History of rail transport in Germany

Modern German rail history officially began with the opening of the steam-powered Bavarian Ludwig Railway between Nuremberg and Fürth on 7 December 1835.

A wagonway operation was illustrated in Germany in 1556 by Georgius Agricola (image right) in his work De re metallica.

While business-minded people like Friedrich Harkort and Friedrich List saw in the railway the possibility of stimulating the economy and overcoming the patronization of little states, and were already starting railway construction in the 1820s and early 1830s, others feared the fumes and smoke generated by locomotives or saw their own livelihoods threatened by them.

In the 1830s, the growing liberal middle classes supported railways as a progressive innovation with benefits for the German people in general as well as for the shareholders in the joint stock companies that built and operated the railroads.

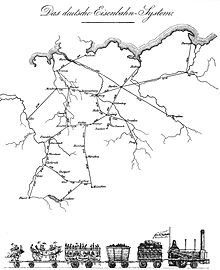

[3] Economist Friedrich List, speaking for the liberals, summed up the advantages to be derived from the development of the railway system in 1841: Lacking a technological base at first, the Germans imported their engineering and hardware from Britain, but quickly learned the skills needed to operate and expand the railways.

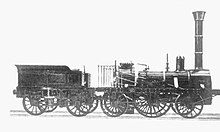

It was officially opened on 7 December 1835 with a journey from Nuremberg to Fürth after earlier test runs had been carried out with the locomotive Adler, built by Stephenson and Co. in Newcastle upon Tyne.

The takeoff stage of economic development came with the railroad revolution in the 1840s, which opened up new markets for local products, created a pool of middle managers, increased the demand for engineers, architects and skilled machinists and stimulated investments in coal and iron.

Economist Friedrich List summed up the advantages to be derived from the development of the railway system in 1841:[6] # As a means of national defence, it facilitates the concentration, distribution and direction of the army.

Lacking a technological base at first, the Germans imported their engineering and hardware from Britain, but quickly learned the skills needed to operate and expand the railways.

For example, in 1837-39, Thomas Clarke Worsdell (1788–1862), chief coachbuilder of the Liverpool and Manchester Company, came to help engineer the railway linking Leipzig and Dresden.

Unlike the situation in France, the goal was support of industrialisation, and so, heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts, and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen.

Lehrte became an important railway hub, with routes to Berlin, Cologne, Hildesheim and Harburg in front of the gates of Hamburg.

On 1 September 1846, the last section (Frankfurt (Oder) – Bunzlau) of the 330-kilometre-long (210 mi) Lower Silesian-Märkisch Railway was opened, linking the two great cities of Prussia, Berlin and Breslau.

At the same time the main line of the Upper Silesian Railway that started in Breslau reached Gleiwitz in October of that year.

Three and a half months later, on 15 December 1846, the Berlin–Hamburg Railway went into service: a 286-kilometre-long (178 mi) diagonal connection between the two largest cities of what became the German Empire.

With the completion of the railway within Breslau on 3 February 1848 that connected its termini, there was now a continuous rail link from the Rhine to the Vistula And with the closure of a short gap between the William Railway in Upper Silesia and the Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway in Austrian Silesia on 1 September 1848, the first contiguous Central European network was formed, reaching as far as Deutz, right of the Rhine, in the west, Harburg in the north, Warsaw and Kraków in the east and as far as Gloggnitz at the northern foot of the Semmering Pass in the south.

In 1860 the Prussian Eastern Railway was extended to the Russian border beyond Eydtkuhnen (today Chernyshevskoye) in German East Prussia.

With the opening of the branch from Vilnius (German: Wilna)–Kaunas–Virbalis (German: Wirballen, Russian: Вержболово and Polish: Wierzbałowo) on the Saint Petersburg–Warsaw Railway to this border crossing near Kybartai, the first junction between the European standard gauge and the Russian broad gauge networks was established.

Following the unification of Germany in 1871, attitudes changed in Prussia; Otto von Bismarck, in particular, pressed for the development of a state railway system.

By 1880, Germany had 9,400 locomotives each annually pulling 43,000 passengers or 30,000 tons of freight, and forged ahead of France.

[14] As the main line network consolidated, railways were driven into the hinterland, serving local needs and commuter traffic.

In accordance with the "Dawes Plan", on 30 August 1924 the state railways were legally merged to form the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft (DRG, German State Railway Company), a private company, which was required to pay reparations of about 660 million Marks annually.

The focus was on fewer types but greater numbers of so-called Kriegsbauart or wartime designs for the transportation of large quantities of tanks, vehicles, troops and supplies.

During the Second World War, austere versions of the standard locomotives were produced to speed up construction times and minimize the use of imported materials.

[15] The rail yards were the main targets of the "transportation strategy" of the British and American strategic bombing campaign of 1944–45, and resulted in massive destruction of the system.

[16] After World War II, Germany (and the DRG) was divided into 4 zones: American, British, French and Soviet.

The DRG's (or DR's) successors were named Deutsche Bundesbahn (DB, German Federal Railways) in West Germany, and Deutsche Reichsbahn (DR, German State Railways) in East Germany kept the old name to hold tracking rights in western Berlin.

Unlike the DRG, which was a corporation, both the DB and the DR were federal state institutions, directly controlled by their respective transportation ministries.

In 1991 the new high speed lines Hannover-Fulda-Würzburg (280 km/h) and Mannheim-Stuttgart (250 km/h) were opened for service including the new ICE 1 train sets.

Train frequency rapidly increased on the existing East/West corridors; closed links which had formerly crossed the border were re-opened.

built 1906–1923