Neural crest

[5] Understanding the molecular mechanisms of neural crest formation is important for our knowledge of human disease because of its contributions to multiple cell lineages.

[1] He named the tissue "ganglionic crest," since its final destination was each lateral side of the neural tube, where it differentiated into spinal ganglia.

Modern cell labeling techniques such as rhodamine-lysinated dextran and the vital dye diI have also been developed to transiently mark neural crest lineages.

[6] The quail-chick marking system, devised by Nicole Le Douarin in 1969, was another instrumental technique used to track neural crest cells.

Researchers have demonstrated that the expression of dominate-negative Fgf receptor in ectoderm explants blocks neural crest induction when recombined with paraxial mesoderm.

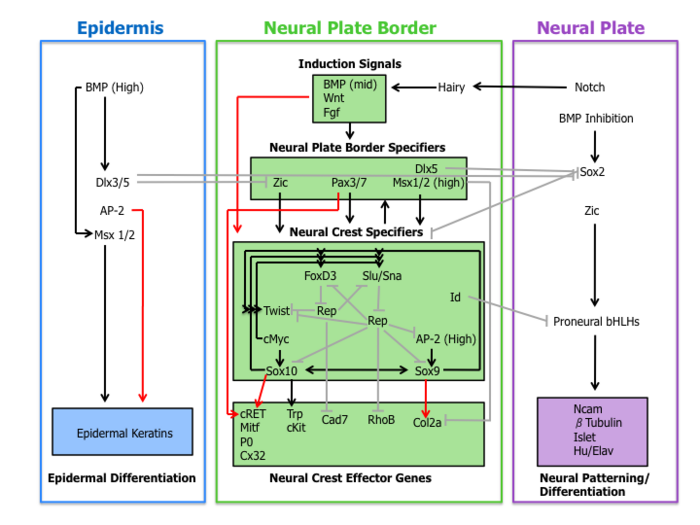

[11] The understanding of the role of BMP, Wnt, and Fgf pathways on neural crest specifier expression remains incomplete.

[16] Finally, neural crest specifiers turn on the expression of effector genes, which confer certain properties such as migration and multipotency.

Two neural crest effectors, Rho GTPases and cadherins, function in delamination by regulating cell morphology and adhesive properties.

[17] For migration to begin, neural crest cells must undergo a process called delamination that involves a full or partial epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT).

[17] These factors play a direct role in inducing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition by reducing expression of occludin and N-Cadherin in addition to promoting modification of NCAMs with polysialic acid residues to decrease adhesiveness.

[20] Additionally, neural crest cells begin expressing integrins that associate with extracellular matrix proteins, including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, during migration.

Instead of scaffolding on progenitor cells, neural crest migration is the result of repulsive guidance via EphB/EphrinB and semaphorin/neuropilin signaling, interactions with the extracellular matrix, and contact inhibition with one another.

When these two domains interact it causes receptor tyrosine phosphorylation, activation of rhoGTPases, and eventual cytoskeletal rearrangements within the crest cells inducing them to repel.

In chick embryos, semaphorin acts in the cephalic region to guide neural crest cells through the pharyngeal arches.

[17] Neural crest cells that migrate through the rostral half of somites differentiate into sensory and sympathetic neurons of the peripheral nervous system.

[20] Neurocristopathies result from the abnormal specification, migration, differentiation or death of neural crest cells throughout embryonic development.

In the case of piebaldism, the colorless skin areas are caused by a total absence of neural crest-derived pigment-producing melanocytes.

Also implicated in defects related to neural crest cell development and migration is Hirschsprung's disease, characterized by a lack of innervation in regions of the intestine.

Genes playing a role in the healthy migration of these neural crest cells to the gut include RET, GDNF, GFRα, EDN3, and EDNRB.

Severe FASD can impair neural crest migration, as evidenced by characteristic craniofacial abnormalities including short palpebral fissures, an elongated upper lip, and a smoothened philtrum.

Some defects observed are linked to the pharyngeal pouch system, which receives contribution from rostral migratory crest cells.

[33] Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS) results from the compromised development of the first and second pharyngeal arches during the early embryonic stage, which ultimately leads to mid and lower face abnormalities.

[21] These cells enter the pharyngeal pouches and arches where they contribute to the thymus, bones of the middle ear and jaw and the odontoblasts of the tooth primordia.

Also, this domain gives rise to regions of the heart such as the musculo-connective tissue of the large arteries, and part of the septum, which divides the pulmonary circulation from the aorta.

In their "New head" theory, Gans and Northcut argue that the presence of neural crest was the basis for vertebrate specific features, such as sensory ganglia and cranial skeleton.

For example, regulatory programs may be changed by the co-option of new upstream regulators or by the employment of new downstream gene targets, thus placing existing networks in a novel context.

[42] Ectomesenchyme (also known as mesectoderm):[43] odontoblasts, dental papillae, the chondrocranium (nasal capsule, Meckel's cartilage, scleral ossicles, quadrate, articular, hyoid and columella), tracheal and laryngeal cartilage, the dermatocranium (membranous bones), dorsal fins and the turtle plastron (lower vertebrates), pericytes and smooth muscle of branchial arteries and veins, tendons of ocular and masticatory muscles, connective tissue of head and neck glands (pituitary, salivary, lachrymal, thymus, thyroid) dermis and adipose tissue of calvaria, ventral neck and face Endocrine cells: chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, glomus cells type I/II.