Cardinal point (optics)

The paraxial approximation assumes that rays travel at shallow angles with respect to the optical axis, so that

The rear (or back) focal point of the system has the reverse property: rays that enter the system parallel to the optical axis are focused such that they pass through the rear focal point.

An object infinitely far from the optical system forms an image at the rear focal plane.

A diaphragm or "stop" at the rear focal plane of a lens can be used to filter rays by angle, since an aperture centred on the optical axis there will only pass rays that were emitted from the object at a sufficiently small angle from the optical axis.

Using a sufficiently small aperture in the rear focal plane will make the lens object-space telecentric.

The pixels in these sensors are more sensitive to rays that hit them straight on than to those that strike at an angle.

A lens that does not control the angle of incidence at the detector will produce pixel vignetting in the images.

In the more general case, the distance to the foci is the focal length multiplied by the index of refraction of the medium.

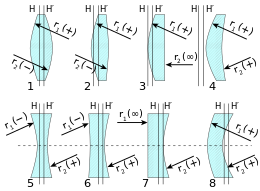

where f is the focal length of the lens, d is its thickness, and r1 and r2 are the radii of curvature of its surfaces.

The nodal points therefore do for angles what the principal planes do for transverse distance.

Gauss's original 1841 paper only discussed the main rays through the focal points.

A colleague, Johann Listing, was the first to describe the nodal points in 1845 to evaluate the human eye, where the image is in fluid.

[5] The cardinal points were all included in a single diagram as early as 1864 (Donders), with the object in air and the image in a different medium.

The nodal points characterize a ray that goes through the centre of a lens without any angular deviation.

This is a valuable addition in its own right to what has come to be called "Gaussian optics", and if the image was in fluid instead, then that same ray would refract into the new medium, as it does in the diagram to the right.

A ray through the nodal points has parallel input and output portions (blue).

A simple method to find the rear nodal point for a lens with air on one side and fluid on the other is to take the rear focal length f′ and divide it by the image medium index, which gives the effective focal length (EFL) of the lens.

The eye itself has a second special use of the nodal point that tends to be obscured by paraxial discussions.

The cornea and retina are highly curved, unlike most imaging systems, and the optical design of the eye has the property that a "direction line" that is parallel to the input rays can be used to find the magnification or to scale retinal locations.

This scaling property is well-known, very useful, and very simple: angles drawn with a ruler centred on the posterior pole of the lens on a cross-section of the eye can approximately scale the retina over more than an entire hemisphere.

It is only in the 2000s that the limitations of this approximation have become apparent, with an exploration into why some intraocular lens (IOL) patients see dark shadows in the far periphery (negative dysphotopsia, which is probably due to the IOL being much smaller than the natural lens.

In the figure at right,[8] the points A and B are where parallel lines of radii of curvature R1 and R2 meet the lens surfaces.

A better choice of the point about which to pivot a camera for panoramic photography can be shown to be the centre of the system's entrance pupil.

They are important primarily because they are physically measurable parameters for the optical element positions, and so the positions of the cardinal points of the optical system must be known with respect to the surface vertices to describe the system.

This term also applies to corresponding pairs of object and image points and planes.

An optical system is rotationally symmetric if its imaging properties are unchanged by any rotation about some axis.

Rotational symmetry greatly simplifies the analysis of optical systems, which otherwise must be analyzed in three dimensions.

Rotational symmetry allows the system to be analyzed by considering only rays confined to a single transverse plane containing the optical axis.

Rays are real when they are in the part of the optical system to which they apply, and are virtual elsewhere.

Geometrical similarity implies the image is a scale model of the object.