southwestern France, very controversially postulated to have been buried in a symbolic fashion.

[193][194][195] Another grave at Shanidar Cave, Iraq, was associated with the pollen of several flowers that may have been in bloom at the time of deposition—yarrow, centaury, ragwort, grape hyacinth, joint pine and hollyhock.

[196] The medicinal properties of the plants led American archaeologist Ralph Solecki to claim that the man buried was some leader, healer, or shaman, and that "The association of flowers with Neanderthals adds a whole new dimension to our knowledge of his humanness, indicating that he had 'soul' ".

[101] In 1962, Italian palaeontologist Alberto Blanc believed a skull from Grotta Guattari, Italy, had evidence of a swift blow to the head—indicative of ritual murder—and a precise and deliberate incising at the base to access the brain.

[100] In 2019, Gibraltarian palaeoanthropologists Stewart, Geraldine, and Clive Finlayson and Spanish archaeologist Francisco Guzmán speculated that the golden eagle had iconic value to Neanderthals like in some recent societies.