Inanna

The cult of Inanna/Ishtar, which may have been associated with a variety of sexual rites, was continued by the East Semitic-speaking peoples (Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians) who succeeded and absorbed the Sumerians in the region.

Scholars believe that Inanna and Ishtar were originally separate, unrelated deities,[13] but were conflated with one another during the reign of Sargon of Akkad and came to be regarded as effectively the same goddess under two different names.

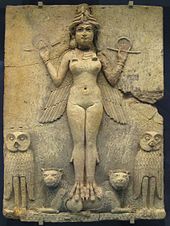

[22] Inanna has posed a problem for many scholars of ancient Sumer due to the fact that her sphere of power contained more distinct and contradictory aspects than that of any other deity.

[30] The female stands in front of Inanna's symbol of the two twisted reeds of the doorpost,[30] while the male figure holds a box and stack of bowls, the later cuneiform sign signifying the En, or high priest of the temple.

[31] Seal impressions from the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100–2900 BCE) show a fixed sequence of symbols representing various cities, including those of Ur, Larsa, Zabalam, Urum, Arina, and probably Kesh.

[32] A large number of similar seals have been discovered from phase I of the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BCE) at Ur, in a slightly different order, combined with the rosette symbol of Inanna.

[43] Joan Goodnick Westenholz proposed that a goddess identified by the name Nin-UM (reading and meaning uncertain), associated with Ishtaran in a zame hymn, was the original identity of Inanna of Zabalam.

[73] In the Biblical book of Jeremiah, the prophet condemns Judean female refugees for worshipping the Queen of Heaven (a syncretism of Ishtar and Asherah) by baking cakes with the goddess's image upon them and pouring libations to her (Jer.

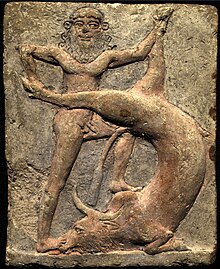

[118] Mesopotamian texts indicate that traits perceived as heroic (such as a king's ability to lead his troops and to triumph over enemies) and sexual prowess were regarded as interconnected.

[153] There is also similarly scarce evidence for the love goddess Nanaya being regarded as her daughter, but it is possible all of these instances merely refer to an epithet indicating closeness between the deities and were not a statement about actual parentage.

[167] In later periods Ishtar's name was sometimes used as a generic term ("goddess") in Babylonia, while a logographic writing of Inanna was used to spell the title Bēltu, leading to further conflations.

[214] These aspects were very diverse and the mes listed in the poem include abstract concepts such as Truth, Victory, and Counsel, technologies such as writing and weaving, and also social constructs such as law, priestly offices, kingship, and prostitution.

[17] The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative,[17] but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take.

[245] The rebellion of the mountain of Ebiḫ and its destruction by Inanna is also mentioned in the hymn Innin ša gura ("Mistress of the Great Heart"), which is ascribed to the high priestess En-ḫedu-ana.

[248] Inanna stands on top of a stool[248] and transforms Bilulu into "the waterskin that men carry in the desert",[251] forcing her to pour the funerary libations for Dumuzid.

[292][277] Despite Inanna's fate, and in contrast to the other individuals who were properly mourning her, Dumuzi is lavishly clothed and resting beneath a tree, or upon her throne, entertained by slave-girls.

[307] Ea creates an androgynous being called Asu-shu-namir and sends them to Ereshkigal, telling them to invoke "the name of the great gods" against her and to ask for the bag containing the waters of life.

Dina Katz, an authority on Sumerian afterlife beliefs and funerary customs, considers the narrative of Inanna's descent to be a combination of two distinct preexisting traditions rooted in broader context of Mesopotamian religion.

She considers it possible that the connection between the two parts of the narrative was meant to mirror some well attested healing rituals which required a symbolic substitute of the person being treated.

[105] Katz also notes that the Sumerian version of the myth is not concerned with matters of fertility, and points out any references to it (e.g. to nature being infertile while Ishtar is dead) were only added in later Akkadian translations;[313] so was the description of Tammuz's funeral.

[313] The purpose of these changes was likely to make the myth closer to cultic traditions linked to Tammuz, namely the annual mourning of his death followed by celebration of a temporary return.

[326][324] Later in the epic, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the Great Flood,[327] which was sent by the god Enlil to annihilate all life on earth because the humans, who were vastly overpopulated, made too much noise and prevented him from sleeping.

From the dirt of his fingernails he forms the powerful goddess Ṣaltum ("fight, quarrel"), whom he instructs to confront Ishtar disrespectfully and plague her day and night with her roar.

A myth about the childhood of the god Ishum, viewed as a son of Shamash, describes Ishtar seemingly temporarily taking care of him, and possibly expressing annoyance at that situation.

[344][345] Marina Warner (a literary critic rather than Assyriologist) claims that early Christians in the Middle East assimilated elements of Ishtar into the cult of the Virgin Mary.

[347] However, broad comparisons between Tammuz and other dying gods are rooted in the work of James George Frazer and are regarded as a relic of less rigorous early 20th century Assyriology by more recent publications.

[345] In the tenth century AD, an Arab traveler wrote that "All the Sabaeans of our time, those of Babylonia as well as those of Harran, lament and weep to this day over Tammuz at a festival which they, more particularly the women, hold in the month of the same name.

[379] Significantly influenced by Edward FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia,[379] Hamilton's characters dress more like nineteenth-century Turks than ancient Babylonians.

[388] Tikva Frymer-Kensky has argued that Inanna was a "marginal figure" in Sumerian religion who embodies the "socially unacceptable" archetype of the "undomesticated, unattached woman".

[388] Assyriologist Julia M. Asher-Greve, who specializes in the study of position of women in antiquity, criticizes Frymer-Kensky's studies of Mesopotamian religion as a whole, highlighting the problems with her focus on fertility, the small selection of sources her works relied on, her view that position of goddesses in the pantheon reflected that of ordinary women in society (so-called "mirror theory"), as well as the fact her works do not accurately reflect the complexity of changes of roles of goddesses in religions of ancient Mesopotamia.