New Orleans Outfall Canals

[1] The 17th Street Canal extends 13,500 feet (4,100 m) north from Pump Station 6 to Lake Pontchartrain along the boundary of Orleans and Jefferson parishes.

[2] When Hurricane Katrina made landfall on August 29 along the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts, storm surge from the Gulf of Mexico flowed into Lake Pontchartrain.

Temporary pumps were later brought in to remove the water and drain the city, and the Orleans Metro sub-basin was officially declared dry on September 20, 2005.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers External Peer Review released June 1, 2007, the engineers responsible for the design of the outfall canal levees overestimated the soil strength, meaning that the soil strength used in the design calculations was greater than what actually existed under and near the levees during Hurricane Katrina.

In 2007, the United States Army Corps of Engineers published results from a year-long study intended primarily to determine the canal's "safe water level" for the 2007 hurricane season.

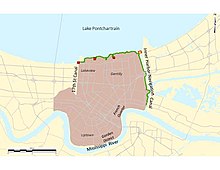

One of these sub-basins, referred to as “Orleans Metro” by the Corps of Engineers, today includes the most densely populated portion of New Orleans and is bound by Lake Pontchartrain to the north, the Mississippi River to the south, the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal to the east and the 17th Street Outfall Canal / Jefferson Parish line to the west (although a small portion of Jefferson Parish along the Mississippi River, known as Hoey’s Basin, is also included in this sub-basin).

[10] Fifty percent of New Orleans lies below sea level, so the city relies on manually operated pumps to remove rainwater from the land.

[11] New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, along the high ground adjacent to the Mississippi River (about 17 feet (5.2 m) above sea level).

However, the reduction in the groundwater table, as a result of the drainage and reclamation of swamps and marshland, produced significant land subsidence in the drained area.

In 1915 and again in 1947, devastating hurricanes struck the New Orleans area, causing millions of dollars in property damage and killing hundreds of residents.

The Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity area encompasses one large natural drainage basin that today includes the Orleans Metro sub-basin.

After seven years of planning, the New Orleans District produced an Interim Survey Report, which was transmitted by the Secretary of the Army to the U.S. Congress in November 1962.

As part of this original “Barrier Plan,” the existing levees along all three outfall canals were deemed adequate for hurricane protection purposes.

In September 1965, Hurricane Betsy struck the Louisiana coast near New Orleans, causing massive property damage and loss of life.

[15] Congress authorized the post-Hurricane-Betsy-modified Barrier Plan when the Flood Control Act of 1965 was passed, positioning the federal government to assume 70 percent of construction costs.

After authorization, the New Orleans District set out to develop detailed engineering plans, secure the required funding and real estate, and construct project features.

State governmental elected officials, congressional representatives and various local citizen and interest groups met the Barrier Plan with opposition.

Ultimately, however, the Corps did not return and, in 1980, concluded that an alternative option of higher levees providing hurricane protection was less costly, less damaging to the environment and more acceptable to local interests.

With the adoption of the High Level Plan, the New Orleans District could now move forward with providing hurricane and storm surge protection features along the lakefront and outfall canals.

Beginning in the late 1970s, the Corps’ New Orleans Board (OLB) began identifying and examining hurricane protection alternatives for the outfall canals.

There is no stated evidence in the project record that the corps felt that there were differences between the approaches in providing reliable surge protection (Woolley Shabman, 2–48).

As interior drainage was not part of the federal authorization for hurricane protection, the OLB and the Sewerage and Water Board would be responsible for any costs associated with pump installation at the mouths of the outfall canals.

With the dispute over hurricane protection solutions for the outfall canals seemingly resolved, the Corps began designing and constructing predominantly “I-wall”-type floodwalls on top of the levee crowns.

I-walls met the project goals of providing increased embankment heights within the limited existing rights-of-way with minimal disruption to the adjacent residential neighborhoods.

This authority superseded any previous legislation prior to Hurricane Katrina that prohibited the Corps from building closure structures at the mouths of the outfall canals.

[23] In the years since Hurricane Katrina, the Corps of Engineers has been constructing and bolstering 350 miles (560 km) of levees, floodwalls, barriers, gates and other structures as part of the Greater New Orleans Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS), which stretches across five parishes and includes much of the original Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity Basin, as well as the West Bank and Vicinity Basin on the West Bank of the Mississippi River.