Biological network

As early as 1736 Leonhard Euler analyzed a real-world issue known as the Seven Bridges of Königsberg, which established the foundation of graph theory.

[4] In the 1980s, researchers started viewing DNA or genomes as the dynamic storage of a language system with precise computable finite states represented as a finite-state machine.

[5] Recent complex systems research has also suggested some far-reaching commonality in the organization of information in problems from biology, computer science, and physics.

[12] FunCoup and STRING are examples of such databases, where protein-protein interactions inferred from multiple evidences are gathered and made available for public usage.

[14] This observation suggests that the overall composition of the network (not simply interactions between protein pairs) is vital for an organism's overall functioning.

High-throughput measurement technologies, such as microarray, RNA-Seq, ChIP-chip, and ChIP-seq, enabled the accumulation of large-scale transcriptomics data, which could help in understanding the complex gene regulation patterns.

Cells break down the food and nutrients into small molecules necessary for cellular processing through a series of biochemical reactions.

[21][22] Single cell sequencing technologies allows the extraction of inter-cellular signaling, an example is NicheNet, which allows to modeling intercellular communication by linking ligands to target genes.

[24] For instance, small-world network properties have been demonstrated in connections between cortical regions of the primate brain[25] or during swallowing in humans.

[36] One of the most attractive features of the network paradigm would be that it provides a single conceptual framework in which the social organization of animals at all levels (individual, dyad, group, population) and for all types of interaction (aggressive, cooperative, sexual, etc.)

Researchers interested in social insects (e.g., ants and bees) have used network analyses better to understand the division of labor, task allocation, and foraging optimization within colonies.

[38][39][40] Other researchers are interested in how specific network properties at the group and/or population level can explain individual-level behaviors.

At the level of the individual, the patterning of social connections can be an important determinant of fitness, predicting both survival and reproductive success.

At the population level, network structure can influence the patterning of ecological and evolutionary processes, such as frequency-dependent selection and disease and information transmission.

For example, network analyses revealed subtle differences in the group dynamics of two related equid fission-fusion species, Grevy's zebra and onagers, living in variable environments; Grevy's zebras show distinct preferences in their association choices when they fission into smaller groups, whereas onagers do not.

[45] Finally, social network analysis can also reveal important fluctuations in animal behaviors across changing environments.

For example, network analyses in female chacma baboons (Papio hamadryas ursinus) revealed important dynamic changes across seasons that were previously unknown; instead of creating stable, long-lasting social bonds with friends, baboons were found to exhibit more variable relationships which were dependent on short-term contingencies related to group-level dynamics as well as environmental variability.

Research in this area is currently expanding very rapidly, especially since the broader development of animal-borne tags and computer vision can be used to automate the collection of social associations.

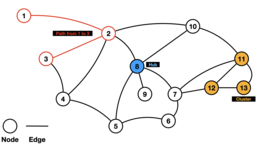

The figure illustrates strong connections between the center genomic windows as well as the edge loci at the beginning and end of the Hist1 region.

Formulation of these methods transcends disciplines and relies heavily on graph theory, computer science, and bioinformatics.

One of the types of measures that biologists utilize is correlation which specifically centers around the linear relationship between two variables.

[53] In 2005, Researchers at Harvard Medical School utilized centrality measures with the yeast protein interaction network.

[55] A food web of The Secaucus High School Marsh exemplifies the benefits of grouping as the relationships between nodes are far easier to analyze with well-made communities.

While the first graphic is hard to visualize, the second provides a better view of the pockets of highly connected feeding relationships that would be expected in a food web.

Scientists and graph theorists continuously discover new ways of sub sectioning networks and thus a plethora of different algorithms exist for creating these relationships.

[56] Like many other tools that biologists utilize to understand data with network models, every algorithm can provide its own unique insight and may vary widely on aspects such as accuracy or time complexity of calculation.

This allows for greater depth in choosing communities as the Louvain Method solely focuses on maximizing the modularity that was chosen.

The Leiden algorithm, while more complex than the Louvain Method, performs faster with better community detection and can be a valuable tool for identifying groups.