Nuclear envelope

[8] While it is physically linked, the outer nuclear membrane contains proteins found in far higher concentrations than the endoplasmic reticulum.

[13][14] Nesprin-3 and -4 may play a role in unloading enormous cargo; Nesprin-3 proteins bind plectin and link the nuclear envelope to cytoplasmic intermediate filaments.

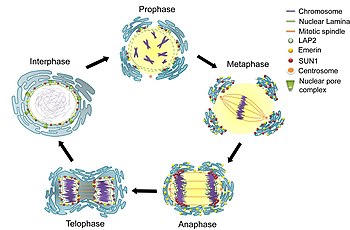

[9] In eukaryotes such as yeast which undergo closed mitosis, the nuclear membrane stays intact during cell division.

[9] In other eukaryotes (animals as well as plants), the nuclear membrane must break down during the prometaphase stage of mitosis to allow the mitotic spindle fibers to access the chromosomes inside.

In mammals, the nuclear membrane can break down within minutes, following a set of steps during the early stages of mitosis.

Biochemical evidence suggests that the nuclear pore complexes disassemble into stable pieces rather than disintegrating into small polypeptide fragments.

Thus the survival of cells migrating through confined environments appears to depend on efficient nuclear envelope and DNA repair machineries.

Aberrant nuclear envelope breakdown has also been observed in laminopathies and in cancer cells leading to mislocalization of cellular proteins, the formation of micronuclei and genomic instability.

Two theories exist[9]— A study of the comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear membrane led to the proposal that the nucleus emerged in the primitive eukaryotic ancestor (the “prekaryote”), and was triggered by the archaeo-bacterial symbiosis.

The adaptive function of the nuclear membrane may have been to serve as a barrier to protect the genome from reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by the cells' pre-mitochondria.