Network motif

[5][24][25] The computational research has focused on improving existing motif detection tools to assist the biological investigations and allow larger networks to be analyzed.

In expanded to include sharp contrast to exhaustive search, the computational time of the algorithm surprisingly is asymptotically independent of the network size.

If it is lower and if downward closure holds, FPF can abandon that path and not traverse further in this part of the tree; as a result, unnecessary computation is avoided.

Although Kashtan et al. tried to settle this drawback by means of a weighting scheme, this method imposed an undesired overhead on the running time as well a more complicated implementation.

Furthermore, RAND-ESU uses a novel analytical approach called DIRECT for determining sub-graph significance instead of using an ensemble of random networks as a Null-model.

This stage has been implemented simply by employing McKay's nauty algorithm,[28][29] which classifies each sub-graph by performing a graph isomorphism test.

Therefore, ESU finds the set of all induced k-size sub-graphs in a target graph by a recursive algorithm and then determines their frequency using an efficient tool.

Note that, this procedure ensures that the chances of visiting each leaf of the ESU-Tree are the same, resulting in unbiased sampling of sub-graphs through the network.

The probability of visiting each leaf is Πdpd and this is identical for all of the ESU-Tree leaves; therefore, this method guarantees unbiased sampling of sub-graphs from the network.

In summary, RAND-ESU is a very fast algorithm for NM discovery in the case of induced sub-graphs supporting unbiased sampling method.

Next, by means of a branch-and-bound method, the algorithm tries to find every possible mapping from the query graph to the network that meets the associated symmetry-breaking conditions.

As it is mentioned above, the symmetry-breaking technique is a simple mechanism that precludes spending time finding a sub-graph more than once due to its symmetries.

[35] Omidi et al. [36] introduced a new algorithm for motif detection named MODA which is applicable for induced and non-induced NM discovery in undirected networks.

Although motif-centric algorithms also have problems in discovering all possible large size sub-graphs, but their ability to find small numbers of them is sometimes a significant property.

As a result, we can exploit the mapping set of a graph to determine the frequencies of its same order supergraphs simply in O(1) time without carrying out sub-graph isomorphism testing.

The algorithm starts ingeniously with minimally connected query graphs of size k and finds their mappings in the network via sub-graph isomorphism.

[37] This approach generates approximations; however, the results are almost stable in different executions since sub-graphs aggregate around highly connected nodes.

In 2010, Pedro Ribeiro and Fernando Silva proposed a novel data structure for storing a collection of sub-graphs, called a g-trie.

Taking advantage of common substructures in the sense that at a given time there is a partial isomorphic match for several different candidate sub-graphs.

The leading hypothesis is that the network motif were independently selected by evolutionary processes in a converging manner,[45][46] since the creation or elimination of regulatory interactions is fast on evolutionary time scale, relative to the rate at which genes change,[45][46][47] Furthermore, experiments on the dynamics generated by network motifs in living cells indicate that they have characteristic dynamical functions.

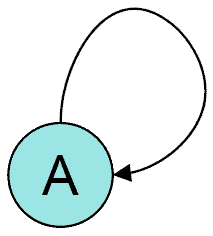

[50] The second function is increased stability of the auto-regulated gene product concentration against stochastic noise, thus reducing variations in protein levels between different cells.

The C1-FFL with an AND gate was shown to have a function of a 'sign-sensitive delay' element and a persistence detector both theoretically [56] and experimentally[58] with the arabinose system of E. coli.

The opposite behavior emerges in the case of a sum gate with fast response and delayed shut off as was demonstrated in the flagella system of E.

[59] De novo evolution of C1-FFLs in gene regulatory networks has been demonstrated computationally in response to selection to filter out an idealized short signal pulse, but for non-idealized noise, a dynamics-based system of feed-forward regulation with different topology was instead favored.

[63] Finally, expression units that incorporate incoherent feedforward control of the gene product provide adaptation to the amount of DNA template and can be superior to simple combinations of constitutive promoters.

[64] Feedforward regulation displayed better adaptation than negative feedback, and circuits based on RNA interference were the most robust to variation in DNA template amounts.

[64] De novo evolution of I1-FFLs in gene regulatory networks has been demonstrated computationally in response to selection to a generate a pulse, with I1-FFLs being more evolutionarily accessible, but not superior, relative to an alternative motif in which it is the output rather than the input that activates the repressor.

Kaplan et al.[69] has mapped the input functions of the sugar utilization genes in E. coli, showing diverse shapes.

An interesting generalization of the network-motifs, activity motifs are over occurring patterns that can be found when nodes and edges in the network are annotated with quantitative features.

For instance, when edges in a metabolic pathways are annotated with the magnitude or timing of the corresponding gene expression, some patterns are over occurring given the underlying network structure.