Nondualism

Through practices like meditation and self-inquiry, practitioners aim to bypass the limitations of conceptual understanding and directly apprehend the interconnectedness that transcends superficial distinctions.

The oldest surviving manuscript on Advaita Vedanta is by Gauḍapāda (6th century CE),[49] who has traditionally been regarded as the teacher of Govinda bhagavatpāda and the grandteacher of Adi Shankara.

[74][75] Eliot Deutsch and Rohit Dalvi state: In any event a close relationship between the Mahayana schools and Vedanta did exist, with the latter borrowing some of the dialectical techniques, if not the specific doctrines, of the former.

[90] Dasgupta and Mohanta note that Buddhism and Shankara's Advaita Vedanta are not opposing systems, but "different phases of development of the same non-dualistic metaphysics from the Upanishadic period to the time of Sankara".

Vedanta Desika defines Vishishtadvaita using the statement: Asesha Chit-Achit Prakaaram Brahmaikameva Tatvam – "Brahman, as qualified by the sentient and insentient modes (or attributes), is the only reality."

[94] His reinterpretation was, and is, very successful, creating a new understanding and appreciation of Hinduism within and outside India,[94] and was the principal reason for the enthusiastic reception of yoga, transcendental meditation and other forms of Indian spiritual self-improvement in the West.

[97] Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), the founder of the Brahmo Samaj, had a strong sympathy for the Unitarians,[98] who were closely connected to the Transcendentalists, who in turn were interested in and influenced by Indian religions early on.

[101] Debendranath Tagore brought this "neo-Hinduism" closer in line with western esotericism, a development which was furthered by Keshab Chandra Sen,[102] who was also influenced by transcendentalism, which emphasised personal religious experience over mere reasoning and theology.

[109][note 7] According to Anil Sooklal, Vivekananda's neo-Advaita "reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism":[111] The Neo-Vedanta is also Advaitic inasmuch as it holds that Brahman, the Ultimate Reality, is one without a second, ekamevadvitiyam.

[141][142] Stanislaw Schayer, a Polish scholar, argued in the 1930s that the Nikayas preserve elements of an archaic form of Buddhism which is close to Brahmanical beliefs,[144][145][146][147] and survived in the Mahayana tradition.

[168][167] According to Kameshwar Nath Mishra, one connotation of advaya in Indic Sanskrit Buddhist texts is that it refers to the middle way between two opposite extremes (such as eternalism and annihilationism), and thus it is "not two".

These extremes which must be avoided in order to understand ultimate reality are described by various characters in the text, and include: Birth and extinction, 'I' and 'Mine', Perception and non-perception, defilement and purity, good and not-good, created and uncreated, worldly and unworldly, samsara and nirvana, enlightenment and ignorance, form and emptiness and so on.

[170] The final character to attempt to describe ultimate reality is the bodhisattva Manjushri, who states: It is in all beings wordless, speechless, shows no signs, is not possible of cognizance, and is above all questioning and answering.

[171] Vimalakīrti responds to this statement by maintaining completely silent, therefore expressing that the nature of ultimate reality is ineffable (anabhilāpyatva) and inconceivable (acintyatā), beyond verbal designation (prapañca) or thought constructs (vikalpa).

[173][9] The concept of nonduality is also important in the other major Indian Mahayana tradition, the Yogacara school, where it is seen as the absence of duality between the perceiving subject (or "grasper") and the object (or "grasped").

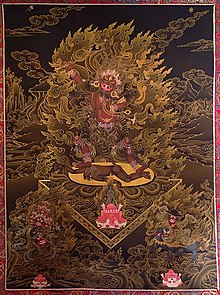

[191] In the Mahayana tradition of Yogācāra (Skt; "yoga practice"), adyava (Tibetan: gnyis med) refers to overcoming the conceptual and perceptual dichotomies of cognizer and cognized, or subject and object.

According to Mark Siderits the main idea of this doctrine is that we are only ever aware of mental images or impressions which manifest themselves as external objects, but "there is actually no such thing outside the mind.

According to Dan Lusthaus, this transformation which characterizes awakening is a "radical psycho-cognitive change" and a removal of false "interpretive projections" on reality (such as ideas of a self, external objects, etc.).

[208]This refers to the Yogācāra teaching that even though a Buddha has entered nirvana, they do no "abide" in some quiescent state separate from the world but continue to give rise to extensive activity on behalf of others.

[217] Buddhist Tantras also promote certain practices which are antinomian, such as sexual rites or the consumption of disgusting or repulsive substances (the "five ambrosias", feces, urine, blood, semen, and marrow.).

As Chinese Buddhism continued to develop in new innovative directions, it gave rise to new traditions like Tiantai and Chan (Zen), which also upheld their own unique teachings on non-duality.

The continuous pondering of the break-through kōan (shokan[233]) or Hua Tou, "word head",[234] leads to kensho, an initial insight into "seeing the (Buddha-)nature".

This trajectory of initial insight followed by a gradual deepening and ripening is expressed by Linji Yixuan in his Three Mysterious Gates, the Four Ways of Knowing of Hakuin,[246] the Five Ranks, and the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures[247] which detail the steps on the Path.

[266] The statements are:[264] Many newer, contemporary Sikhs have suggested that human souls and the monotheistic God are two different realities (dualism),[267] distinguishing it from the monistic and various shades of nondualistic philosophies of other Indian religions.

This holistic approach to life, characterized by spontaneous and unforced action, aligns with the essence of nondualism, emphasizing interconnectedness, oneness, and the dissolution of dualistic boundaries.

[274] The concept of Yin and Yang, often mistakenly conceived of as a symbol of dualism, is actually meant to convey the notion that all apparent opposites are complementary parts of a non-dual whole.

[286] Thomism, though not non-dual in the ordinary sense, considers the unity of God so absolute that even the duality of subject and predicate, to describe him, can be true only by analogy.

[307] Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite.

[294]The idea of a common essence has been questioned by Yandell, who discerns various "religious experiences" and their corresponding doctrinal settings, which differ in structure and phenomenological content, and in the "evidential value" they present.

[327] Gamma & Metzinger (2021) present twelve factors in their phenomenological analysis of pure awareness experienced by meditators, including luminosity; emptiness and non-egoic self-awareness; and witness-consciousness.