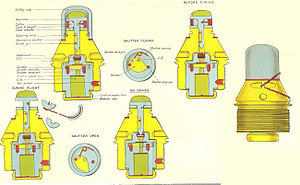

No. 106 fuze

British heavy artillery was expected to attack fortifications, requiring high-explosive shells to penetrate the target to some extent before exploding.

Experiences of trench warfare on the Western front in 1914–1916 indicated that British artillery was unable to reliably destroy barbed-wire barricades, which required shells to explode instantaneously on contact with the wire or ground surface: British high-explosive shells would penetrate the ground before exploding, rendering them useless for destroying surface targets.

101, 102 and 103 nose "graze" fuzes available in the field from August 1915 onwards[1] could explode a high-explosive shell very quickly on experiencing a major change in direction or velocity, but were not "instantaneous": there was still some delay in activation, and limited sensitivity: they could not detect contact with a frail object like barbed wire or soft ground surface.

[2] These graze and impact fuzes continued to be used as intended for medium and heavy artillery high-explosive shells.

The number 106 fuze drew on French technology to provide a mechanism for reliably detonating a high-explosive shell instantaneously when the nose made physical contact with the slightest object like a strand of barbed wire or the ground surface.

The steel hammer had a softer aluminium cap which absorbed the force of a glancing blow and prevented the spindle from bending or breaking, reducing the risk of misfire.

The fuze was first used experimentally in action in the later phases of the Battle of the Somme in late 1916, and entered service in early 1917.

[3][4] From then onwards British forces had a reliable means of detonating high-explosive shells on the ground surface without merely digging holes as they had previously.