Neptune

After Bouvard's death, the position of Neptune was mathematically predicted from his observations, independently, by John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier.

Neptune was subsequently directly observed with a telescope on 23 September 1846[2] by Johann Gottfried Galle within a degree of the position predicted by Le Verrier.

[22][23] Like the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), Neptune's atmosphere is composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, along with traces of hydrocarbons and possibly nitrogen, but contains a higher proportion of ices such as water, ammonia and methane.

[29] Because of its great distance from the Sun, Neptune's outer atmosphere is one of the coldest places in the Solar System, with temperatures at its cloud tops approaching 55 K (−218 °C; −361 °F).

Because Neptune was only beginning its yearly retrograde cycle, the motion of the planet was far too slight to be detected with Galileo's small telescope.

[36] Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesize that an unknown body was perturbing the orbit through gravitational interaction.

[37][40] Challis had, in fact, observed Neptune a year before the planet's subsequent discoverer, Johann Gottfried Galle, and on two occasions, 4 and 12 August 1845.

[45] Since 1966, Dennis Rawlins has questioned the credibility of Adams's claim to co-discovery, and the issue was re-evaluated by historians with the return in 1998 of the "Neptune papers" (historical documents) to the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

[51] Struve came out in favour of the name Neptune on 29 December 1846, to the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences,[52] after the colour of the planet as viewed through a telescope.

[55][56] In Mongolian, Neptune is called Dalain van (Далайн ван), reflecting its namesake god's role as the ruler of the sea.

In Malay, the name Waruna, after the Hindu god of seas, is attested as far back as the 1970s,[61] but was eventually superseded by the Latinate equivalents Neptun (in Malaysian[62]) or Neptunus (in Indonesian[63]).

[80][78] Very-high-pressure experiments at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory suggest that the top of the mantle may be an ocean of liquid carbon with floating solid 'diamonds'.

[84][91][92] Neptune's spectra suggest that its lower stratosphere is hazy due to condensation of products of ultraviolet photolysis of methane, such as ethane and ethyne.

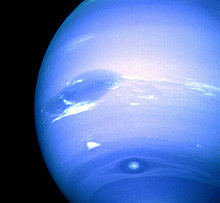

Early renderings of the two planets greatly exaggerated Neptune's colour contrast "to better reveal the clouds, bands and winds", making it seem deep blue compared to Uranus's off-white.

This field may be generated by convective fluid motions in a thin spherical shell of electrically conducting liquids (probably a combination of ammonia, methane and water),[89] resulting in a dynamo action.

The large quadrupole moment of Neptune may be the result of an offset from the planet's centre and geometrical constraints of the field's dynamo generator.

[102][103] Measurements by Voyager 2 in extreme-ultraviolet and radio frequencies revealed that Neptune has faint and weak but complex and unique aurorae; however, these observations were limited in time and did not contain infrared.

[104][105] Neptune's bow shock, where the magnetosphere begins to slow the solar wind, occurs at a distance of 34.9 times the radius of the planet.

[102] Neptune's weather is characterized by extremely dynamic storm systems, with winds reaching speeds of almost 600 m/s (2,200 km/h; 1,300 mph)—exceeding supersonic flow.

[119] In 1989, Voyager 2's Planetary Radio Astronomy (PRA) experiment observed around 60 lightning flashes, or Neptunian electrostatic discharges emitting energies over 7×108 J.

One is that the ice giants were not formed by core accretion but from instabilities within the original protoplanetary disc and later had their atmospheres blasted away by radiation from a nearby massive OB star.

[73] An alternative concept is that they formed closer to the Sun, where the matter density was higher, and then subsequently migrated to their current orbits after the removal of the gaseous protoplanetary disc.

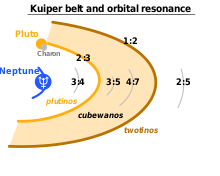

[140] This hypothesis of migration after formation is favoured due to its ability to better explain the occupancy of the populations of small objects observed in the trans-Neptunian region.

[141] The current most widely accepted[142][143][144] explanation of the details of this hypothesis is known as the Nice model, which is a dynamical evolution scenario that explores the potential effect of a migrating Neptune and the other giant planets on the structure of the Kuiper belt.

Over the age of the Solar System, certain regions of the Kuiper belt became destabilised by Neptune's gravity, creating gaps in its structure.

Unlike all other large planetary moons in the Solar System, Triton has a retrograde orbit, indicating that it was captured rather than forming in place; it was probably once a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt.

It can be outshone by Jupiter's Galilean moons, the dwarf planet Ceres and the asteroids 4 Vesta, 2 Pallas, 7 Iris, 3 Juno, and 6 Hebe.

Both Hubble and the adaptive-optics telescopes on Earth have made many new discoveries within the Solar System since the mid-1990s, with a large increase in the number of known satellites and moons around the outer planet, among others.

[89] In the infrared part of the spectrum, Neptune's storms appear bright against the cooler background, allowing the size and shape of these features to be readily tracked.

[193] A subsequent proposal, that was not selected, was for Argo, a flyby spacecraft to be launched in 2019, that would visit Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and a Kuiper belt object.