Vernacular

Regardless of any such stigma, all nonstandard dialects are full-fledged varieties of language with their own consistent grammatical structure, sound system, body of vocabulary, etc.

According to another definition, a vernacular is a language that has not developed a standard variety, undergone codification, or established a literary tradition.

The vernacular is contrasted with higher-prestige forms of language, such as national, literary, liturgical or scientific idiom, or a lingua franca, used to facilitate communication across a large area.

As a border case, a nonstandard dialect may even have its own written form, though it could then be assumed that the orthography is unstable, inconsistent, or unsanctioned by powerful institutions, like that of government or education.

In 1688, James Howell wrote: Concerning Italy, doubtless there were divers before the Latin did spread all over that Country; the Calabrian, and Apulian spoke Greek, whereof some Relics are to be found to this day; but it was an adventitious, no Mother-Language to them: 'tis confess'd that Latium it self, and all the Territories about Rome, had the Latin for its maternal and common first vernacular Tongue; but Tuscany and Liguria had others quite discrepant, viz.

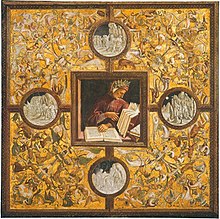

The Divina Commedia, the Cantar de Mio Cid, and The Song of Roland are examples of early vernacular literature in Italian, Spanish, and French, respectively.

With the rise of the bhakti movement from the 12th century onwards, religious works were created in other languages: Hindi, Kannada, Telugu and many others.

The non-standard varieties thus defined are dialects, which are to be identified as complexes of factors: "social class, region, ethnicity, situation, and so forth".

[21] However, in 1559, John III van de Werve, Lord of Hovorst published his grammar Den schat der Duytsscher Talen in Dutch; Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert (Eenen nieuwen ABC of Materi-boeck) followed five years after, in 1564.

The Latinizing tendency changed course, with a joint publication, in 1584 by De Eglantier and the rhetoric society of Amsterdam; this was to be the first comprehensive Dutch grammar, Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkunst/ ófte Vant spellen ende eyghenscap des Nederduitschen taals.

The British Isles, although geographically limited, have always supported populations of widely-varied dialects, as well as a few different languages; some examples of languages and regional accents (and/or dialects) within Great Britain include Scotland (Scottish Gaelic), Northumbria, Yorkshire, Wales (Welsh), the Isle of Man (Manx), Devon, and Cornwall (Cornish).

The first English grammars were written in Latin, with some in French,[24] after a general plea for mother-tongue education in England: The first part of the elementary, published in 1582, by Richard Mulcaster.

Other grammars in English followed rapidly; Paul Greaves' Grammatica Anglicana (1594), Alexander Hume's Orthographie and Congruitie of the Britain Tongue (1617), and many others.

[26] Over the succeeding decades, many literary figures turned a hand to grammar in English; Alexander Gill, Ben Jonson, Joshua Poole, John Wallis, Jeremiah Wharton, James Howell, Thomas Lye, Christopher Cooper, William Lily, John Colet and more, all leading to the massive dictionary of Samuel Johnson.

Some of the numerous 16th-century surviving grammars are: The development of a standard German was impeded by political disunity and strong local traditions until the invention of printing made possible a "High German-based book language".

Religious leaders wished to create a sacred language for Protestantism that would be parallel to the use of Latin for the Roman Catholic Church.

With so many linguists moving in the same direction, a standard German (hochdeutsche Schriftsprache) did evolve without the assistance of a language academy.

Latin prevailed as a lingua franca until the 17th century, when grammarians began to debate the creation of an ideal language.

Before 1550 as a conventional date, "supraregional compromises" were used in printed works, such as the one published by Valentin Ickelsamer (Ein Teutsche Grammatica) 1534.

By the time of his work of 1663, ausführliche Arbeit von der teutschen Haubt-Sprache, the standard language was well established.

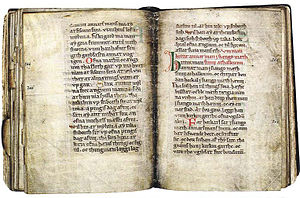

Auraicept na n-Éces is a grammar of the Irish language which is thought to date back as far as the 7th century: the earliest surviving manuscripts are 12th-century.

In it Alberti sought to demonstrate that the vernacular – here Tuscan, known today as modern Italian – was every bit as structured as Latin.

Known as the Leys d'amor and written by Guilhèm Molinièr, an advocate of Toulouse, it was published in order to codify the use of the Occitan language in poetry competitions organized by the company of the Gai Saber in both grammar and rhetorical ways.

Books 1–4 describe the Spanish language grammatically, in order to facilitate the study of Latin for its Spanish-speaking readers.

The Grammar Books of the Master-poets (Welsh: Gramadegau'r Penceirddiaid) are considered to have been composed in the early fourteenth century, and are present in manuscripts from soon after.

[37] As a result of this political instability no standard Dutch was defined (even though much in demand and recommended as an ideal) until after World War II.

[citation needed] No language academy was ever established or espoused by any government past or present in the English-speaking world.

After numerous dictionaries and glossaries of a less-than-comprehensive nature came a thesaurus that attempted to include all German, Kaspar Stieler's Der Teutschen Sprache Stammbaum und Fortwachs oder Teutschen Sprachschatz (1691), and finally the first codification of written German,[41] Johann Christoph Adelung's Versuch eines vollständigen grammatisch-kritischen Wörterbuches Der Hochdeutschen Mundart (1774–1786).

The term "vernacular" may also be applied metaphorically to any cultural product of the lower, common orders of society that is relatively uninfluenced by the ideas and ideals of the educated élite.

The historian Guy Beiner has developed the study of "vernacular historiography" as a more sophisticated conceptualization of folk history.