Nodena phase

They practiced extensive maize agriculture and artificial cranial deformation and were members of a continent wide trade and religious network known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, which brought chert, whelk shells, and other exotic goods to the area.

The Spanish Hernando de Soto Expedition is believed to have visited several sites in the Nodena phase in the early 1540s, which is usually identified as the Province of Pacaha.

It was buff colored, contains large fragments of ground mussel shell as a tempering agent, and is not as smooth and polished as other varieties.

Shapes and decoration were varied in the mortuary pottery, from brightly colored abstract spiral designs, to elaborate effigy vessels depicting human heads, animals, and hunters and their prey.

[1] Nodena phase peoples traded with other groups to the west and northwest in the Crowley's Ridge and Ozark Highlands areas for usable stone to make tools.

Chert, basalt, and sandstone were turned into a variety of tools such as celts, chisels, adzes, abraders, hammerstones, hoes, drillbits, mortar and pestles, spear points, and arrow heads.

[11] The people of Nodena were intensely involved in maize agriculture, as well as other food crops originating in the Americas, such as beans, squash, sunflowers and gourds.

[12] The hunting of whitetail deer, squirrel, rabbit, turkey, and mallard was practiced as well as fishing for alligator gar, catfish, drum, and mussels.

But by the time of later European contact in the 1670s and the beginning of the historic period, the area was occupied by the Dhegiha Siouan speaking Quapaw.

The archaeological and ethnohistorical records suggest that the groups were rival or politically allied polities, with no neutral parties, engaged in internecine conquest warfare.

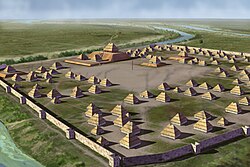

The presence of palisades, earthen embankments and moats and the absence of isolated single-family dwellings and smaller hamlets among the local phases suggests such a state of endemic warfare existed.

The Casqui who had followed de Soto proceeded to sack the village, desecrate the temple and the remains of the Pacaha honored dead, and steal everything they could.

The Casqui received advance warning of the planned attack and decided to return the looted items and issue an apology in order to stave off retribution from the combined Spanish and Pacaha force.

By the time of the next documented European presence in the area in 1673 by the Marquette and Jolliet expedition, the region was populated sparsely by the Quapaw.

The introduction of European diseases such as smallpox and measles[14] and the upsetting of the local balance of power by the Spaniards is thought to have contributed to the depopulation of the region described by the de Soto expedition as the most populous they had seen in La Florida.