Geometrical optics

The ray in geometrical optics is an abstraction useful for approximating the paths along which light propagates under certain circumstances.

This simplification is useful in practice; it is an excellent approximation when the wavelength is small compared to the size of structures with which the light interacts.

The techniques are particularly useful in describing geometrical aspects of imaging, including optical aberrations.

The mathematical behavior then becomes linear, allowing optical components and systems to be described by simple matrices.

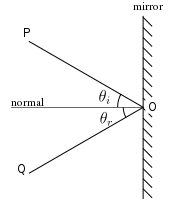

This allows for production of reflected images that can be associated with an actual (real) or extrapolated (virtual) location in space.

The law also implies that mirror images are parity inverted, which is perceived as a left-right inversion.

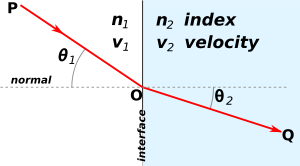

In such situations, Snell's Law describes the resulting deflection of the light ray:

are the angles between the normal (to the interface) and the incident and refracted waves, respectively.

This phenomenon is also associated with a changing speed of light as seen from the definition of index of refraction provided above which implies:

[3] Various consequences of Snell's Law include the fact that for light rays traveling from a material with a high index of refraction to a material with a low index of refraction, it is possible for the interaction with the interface to result in zero transmission.

This phenomenon is called total internal reflection and allows for fiber optics technology.

The discovery of this phenomenon when passing light through a prism is famously attributed to Isaac Newton.

[3] Some media have an index of refraction which varies gradually with position and, thus, light rays curve through the medium rather than travel in straight lines.

This effect is what is responsible for mirages seen on hot days where the changing index of refraction of the air causes the light rays to bend creating the appearance of specular reflections in the distance (as if on the surface of a pool of water).

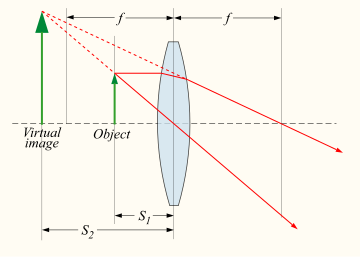

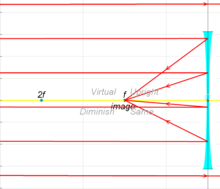

[4] A device which produces converging or diverging light rays due to refraction is known as a lens.

Thin lenses produce focal points on either side that can be modeled using the lensmaker's equation.

The detailed prediction of how images are produced by these lenses can be made using ray-tracing similar to curved mirrors.

Similarly to curved mirrors, thin lenses follow a simple equation that determines the location of the images given a particular focal length (

[3] Lenses suffer from aberrations that distort images and focal points.

[3] As a mathematical study, geometrical optics emerges as a short-wavelength limit for solutions to hyperbolic partial differential equations (Sommerfeld–Runge method) or as a property of propagation of field discontinuities according to Maxwell's equations (Luneburg method).

enters the scene due to highly oscillatory initial conditions.

Thus, when initial conditions oscillate much faster than the coefficients of the differential equation, solutions will be highly oscillatory, and transported along rays.

The method of obtaining equations of geometrical optics by taking the limit of zero wavelength was first described by Arnold Sommerfeld and J. Runge in 1911.

[9] Substituting the series into the equation and collecting terms of different orders, one finds

[10] It does not restrict the electromagnetic field to have a special form required by the Sommerfeld-Runge method which assumes the amplitude

An example of such surface of discontinuity is the initial wave front emanating from a source that starts radiating at a certain instant of time.

[11] The proof of Luneburg's theorem is based on investigating how Maxwell's equations govern the propagation of discontinuities of solutions.

) and the square brackets denote the difference in values on both sides of the discontinuity surface (set up according to an arbitrary but fixed convention, e.g. the gradient

It's now easy to show that as they propagate through a continuous medium, the discontinuity surfaces obey the eikonal equation.

In four-vector notation used in special relativity, the wave equation can be written as