Nerve agent

Poisoning by a nerve agent leads to constriction of pupils, profuse salivation, convulsions, and involuntary urination and defecation, with the first symptoms appearing in seconds after exposure.

All such agents function the same way resulting in cholinergic crisis: they inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which is responsible for the breakdown of acetylcholine (ACh) in the synapses between nerves that control whether muscle tissues are to relax or contract.

Because of this, the first symptoms usually appear within 30 seconds of exposure and death can occur via asphyxiation or cardiac arrest in a few minutes, depending upon the dose received and the agent used.

[2] Initial symptoms following exposure to nerve agents (like Sarin) are a runny nose, tightness in the chest, and constriction of the pupils.

As the victim continues to lose control of bodily functions, involuntary salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal pain and vomiting will be experienced.

[7] Possible effects that can last at least up to two–three years after exposure include blurred vision, tiredness, declined memory, hoarse voice, palpitations, sleeplessness, shoulder stiffness and eye strain.

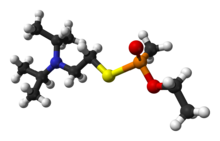

Nerve agents disrupt the nervous system by inhibiting the function of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase by forming a covalent bond with its active site, where acetylcholine would normally be broken down (undergo hydrolysis).

This same action also occurs at the gland and organ levels, resulting in uncontrolled drooling, tearing of the eyes (lacrimation) and excess production of mucus from the nose (rhinorrhea).

The reaction product of the most important nerve agents, including Soman, Sarin, Tabun and VX, with acetylcholinesterase were solved by the U.S. Army using X-ray crystallography in the 1990s.

The X-ray structures clarify important aspects of the reaction mechanism (e.g., stereochemical inversion) at atomic resolution and provide a key tool for antidote development.

[13] Some synthetic anticholinergics, such as biperiden,[15] may counteract the central symptoms of nerve agent poisoning more effectively than atropine, since they pass the blood–brain barrier better.

[14] Anticonvulsants, such as diazepam, may be administered to manage seizures, improving long term prognosis and reducing risk of brain damage.

It is only effective if taken prior to exposure and in conjunction with Atropine and Pralidoxime, issued in the Mark I NAAK autoinjector, and is ineffective against other nerve agents.

[21] Both purified acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase have demonstrated success in animal studies as "biological scavengers" (and universal targets) to provide stoichiometric protection against the entire spectrum of organophosphate nerve agents.

All of the compounds in this class were discovered and synthesized during or prior to World War II, led by Gerhard Schrader (later under the employment of IG Farben).

[27] The V-series is the second family of nerve agents and contains five well known members: VE, VG, VM, VR, and VX, along with several more obscure analogues.

[28] The most studied agent in this family, VX (it is thought that the 'X' in its name comes from its overlapping isopropyl radicals), was invented in the 1950s at Porton Down in Wiltshire, England.

Some insecticides such as demeton, dimefox and paraoxon are sufficiently toxic to humans that they have been withdrawn from agricultural use, and were at one stage investigated for potential military applications.

[41] This first class of nerve agents, the G-series, was accidentally discovered in Germany on December 23, 1936, by a research team headed by Gerhard Schrader working for IG Farben.

In January 1937, Schrader observed the effects of nerve agents on human beings first-hand when a drop of Tabun spilled onto a lab bench.

In 1935 the Nazi government had passed a decree that required all inventions of possible military significance to be reported to the Ministry of War, so in May 1937 Schrader sent a sample of Tabun to the chemical warfare (CW) section of the Army Weapons Office in Berlin-Spandau.

In 1939, a pilot plant for Tabun production was set up at Munster-Lager, on Lüneburg Heath near the German Army proving grounds at Raubkammer [de].

Tabun itself was so hazardous that the final processes had to be performed while enclosed in double glass-lined chambers with a stream of pressurized air circulating between the walls.

Three thousand German nationals were employed at Hochwerk, all equipped with respirators and clothing constructed of a poly-layered rubber/cloth/rubber sandwich that was destroyed after the tenth wearing.

Some incidents cited in A Higher Form of Killing: The Secret History of Chemical and Biological Warfare are as follows:[43] The plant produced between 10 000 and 30 000 tons of Tabun before its capture by the Soviet Army[citation needed] and moved, probably to Dzerzhinsk, USSR.

Though Sarin, Tabun and Soman were incorporated into artillery shells, the German government ultimately decided not to use nerve agents against Allied targets.

[46] This is detailed in Joseph Borkin's book The Crime and Punishment of IG Farben:[47] Speer, who was strongly opposed to the introduction of Tabun, flew Otto Ambros, I.G.

On the scale of the single Kurdish village of Halabja within its own territory, Iraqi forces did expose the populace to some kind of chemical weapons, possibly mustard gas and most likely nerve agents.

Thirty-two thousand tons of nerve and mustard agents had already been dumped into the ocean waters off the United States by the U.S. Army, primarily as part of Operation CHASE.

Scientists at the U.S. Army Research Laboratory engineered an LPAS system that can detect multiple trace amounts of toxic gases in one air sample.