Knockout mouse

By causing a specific gene to be inactive in the mouse, and observing any differences from normal behaviour or physiology, researchers can infer its probable function.

[1][2] The first recorded knockout mouse was created by Mario R. Capecchi, Martin Evans, and Oliver Smithies in 1989, for which they were awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Consequently, observing the characteristics of knockout mice gives researchers information that can be used to better understand how a similar gene may cause or contribute to disease in humans.

For example, the p53 knockout mouse is named after the p53 gene which codes for a protein that normally suppresses the growth of tumours by arresting cell division and/or inducing apoptosis.

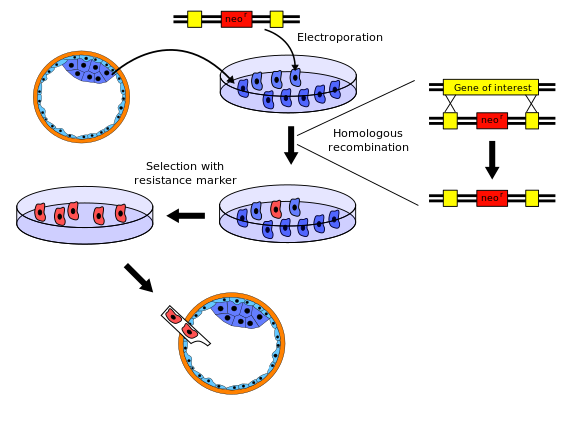

A detailed explanation of how knockout (KO) mice are created is located at the website of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2007.

About 15 percent of gene knockouts are developmentally lethal, which means that the genetically altered embryos cannot grow into adult mice.

The lack of adult mice limits studies to embryonic development and often makes it more difficult to determine a gene's function in relation to human health.

Another serious limitation is a lack of evolutive adaptations in knockout model that might occur in wild type animals after they naturally mutate.