Noether's theorem

[citation needed] As an illustration, if a physical system behaves the same regardless of how it is oriented in space (that is, it's invariant), its Lagrangian is symmetric under continuous rotation: from this symmetry, Noether's theorem dictates that the angular momentum of the system be conserved, as a consequence of its laws of motion.

[2]: 126 The physical system itself need not be symmetric; a jagged asteroid tumbling in space conserves angular momentum despite its asymmetry.

As another example, if a physical process exhibits the same outcomes regardless of place or time, then its Lagrangian is symmetric under continuous translations in space and time respectively: by Noether's theorem, these symmetries account for the conservation laws of linear momentum and energy within this system, respectively.

[3]: 23 [4]: 261 Noether's theorem is important, both because of the insight it gives into conservation laws, and also as a practical calculational tool.

It allows investigators to determine the conserved quantities (invariants) from the observed symmetries of a physical system.

Conversely, it allows researchers to consider whole classes of hypothetical Lagrangians with given invariants, to describe a physical system.

Due to Noether's theorem, the properties of these Lagrangians provide further criteria to understand the implications and judge the fitness of the new theory.

[5] All fine technical points aside, Noether's theorem can be stated informally as: If a system has a continuous symmetry property, then there are corresponding quantities whose values are conserved in time.

[6]A more sophisticated version of the theorem involving fields states that: To every continuous symmetry generated by local actions there corresponds a conserved current and vice versa.The word "symmetry" in the above statement refers more precisely to the covariance of the form that a physical law takes with respect to a one-dimensional Lie group of transformations satisfying certain technical criteria.

The formal proof of the theorem utilizes the condition of invariance to derive an expression for a current associated with a conserved physical quantity.

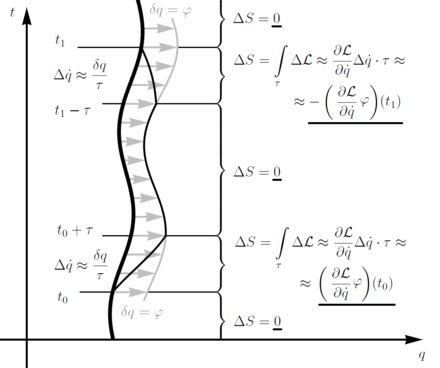

In the context of gravitation, Felix Klein's statement of Noether's theorem for action I stipulates for the invariants:[7] If an integral I is invariant under a continuous group Gρ with ρ parameters, then ρ linearly independent combinations of the Lagrangian expressions are divergences.The main idea behind Noether's theorem is most easily illustrated by a system with one coordinate

A conservation law states that some quantity X in the mathematical description of a system's evolution remains constant throughout its motion – it is an invariant.

Aside from insights that such constants of motion give into the nature of a system, they are a useful calculational tool; for example, an approximate solution can be corrected by finding the nearest state that satisfies the suitable conservation laws.

The earliest constants of motion discovered were momentum and kinetic energy, which were proposed in the 17th century by René Descartes and Gottfried Leibniz on the basis of collision experiments, and refined by subsequent researchers.

The local conservation of non-gravitational linear momentum and energy in a free-falling reference frame is expressed by the vanishing of the covariant divergence of the stress–energy tensor.

Another important conserved quantity, discovered in studies of the celestial mechanics of astronomical bodies, is the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector.

Several alternative methods for finding conserved quantities were developed in the 19th century, especially by William Rowan Hamilton.

Emmy Noether's work on the invariance theorem began in 1915 when she was helping Felix Klein and David Hilbert with their work related to Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity[8]: 31 By March 1918 she had most of the key ideas for the paper which would be published later in the year.

One can assume that the Lagrangian L defined above is invariant under small perturbations (warpings) of the time variable t and the generalized coordinates q.

For generality, assume there are (say) N such symmetry transformations of the action, i.e. transformations leaving the action unchanged; labelled by an index r = 1, 2, 3, ..., N. Then the resultant perturbation can be written as a linear sum of the individual types of perturbations, where εr are infinitesimal parameter coefficients corresponding to each: For translations, Qr is a constant with units of length; for rotations, it is an expression linear in the components of q, and the parameters make up an angle.

In the limit when the phase θ becomes infinitesimally small, δθ, it may be taken as the parameter ε, while the Ψ are equal to iψ and −iψ*, respectively.

and so the conserved quantity simplifies to To avoid excessive complication of the formulas, this derivation assumed that the flow does not change as time passes.

Noether's theorem begins with the assumption that a specific transformation of the coordinates and field variables does not change the action, which is defined as the integral of the Lagrangian density over the given region of spacetime.

Since ξ is a dummy variable of integration, and since the change in the boundary Ω is infinitesimal by assumption, the two integrals may be combined using the four-dimensional version of the divergence theorem into the following form The difference in Lagrangians can be written to first-order in the infinitesimal variations as However, because the variations are defined at the same point as described above, the variation and the derivative can be done in reverse order; they commute Using the Euler–Lagrange field equations the difference in Lagrangians can be written neatly as Thus, the change in the action can be written as Since this holds for any region Ω, the integrand must be zero For any combination of the various symmetry transformations, the perturbation can be written where

, These equations imply that the field variation taken at one point equals Differentiating the above divergence with respect to ε at ε = 0 and changing the sign yields the conservation law where the conserved current equals Suppose we have an n-dimensional oriented Riemannian manifold, M and a target manifold T. Let

Let ε be any arbitrary smooth function of the spacetime (or time) manifold such that the closure of its support is disjoint from the boundary.

More generally, if the Lagrangian depends on higher derivatives, then Looking at the specific case of a Newtonian particle of mass m, coordinate x, moving under the influence of a potential V, coordinatized by time t. The action, S, is: The first term in the brackets is the kinetic energy of the particle, while the second is its potential energy.

The coordinate x has an explicit dependence on time, whilst V does not; consequently: so we can set Then, The right hand side is the energy, and Noether's theorem states that

Application of Noether's theorem allows physicists to gain powerful insights into any general theory in physics, by just analyzing the various transformations that would make the form of the laws involved invariant.

For example: In quantum field theory, the analog to Noether's theorem, the Ward–Takahashi identity, yields further conservation laws, such as the conservation of electric charge from the invariance with respect to a change in the phase factor of the complex field of the charged particle and the associated gauge of the electric potential and vector potential.