Degrees of freedom (physics and chemistry)

Similarly, the direction and speed at which a particle moves can be described in terms of three velocity components, each in reference to the three dimensions of space.

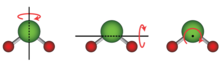

On the other hand, a system with an extended object that can rotate or vibrate can have more than six degrees of freedom.

In statistical mechanics, a degree of freedom is a single scalar number describing the microstate of a system.

Any atom or molecule has three degrees of freedom associated with translational motion (kinetic energy) of the center of mass with respect to the x, y, and z axes.

In special cases, such as adsorbed large molecules, the rotational degrees of freedom can be limited to only one.

A diatomic molecule has one molecular vibration mode: the two atoms oscillate back and forth with the chemical bond between them acting as a spring.

However, the much less abundant greenhouse gases keep the troposphere warm by absorbing infrared from the Earth's surface, which excites their vibrational modes.

One can also count degrees of freedom using the minimum number of coordinates required to specify a position.

Contrary to the classical equipartition theorem, at room temperature, the vibrational motion of molecules typically makes negligible contributions to the heat capacity.

example: if X1 and X2 are two degrees of freedom, and E is the associated energy: For example, in Newtonian mechanics, the dynamics of a system of quadratic degrees of freedom are controlled by a set of homogeneous linear differential equations with constant coefficients.

The description of a system's state as a point in its phase space, although mathematically convenient, is thought to be fundamentally inaccurate.

For example, intrinsic angular momentum operator (which corresponds to the rotational freedom) for an electron or photon has only two eigenvalues.

This discreteness becomes apparent when action has an order of magnitude of the Planck constant, and individual degrees of freedom can be distinguished.