Grand canonical ensemble

The ensemble is also dependent on mechanical variables such as volume (symbol: V), which influence the nature of the system's internal states.

The grand potential Ω serves two roles: to provide a normalization factor for the probability distribution (the probabilities, over the complete set of microstates, must add up to one); and, many important ensemble averages can be directly calculated from the function Ω(µ, V, T).

[2] Grand ensembles are apt for use when describing systems such as the electrons in a conductor, or the photons in a cavity, where the shape is fixed but the energy and number of particles can easily fluctuate due to contact with a reservoir (e.g., an electrical ground or a dark surface, in these cases).

The grand canonical ensemble applies to systems of any size, small or large; it is only necessary to assume that the reservoir with which it is in contact is much larger (i.e., to take the macroscopic limit).

Alternatively, theoretical approaches can be used to model the influence of the connection, yielding an open statistical ensemble.

Even if the exact conditions of the system do not actually allow for variations in energy or particle number, the grand canonical ensemble can be used to simplify calculations of some thermodynamic properties.

As a result, the grand canonical ensemble can be highly inaccurate when applied to small systems of fixed particle number, such as atomic nuclei.

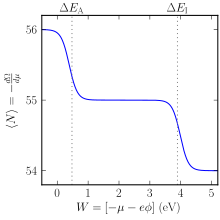

[4] The partial derivatives of the function Ω(µ1, …, µs, V, T) give important grand canonical ensemble average quantities:[1][6] Exact differential: From the above expressions, it can be seen that the function Ω has the exact differential First law of thermodynamics: Substituting the above relationship for ⟨E⟩ into the exact differential of Ω, an equation similar to the first law of thermodynamics is found, except with average signs on some of the quantities:[1] Thermodynamic fluctuations: The variances in energy and particle numbers are[7][8] Correlations in fluctuations: The covariances of particle numbers and energy are[1] The usefulness of the grand canonical ensemble is illustrated in the examples below.

In each case the grand potential is calculated on the basis of the relationship which is required for the microstates' probabilities to add up to 1.

In the special case of a quantum system of many non-interacting particles, the thermodynamics are simple to compute.

We can consider a region of the single-particle phase space with approximately uniform energy ϵi to be an "orbital" labelled i.

If the particles can be created out of energy during the dynamics of the system, then an associated µN term must not appear in the probability expression for the grand canonical ensemble.

In quantum mechanics, the grand canonical ensemble affords a simple description since diagonalization provides a set of distinct microstates of a system, each with well-defined energy and particle number.

The classical mechanical case is more complex as it involves not stationary states but instead an integral over canonical phase space.

The grand potential Ω is determined by the probability normalization condition that the density matrix has a trace of one,

The grand canonical ensemble can alternatively be written in a simple form using bra–ket notation, since it is possible (given the mutually commuting nature of the energy and particle number operators) to find a complete basis of simultaneous eigenstates |ψi⟩, indexed by i, where Ĥ|ψi⟩ = Ei|ψi⟩, N̂1|ψi⟩ = N1,i|ψi⟩, and so on.

In classical mechanics, a grand ensemble is instead represented by a joint probability density function defined over multiple phase spaces of varying dimensions, ρ(N1, … Ns, p1, … pn, q1, … qn), where the p1, … pn and q1, … qn are the canonical coordinates (generalized momenta and generalized coordinates) of the system's internal degrees of freedom.

For example, in a three-dimensional gas of monoatoms n = 3N, however in molecular gases there will also be rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom.

A well-known problem in the statistical mechanics of fluids (gases, liquids, plasmas) is how to treat particles that are similar or identical in nature: should they be regarded as distinguishable or not?

In the system's equation of motion each particle is forever tracked as a distinguishable entity, and yet there are also valid states of the system where the positions of each particle have simply been swapped: these states are represented at different places in phase space, yet would seem to be equivalent.

Although appearing benign at first, this leads to a problem of severely non-extensive entropy in the canonical ensemble, known today as the Gibbs paradox.

In this case the entropy and chemical potential are non-extensive but also badly defined, depending on a parameter (reservoir size) that should be irrelevant.

[1][note 5] In order to incorporate this fact, integrals are still carried over full phase space but the result is divided by which is the number of different permutations possible.