Neutron star

It results from the supernova explosion of a massive star—combined with gravitational collapse—that compresses the core past white dwarf star density to that of atomic nuclei.

[3] Once formed, neutron stars no longer actively generate heat and cool over time, but they may still evolve further through collisions or accretion.

[18] Prior to this, indirect evidence for gravitational waves was inferred by studying the gravity radiated from the orbital decay of a different type of (unmerged) binary neutron system, the Hulse–Taylor pulsar.

Because it has only a tiny fraction of its parent's radius (sharply reducing its moment of inertia), a neutron star is formed with very high rotation speed and then, over a very long period, it slows.

[22] The neutron star's gravity accelerates infalling matter to tremendous speed, and tidal forces near the surface can cause spaghettification.

The extreme density means there is no way to replicate the material on earth in laboratories, which is how equations of state for other things like ideal gases are tested.

While the equation of state is only directly relating the density and pressure, it also leads to calculating observables like the speed of sound, mass, radius, and Love numbers.

Past numerical relativity simulations of binary neutron star mergers have found relationships between the equation of state and frequency dependent peaks of the gravitational wave signal that can be applied to LIGO detections.

[33] When nuclear physicists are trying to understand the likelihood of their equation of state, it is good to compare with these constraints to see if it predicts neutron stars of these masses and radii.

[25] However, the huge number of neutrinos it emits carries away so much energy that the temperature of an isolated neutron star falls within a few years to around 106 kelvin.

Variations in magnetic field strengths are most likely the main factor that allows different types of neutron stars to be distinguished by their spectra, and explains the periodicity of pulsars.

Current understanding of the structure of neutron stars is defined by existing mathematical models, but it might be possible to infer some details through studies of neutron-star oscillations.

[21] Current models indicate that matter at the surface of a neutron star is composed of ordinary atomic nuclei crushed into a solid lattice with a sea of electrons flowing through the gaps between them.

[53] It is also possible that heavy elements, such as iron, simply sink beneath the surface, leaving only light nuclei like helium and hydrogen.

When the density reaches a point where nuclei touch and subsequently merge, they form a fluid of neutrons with a sprinkle of electrons and protons.

The nuclei become increasingly small (gravity and pressure overwhelming the strong force) until the core is reached, by definition the point where mostly neutrons exist.

Pulsars' radiation is thought to be caused by particle acceleration near their magnetic poles, which need not be aligned with the rotational axis of the neutron star.

[63][64] This seems to be a characteristic of the X-ray sources known as Central Compact Objects in supernova remnants (CCOs in SNRs), which are thought to be young, radio-quiet isolated neutron stars.

The majority of neutron stars detected, including those identified in optical, X-ray, and gamma rays, also emit radio waves;[65] the Crab Pulsar produces electromagnetic emissions across the spectrum.

[68] A 2007 paper reported the detection of an X-ray burst oscillation, which provides an indirect measure of spin, of 1122 Hz from the neutron star XTE J1739-285,[69] suggesting 1122 rotations a second.

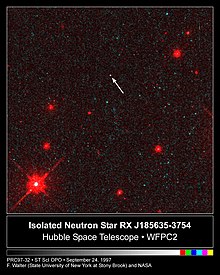

Another nearby neutron star that was detected transiting the backdrop of the constellation Ursa Minor has been nicknamed Calvera by its Canadian and American discoverers, after the villain in the 1960 film The Magnificent Seven.

The merger momentarily creates an environment of such extreme neutron flux that the r-process can occur; this—as opposed to supernova nucleosynthesis—may be responsible for the production of around half the isotopes in chemical elements beyond iron.

Pulsars can also strip the atmosphere off from a star, leaving a planetary-mass remnant, which may be understood as a chthonian planet or a stellar object depending on interpretation.

Pulsar planets receive little visible light, but massive amounts of ionizing radiation and high-energy stellar wind, which makes them rather hostile environments to life as presently understood.

In 1965, Antony Hewish and Samuel Okoye discovered "an unusual source of high radio brightness temperature in the Crab Nebula".

In 1967, Iosif Shklovsky examined the X-ray and optical observations of Scorpius X-1 and correctly concluded that the radiation comes from a neutron star at the stage of accretion.

In 1971, Riccardo Giacconi, Herbert Gursky, Ed Kellogg, R. Levinson, E. Schreier, and H. Tananbaum discovered 4.8 second pulsations in an X-ray source in the constellation Centaurus, Cen X-3.

In October 2018, astronomers reported that GRB 150101B, a gamma-ray burst event detected in 2015, may be directly related to the historic GW170817 and associated with the merger of two neutron stars.

[110] A 2020 study by University of Southampton PhD student Fabian Gittins suggested that surface irregularities ("mountains") may only be fractions of a millimeter tall (about 0.000003% of the neutron star's diameter), hundreds of times smaller than previously predicted, a result bearing implications for the non-detection of gravitational waves from spinning neutron stars.

[55][111][112] Using the JWST, astronomers have identified a neutron star within the remnants of the Supernova 1987A stellar explosion after seeking to do so for 37 years, according to a 23 February 2024 Science article.