Obsidian use in Mesoamerica

Obsidian was a highly integrated part of daily and ritual life, and its widespread and varied use may be a significant contributor to Mesoamerica's lack of metallurgy.

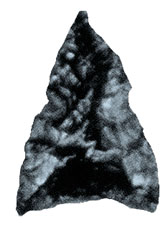

Due to its glassy internal structure, obsidian is relatively easy to work, as it breaks in very predictable and controlled ways via conchoidal fracturing.

Following the removal of cortex (when applicable), bifacial, unifacial, and expedient flake stone tools could be produced through lithic reduction.

Modern attempts to redesign production techniques are heavily based on Spanish records and accounts of witnessed obsidian knapping.

While prismatic blades were generally not curated (in the traditional sense) due to their small size, utility of the tools may have been maintained by changing their function.

Obsidian sources in Mesoamerica are limited in number and distribution, and are restricted to the volcanic regions of the Sierra Madre Mountains as they run through Mexico and Guatemala.

As mentioned earlier, the Guatemalan region includes the El Chayal, Ixtepeque, and San Martin Jilotepeque sources, located in southern/southeastern Guatemala.

Obsidian originating from Guatemala was widely used in Mesoamerica and is found as far north as the Yucatán Peninsula, moving via a well-developed long-distance trade network that inter-connected much of the Maya area.

Neutron activation analysis (NAA) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) are two analytical methods used to identify the types and amounts of trace elements.

The degree of hydration (i.e., water absorbed into the material) observed indicates how long it has been since the obsidian surface was exposed (i.e., through flaking).

It is unclear if trade for foreign obsidian contributed to the growth of Maya polities, or if it simply served as a mode for obtaining superior items or human labor.

Of primary importance is the circum-peninsular trade route that linked the southeast Maya area to the Gulf coast of Mexico.

Some non-utilitarian forms include miniature human effigies, ear spools and labrets with gold and turquoise workings, carved animal figurines, beads, vases, and as pieces of masks.

Its association with that act of bloodletting is important, as it is argued by some researchers[6] that obsidian was seen as a type of blood originating from the earth – its use in autosacrifice is therefore especially symbolic.

For example, flakes have been found in association with stelae offerings and related to specific gods at the Maya site of Tikal.

Unfortunately, the majority of the material record is out of context yet the implications and interpretations that are drawn from artwork are substantial and reflect a corpus of beliefs and ideology involving obsidian.

Earlier depictions of obsidian is usually restricted to their appearance as razors or lancets, and it is commonly believed that the material was not associated with weapons such as clubs or spears until later phases in Mesoamerica.

In the Aztec writing system, a curved prismatic blade represents the phonetic value itz (Taube 1991) and results in the term itztli, as mentioned.

For example, during the Preclassic period, obsidian was a rare item in the lowland areas, found predominantly in high-status and ritual contexts.