History of Latin

Historical Latin came from the prehistoric language of the Latium region, specifically around the River Tiber, where Roman civilization first developed.

However, theories that the spoken and written languages were more or less different, separated by class or elite education, are now generally rejected.

It was the dominant language of European learning, literature and academia through the Middle Ages, and in the early modern period.

Latin's relevance as a widely used working language ended around 1800, although examples of its productive use extend well into that century, and in the cases of the Catholic Church and Classical studies, continue to the present day.

However, the Indo-European voiced aspirates bh, dh, gh, gwh are not maintained, becoming f, f, h, f respectively at the beginning of a word, but usually b, d, g, v elsewhere.

s between vowels becomes r, e.g. flōs "flower", gen. flōris; erō "I will be" vs. root es-; aurōra "dawn" < *ausōsā (cf.

Germanic *aust- > English "east", Vedic Sanskrit uṣā́s "dawn"); soror "sister" < *sozor < *swezōr < *swésōr (cf.

Of the original eight cases of Proto-Indo-European, Latin inherited six: nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, and ablative.

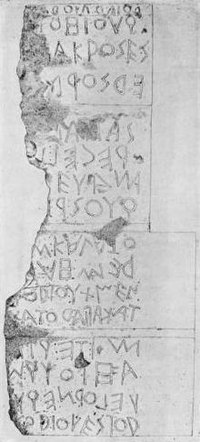

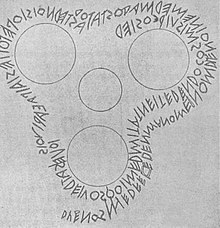

Classical Latin differs from Old Latin: the earliest inscriptional language and the earliest authors, such as Ennius, Plautus and others, in a number of ways; for example, the early -om and -os endings shifted into -um and -us ones, and some lexical differences also developed, such as the broadening of the meaning of words.

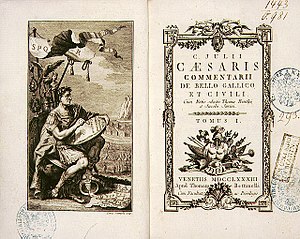

The Golden age of Latin literature is a period consisting roughly of the time from 75 BC to AD 14, covering the end of the Roman Republic and the reign of Augustus Caesar.

Because there are few phonetic transcriptions of the daily speech of these Latin speakers (to match, for example, the post-classical Appendix Probi) earlier forms of spoken Latin must be studied mainly by indirect methods, such as errors made in texts and transcripts.

The solecisms and non-Classical usages occasionally found in Late Latin texts also shed light on the spoken language, especially after 500 AD.

A windfall source lies in the chance finds of wax tablets such as those found at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall.

The Romance languages have more than 700 million native speakers worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Africa, as well as in many smaller regions scattered through the world.

[dubious – discuss] Between 200 BC and AD 100, the expansion of the Empire and the administrative and educational policies of Rome made Vulgar Latin the dominant vernacular language over a wide area which stretched from the Iberian Peninsula to the west coast of the Black Sea.

During the Empire's decline and after its collapse and fragmentation in the 5th century, spoken Latin began to evolve independently within each local area, and eventually diverged into dozens of distinct languages.

The overseas empires established by Spain, Portugal and France after the 15th century then spread these languages to other continents; about two thirds of all Romance speakers are now outside Europe.

Ecclesiastical Latin is not a single style: the term merely means the language promulgated at any time by the church.

They abandoned the use of the sequence and other accentual forms of meter, and sought instead to revive the Greek formats that were used in Latin poetry during the Roman period.

On the other hand, while humanist Latin was an elegant literary language, it became much harder to write books about law, medicine, science or contemporary politics in Latin while observing all of the humanists' norms of vocabulary purging and classical usage.

Humanist Latin continued to use neologisms, however; as a working language, it could not reply wholly on Classical vocabulary.

[14][15] Their attempts at literary work, especially poetry, can be viewed as having a strong element of pastiche; however, many modern Latinists, lacking a deep knowledge of the works of the period, are prone to see the obvious links with Classical period authors, without necessarily seeing the interplay that would have been understood at the time, or may dismiss genres such as poetry for patrons and official events as lacking merit, because these are so far from our mental model of creative spontenaity based on individual emotional inspiration.

Various kinds of contemporary Latin can be distinguished, including the use of single words in taxonomy, and the fuller ecclesiastical use in the Catholic Church.

Long vowels were largely unaffected in general except in final syllables, where they had a tendency to shorten.

Notes: Note: For the following examples, it helps to keep in mind the normal correspondences between PIE and certain other languages: In initial syllables, Latin generally preserves all of the simple vowels of Proto-Italic (see above):[18] Short vowel changes in initial syllables:[19] There are numerous examples where PIE *o appears to result in Latin a instead of expected o, mostly next to labial or labializing consonants.

Greek am/a, an/a, ar/ra, al/la; Germanic um, un, ur, ul; Sanskrit am/a, an/a, r̥, r̥; Lithuanian im̃, iñ, ir̃, il̃): The laryngeals *h₁, *h₂, *h₃ appear in Latin as a[n 4] when between consonants, as in most languages (but Greek e/a/o respectively, Sanskrit i): A sequence of syllabic resonant + laryngeal, when before a consonant, produced mā, nā, rā, lā (as also in Celtic, cf.

depending on the laryngeal; Germanic um, un, ur, ul; Sanskrit ā, ā, īr/ūr, īr/ūr; Lithuanian ím, ín, ír, íl): The Indo-European voiced aspirates bʰ, dʰ, gʰ, gʷʰ, which were probably breathy voiced stops, first devoiced in initial position (fortition), then fricatized in all positions, producing pairs of voiceless/voiced fricatives in Proto-Italic: f ~ β, θ ~ ð, χ ~ ɣ, χʷ ~ ɣʷ respectively.

In all Italic languages, the word-initial voiceless fricatives f, θ, and χʷ all merged to f, whereas χ debuccalized to h (except before a liquid where it became g); thus, in Latin, the normal outcome of initial PIE bʰ, dʰ, gʰ, gʷʰ is f, f, h, f, respectively.

This produces many alternations in Latin declension: Other examples: However, before another r, dissimilation occurred with sr [zr] becoming br (likely via an intermediate *ðr):[47] In groups of stop + /s/ before unvoiced consonants, the stop was lost:[48] Syncopated words like dexter (<*deksiteros) were not affected by this change.

/s/ was lost before voiced consonants, with compensatory lengthening:[49] Clusters involving /s/ were also lost before voiced consonants, also with compensatory lengthening:[50] Sequences of dl, ld, nl, ln, rl, ls became ll:[50] As shown by agellus this assimilation occurred after syncopation.