Negative temperature

This should be distinguished from temperatures expressed as negative numbers on non-thermodynamic Celsius or Fahrenheit scales, which are nevertheless higher than absolute zero.

Thermodynamic systems with unbounded phase space cannot achieve negative temperatures: adding heat always increases their entropy.

Bounded phase space is the essential property that allows for negative temperatures, and can occur in both classical and quantum systems.

As shown by Onsager, a system with bounded phase space necessarily has a peak in the entropy as energy is increased.

For example in Onsager's point-vortex analysis negative temperature is associated with the emergence of large-scale clusters of vortices.

[5] They wrote: The absolute temperature (Kelvin) scale can be loosely interpreted as the average kinetic energy of the system's particles.

The paradox is resolved by considering the more rigorous definition of thermodynamic temperature in terms of Boltzmann's entropy formula.

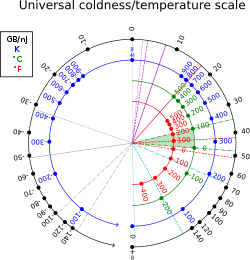

This reveals the tradeoff between internal energy and entropy contained in the system, with "coldness", the reciprocal of temperature, being the more fundamental quantity.

Because it avoids the abrupt jump from +∞ to −∞, β is considered more natural than T. Although a system can have multiple negative temperature regions and thus have −∞ to +∞ discontinuities.

The distribution of energy among the various translational, vibrational, rotational, electronic, and nuclear modes of a system determines the macroscopic temperature.

This is the "normal" condition in the macroscopic world, and is always the case for the translational, vibrational, rotational, and non-spin-related electronic and nuclear modes.

The simplest example, albeit a rather nonphysical one, is to consider a system of N particles, each of which can take an energy of either +ε or −ε but are otherwise noninteracting.

From elementary combinatorics, the total number of microstates with this amount of energy is a binomial coefficient: By the fundamental assumption of statistical mechanics, the entropy of this microcanonical ensemble is We can solve for thermodynamic beta (β = 1/kBT) by considering it as a central difference without taking the continuum limit: hence the temperature This entire proof assumes the microcanonical ensemble with energy fixed and temperature being the emergent property.

Since we started with over half the atoms in the spin-down state, this initially drives the system towards a 50/50 mixture, so the entropy is increasing, corresponding to a positive temperature.

While relaxation is fast in solids, it can take several seconds in solutions and even longer in gases and in ultracold systems; several hours were reported for silver and rhodium at picokelvin temperatures.

The Hamiltonian for a single mode of a luminescent radiation field at frequency ν is The density operator in the grand canonical ensemble is For the system to have a ground state, the trace to converge, and the density operator to be generally meaningful, βH must be positive semidefinite.

This was done by tuning the interactions of the atoms from repulsive to attractive using a Feshbach resonance and changing the overall harmonic potential from trapping to anti-trapping, thus transforming the Bose-Hubbard Hamiltonian from Ĥ → −Ĥ.

The negative temperature ensembles equilibrated and showed long lifetimes in an anti-trapping harmonic potential.