Church of the East

[28] Continuing as a dhimmi community under the Rashidun Caliphate after the Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia.

[29] It established dioceses and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea and today's Iraq and Iran, to India, the Mongol kingdoms and Turkic tribes in Central Asia, and China during the Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries).

[citation needed] Drawing inspiration from Theodore of Mopsuestia, Babai the Great (551−628) expounded, especially in his Book of Union, what became the normative Christology of the Church of the East.

[57] Opposition to religious images eventually became the norm due to the rise of Islam in the region, which forbade any type of depictions of Saints and biblical prophets.

John of Cora (Giovanni di Cori), Latin bishop of Sultaniya in Persia, writing about 1330 of the East Syrians in Khanbaliq says that they had 'very beautiful and orderly churches with crosses and images in honour of God and of the saints'.

[60] An illustrated 13th-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel book written in Estrangela from northern Mesopotamia or Tur Abdin, currently in the State Library of Berlin, proves that in the 13th century the Church of the East was not yet aniconic.

[61] The Nestorian Evangelion preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France contains an illustration depicting Jesus Christ in the circle of a ringed cross surrounded by four angels.

[62] Three Syriac manuscripts from early 19th century or earlier – they were published in a compilation titled The Book of Protection by Hermann Gollancz in 1912 – contain some illustrations of no great artistic worth that show that use of images continued.

The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ.

[79] Shapur II attempted to dismantle the catholicate's structure and put to death some of the clergy including the catholicoi Simeon bar Sabba'e (341),[80] Shahdost (342), and Barba'shmin (346).

[83] The church grew considerably during the Sasanian period,[36] but the pressure of persecution led the Catholicos, Dadisho I, in 424 to convene the Council of Markabta of the Arabs and declare the Catholicate independent from "the western Fathers".

In 484 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, convened the Synod of Beth Lapat where he publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a spiritual authority.

[36] By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by the Church of the East included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including the Sasanian Empire, the Arabian Peninsula, with minor presence in the Horn of Africa, Socotra, Mesopotamia, Media, Bactria, Hyrcania, and India; and possibly also to places called Calliana, Male, and Sielediva (Ceylon).

He is known to have consecrated metropolitans for Damascus, for Armenia, for Dailam and Gilan in Azerbaijan, for Rai in Tabaristan, for Sarbaz in Segestan, for the Turks of Central Asia, for China, and possibly also for Tibet.

[36] Nestorian Christians made substantial contributions to the Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, particularly in translating the works of the ancient Greek philosophers to Syriac and Arabic.

[104] From at least the early 4th century, the Patriarch of the Church of the East provided the Saint Thomas Christians with clergy, holy texts, and ecclesiastical infrastructure.

After the Synod of Diamper in 1599, they installed Padroado Portuguese bishops over the local sees and made liturgical changes to accord with the Latin practice and this led to a revolt among the Saint Thomas Christians.

In 1661, Pope Alexander VII responded by sending a delegations of Carmelites headed by two Italians, one Fleming and one German priests to reconcile the Saint Thomas Christians to Catholic fold.

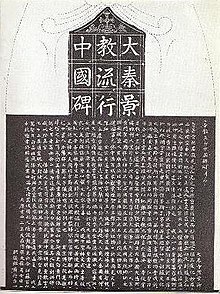

[112][113] The inscription on the Nestorian Stele, whose dating formula mentions the patriarch Hnanisho II (773–780), gives the names of several prominent Christians in China, including Metropolitan Adam, Bishop Yohannan, 'country-bishops' Yazdbuzid and Sargis and Archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan (Chang'an) and Gabriel of Sarag (Luoyang).

Marco Polo in the 13th century and other medieval Western writers described many Nestorian communities remaining in China and Mongolia; however, they clearly were not as active as they had been during Tang times.

During the rule of Genghis's grandson, the Great Khan Mongke, Nestorian Christianity was the primary religious influence in the Empire, and this also carried over to Mongol-controlled China, during the Yuan dynasty.

Small Nestorian communities were located further west, notably in Jerusalem and Cyprus, but the Malabar Christians of India represented the only significant survival of the once-thriving exterior provinces of the Church of the East.

This practice, which resulted in a shortage of eligible heirs, eventually led to a schism in the Church of the East, creating a temporarily Catholic offshoot known as the Shimun line.

[125] The Patriarch Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb (1539–58) caused great turmoil at the beginning of his reign by designating his twelve-year-old nephew Khnanishoʿ as his successor, presumably because no older relatives were available.

[54] These appointments, combined with other accusations of impropriety, caused discontent throughout the church, and by 1552 Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb had become so unpopular that a group of bishops, principally from the Amid, Sirt and Salmas districts in northern Mesopotamia, chose a new patriarch.

They elected a monk named Yohannan Sulaqa, the former superior of Rabban Hormizd Monastery near Alqosh, which was the seat of the incumbent patriarchs;[127] however, no bishop of metropolitan rank was available to consecrate him, as canonically required.

Franciscan missionaries were already at work among the Nestorians,[128] and, using them as intermediaries,[129] Sulaqa's supporters sought to legitimise their position by seeking their candidate's consecration by Pope Julius III (1550–55).

[143] Yahballaha's successor, Shimun IX Dinkha (1580–1600), who moved away from Turkish rule to Salmas on Lake Urmia in Persia,[144] was officially confirmed by the Pope in 1584.

[152] As the Shimun line "gradually returned to the traditional worship of the Church of the East, thereby losing the allegiance of the western regions",[153] it moved from Turkish-controlled territory to Urmia in Persia.

His younger cousin Yohannan Hormizd was locally elected to replace him in 1780, but for various reasons was recognised by Rome only as Metropolitan of Mosul and Administrator of the Catholics of the Alqosh party, having the powers of a Patriarch but not the title or insignia.

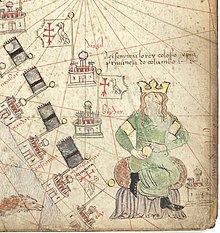

, identified as Christian due to the early Christian presence there)

[

99

]

in the contemporary

Catalan Atlas

of 1375.

[

100

]

[

101

]

The caption above the king of

Kollam

reads:

Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.

[

102

]

The black flags (

, identified as Christian due to the early Christian presence there)

[

99

]

in the contemporary

Catalan Atlas

of 1375.

[

100

]

[

101

]

The caption above the king of

Kollam

reads:

Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.

[

102

]

The black flags (

) on the coast belong to the

Delhi Sultanate

.

) on the coast belong to the

Delhi Sultanate

.