Neo-Latin

The new style of Latin was adopted throughout Europe, first through the spread of urban education in Italy, and then the rise of the printing press and of early modern schooling.

Classical styles of writing, including approaches to rhetoric, poetical metres, and theatrical structures, were revived and applied to contemporary subject matter.

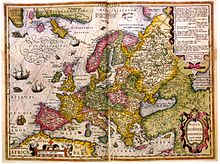

This in large part explains the continued use of Latin in Scandinavian countries and Russia – places that had never belonged to the Roman Empire – to disseminate knowledge until the early nineteenth century.

In the nineteenth century, education in Latin (and Greek) focused increasingly on reading and grammar, and mutated into the 'classics' as a topic, although it often still dominated the school curriculum, especially for students aiming for entry to university.

Reasons could include the rising belief during this period in the superiority of vernacular literatures, and the idea that only writing in one's first language could produce genuinely creative output, found in nationalism and Romanticism.

Classicists use the term "Neo-Latin" to describe the Latin that developed in Renaissance Italy as a result of renewed interest in classical civilization in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The spread of secular education, the acceptance of humanistic literary norms, and the wide availability of Latin texts following the invention of printing, mark the transition to a new era of scholarship at the end of the 15th century, but there was no simple, decisive break with medieval traditions.

[34] Prominent Neo-Latin writers who were admired for their style in this early period included Pontano, Petrarch, Salutati, Bruni, Ficino, Pico della Mirandola in Italy; the Spaniard Juan Luis Vives; and in northern Europe, the German Celtis.

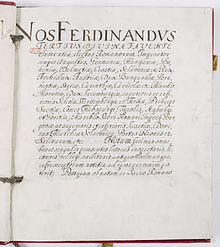

[41] The heyday of Neo-Latin was 1500–1700, when in the continuation of the Medieval Latin tradition, it served as the lingua franca of science, medicine, legal discourse, theology, education, and to some degree diplomacy in Europe.

At a higher level, Erasmus' Colloquia helped equip Latin speakers with urbane and polite phraseology, and means of discussing more philosophical topics.

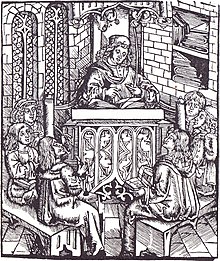

[46] Unlike medieval schools, however, Italian Renaissance methods focused on Classical models of Latin prose style, reviving texts from that period, such as Cicero's De Inventione or Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria.

As noted above, Jesuit schools fuelled a high standard of Latinity, and this was also supported by the growth of seminaries, as part of the Counter Reformation's attempts to revitalise Catholic institutions.

[64] Outputs included novels, poems, plays and occasional pieces, stretching across genres analogous to those found in vernacular writings of the period, such as tragedy, comedy, satire, history and political advice.

[67] At the time that many of these works were written, writers viewed their Latin output as perhaps we do high art; a particularly refined and lofty activity, for the most educated audiences.

In England, among typically unpublished scholarly works such as dissertations through the sixteenth century, written Latin improved in morphological accuracy, but sentence construction and idiom often reflected the vernacular.

As a rule, their judgement was very sound, and in most cases we will not as readers realize that we are dealing with neologisms ... A large number of them were probably on the lips of the ancient Romans, although they have not survived in the texts preserved to us.

Even among highly proficient Latin writers, sometimes spoken skills could be much lower, reflecting reticence for making mistakes in public, or simple lack of oral practice.

Increasingly, even as Latin's relevance and pupils' attainment in it diminished, the language became associated with class boundaries, as a passport to a certain kind of education and social cachet, which were denied to those who were unable to dedicate the time to studying it.

For instance, the Hanoverian king George I of Great Britain (reigned 1714–1727), who had no command of spoken English, communicated in Latin with his Prime Minister Robert Walpole.

In the early 18th century, French replaced Latin as the dominant diplomatic language, due to the commanding presence in Europe of the France of Louis XIV.

In grammar schools, however, study of Latin had declined, stopped or become tokenistic in the majority of cases at the point of the Taunton Commission's enquiry in 1864, a situation which it helped to reverse in the coming decades.

Latin had already lost its privileged role as the core subject of elementary instruction; and as education spread to the middle and lower classes, it tended to be dropped altogether.

Authors such as Arthur Rimbaud and Max Beerbohm wrote Latin verse, but these texts were either school exercises or occasional pieces.

Some of the last survivals of Neo-Latin to convey information appear in the use of Latin to cloak passages and expressions deemed too indecent to be read by children, the lower classes, or (most) women.

[f] Neo-Latin is also the source of the biological system of binomial nomenclature and classification of living organisms devised by Carl Linnaeus, although the rules of the ICZN allow the construction of names that deviate considerably from historical norms.

The Western family is characterized, inter alia, by having a front variant of the letter g before the vowels æ, e, i, œ, y and also pronouncing j in the same way (except in Italy).

The following table illustrates some of the variation of Neo-Latin consonants found in various countries of Europe, compared to the Classical Latin pronunciation of the 1st centuries BC to AD.

It was also found between vowels in the words ejus, hujus, cujus (earlier spelled eius, huius, cuius), and pronounced as a consonant; likewise in such forms as major and pejor.

The digraphs ae and oe were typically written using the ligatures æ and œ (e.g. Cæsar, pœna) except when part of a word in all capitals, such as in titles, chapter headings, or captions.

In practice, it was typically found on the vowel in the syllable immediately preceding a final clitic, particularly que "and", ve "or" and ne, a question marker; e.g. idémque "and the same (thing)".