Nilotic landscape

The production of nilotic landscapes as well as their iconography and interpretations depend on the provenance of the work and the culture in which it was produced, but most scenes on the whole affirm and celebrate the abundance of nature.

The annual flooding of the Nile river in Egypt was not only the source of the ancient civilization's food and crops, but also provided them with a dependable cyclical calendar.

Other nilotic landscapes, especially those outside of Egypt, include exotic, foreign animals, such as monkeys and crocodiles, and often fantastic creatures or monsters like griffins and sphinxes.

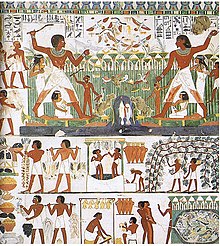

These scenes stress the elite character and importance of the deceased, who conquers nature and dominates the landscape, participating in activities reserved for the upper class.

[2] Artistically, the scenes are characterized by a sense of movement and liveliness not normally seen in most Egyptian works, which for centuries portrayed static, stoic figures and creatures.

River scenes suggesting the natural world and its lush vegetation begin to appear outside of Egypt contemporaneously with the 18th Dynasty, the first extant evidence coming from fresco fragments of the Minoans.

Attention is paid to detail and color with respect to plants and animals, but precisely drawn patterns seldom arise and the background and setting may be highly imaginative.

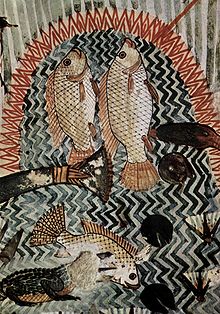

[5] This scene has been dubbed a “nilotic landscape” by archaeologists and art historians due to its inclusion of blue monkeys and papyrus in a riverine setting.

Unlike the two other fresco scenes in this room, the nilotic landscape is devoid of human figures and lacks narrative, focusing instead on the wildlife and environment and glorifying the natural world.

[7] A number of biblical subjects in art, such as the Finding of Moses, are set in Egypt, and Christian artists slowly evolved modest conventions for conveying the unfamiliar landscape.