History of Ireland (1169–1536)

This latter development caused consternation to King Henry II of England, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland.

The relevant text reads: "There is indeed no doubt, as thy Highness doth also acknowledge, that Ireland and all other islands which Christ the Sun of Righteousness has illumined, and which have received the doctrines of the Christian faith, belong to the jurisdiction of St. Peter and of the holy Roman Church".

References to Laudabiliter become more frequent in the later Tudor period when the researches of the renaissance humanist scholars cast doubt on the historicity of the Donation of Constantine.

However, with both Diarmaid and Strongbow dead (in 1171 and 1176), Henry back in England and Ruaidhrí unable to curb his nominal vassals, within two years it was not worth the vellum it was inscribed upon.

[5] Normans altered Gaelic society with efficient land use, introducing feudalism to the existing native tribal-dynastic crop-sharing system.

Feudalism never caught on in large parts of Ireland, but it was an attempt to introduce cash payments into farming, which was entirely based on barter.

Many Irish people today bear Norman-derived surnames such as Burke, Roche and Power, although these are more prevalent in the provinces of Leinster and Munster, where there was a larger Norman presence.

As in England, the Normans blended the continental European county with the English shire, where the king's chief law enforcer was the shire-reeve (sheriff).

The traditional Irish legal system, the "Brehon Law", continued in areas outside central control, but the Normans introduced Henry II's reforms including new concepts such as prisons for criminals.

While the Norman political impact was considerable, it was untidy and not uniform, and the stresses on the Lordship in 1315–48 meant that de facto control of most of Ireland slipped from its grasp for over two centuries.

Initially the Normans controlled large swathes of Ireland, securing the entire east coast, from Waterford up to eastern Ulster and penetrating as far west as Gaillimh (Galway) and Maigh Eo (Mayo).

The most powerful forces in the land were the great Hiberno-Norman Earldoms such as the Geraldines, the Butlers and the de Burghs (Burkes), who controlled vast territories which were almost independent of the governments in Dublin or London.

Secondly a lack of direction from both Henry III and his successor Edward I (who were more concerned with events in Great Britain and their continental domains) meant that the Norman colonists in Ireland were to a large extent deprived of (financial) support from the English monarchy, limiting their ability to hold territory.

Politics and events in Gaelic Ireland served to draw the settlers deeper into the orbit of the Irish, which on occasion had the effect of allying them with one or more native rulers against other Normans.

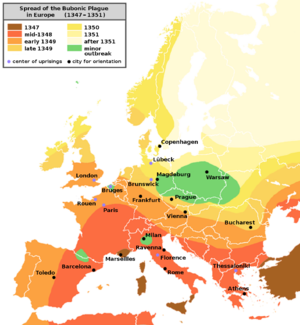

Hiberno-Norman Ireland was deeply shaken by four events in the 14th century: In the background the Hundred Years' War of 1337–1453 between the English and French dynasties drew off forces that could have protected the Lordship from attack by autonomous Gaelic and Norman lords.

Additional causes of the Gaelic revival were political and personal grievances against the Hiberno-Normans, but especially impatience with procrastination and the very real horrors that successive famines had brought.

At the same time, local Gaelic and Gaelicised lords expanded their powers at the expense of the Pale, creating a policy quite alien to English ways and which was not fully overthrown until the Tudor re-conquest of Ireland.