Non-uniform rational B-spline

It offers great flexibility and precision for handling both analytic (defined by common mathematical formulae) and modeled shapes.

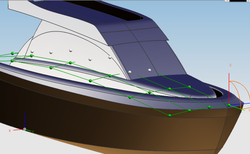

NURBS curves are commonly used in computer-aided design (CAD), manufacturing (CAM), and engineering (CAE).

Tools for creating and editing NURBS surfaces are found in various 3D graphics, rendering,[1] and animation software packages.

In a compact form, NURBS surfaces can represent simple geometrical shapes.

Depending on the type of user interface, the editing of NURBS curves and surfaces can be via their control points (similar to Bézier curves) or via higher level tools such as spline modeling and hierarchical editing.

Although such curves could be drawn freehand at the drafting board, shipbuilders often needed a life-size version which could not be done by hand.

Such large drawings were done with the help of flexible strips of wood, called splines.

[4] As computers were introduced into the design process, the physical properties of such splines were investigated so that they could be modelled with mathematical precision and reproduced where needed.

Pioneering work was done in France by Renault engineer Pierre Bézier, and Citroën's physicist and mathematician Paul de Casteljau.

Real-time, interactive rendering of NURBS curves and surfaces was first made commercially available on Silicon Graphics workstations in 1989.

[5] Note that the (partial) derivatives of curves and surfaces are vectors that have a direction and a magnitude; both should be equal.

Highlights and reflections can reveal the perfect smoothing, which is otherwise practically impossible to achieve without NURBS surfaces that have at least G² continuity.

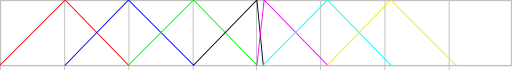

A NURBS curve is defined by its order, a set of weighted control points, and a knot vector.

[8]) By using a two-dimensional grid of control points, NURBS surfaces including planar patches and sections of spheres can be created.

Fifth- and sixth-order curves are sometimes useful, especially for obtaining continuous higher order derivatives, but curves of higher orders are practically never used because they lead to internal numerical problems and tend to require disproportionately large calculation times.

For a curve of degree d, the weight of any control point is only nonzero in d+1 intervals of the parameter space.

Note that within the interval the polynomial nature of the basis functions and the linearity of the construction make the curve perfectly smooth, so it is only at the knots that discontinuity can arise.

In many applications the fact that a single control point only influences those intervals where it is active is a highly desirable property, known as local support.

In particular, it adds conic sections like circles and ellipses to the set of curves that can be represented exactly.

Three-dimensional control points are used abundantly in 3D modeling, where they are used in the everyday meaning of the word 'point', a location in 3D space.

These curves share their degree and the number of control points, and span one dimension of the parameter space.

By interpolating these control vectors over the other dimension of the parameter space, a continuous set of curves is obtained, defining the surface.

The knot vector is a sequence of parameter values that determines where and how the control points affect the NURBS curve.

By changing the knot span lengths, more sample points can be used in regions where the curvature is high.

The knot span lengths then translate into velocity and acceleration, which are essential to get right to prevent damage to the robot arm or its environment.

Again by induction, it can be proved that the sum of the basis functions for a particular value of the parameter is unity.

On that knot span, the peak in the quadratic basis function is more distinct, reaching almost one.

In the geometrical interpretation, this means that the curve approaches the corresponding control point closely.

The process is used to clean up after an interactive session in which control points may have been added manually, or after importing a curve from a different representation, where a straightforward conversion process leads to redundant control points.

This would be impossible, since the x coordinate of the circle would provide an exact rational polynomial expression for