Seabed

Seafloor spreading creates mid-ocean ridges along the center line of major ocean basins, where the seabed is slightly shallower than the surrounding abyssal plain.

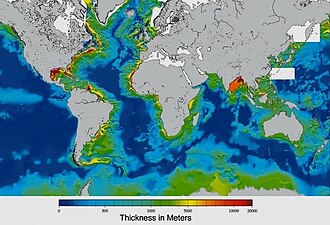

Categorized by where the materials come from or composition, these sediments are classified as either: from land (terrigenous), from biological organisms (biogenous), from chemical reactions (hydrogenous), and from space (cosmogenous).

Examples of human effects on the seabed include exploration, plastic pollution, and exploitation by mining and dredging operations.

Exploitation of the seabed involves extracting valuable minerals from sulfide deposits via deep sea mining, as well as dredging sand from shallow environments for construction and beach nourishment.

Deep ocean water is divided into layers or zones, each with typical features of salinity, pressure, temperature and marine life, according to their depth.

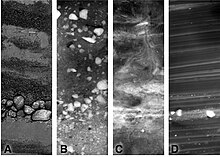

Fluvial sediments are transported from land by rivers and glaciers, such as clay, silt, mud, and glacial flour.

Calcareous oozes are predominantly composed of calcium shells found in phytoplankton such as coccolithophores and zooplankton like the foraminiferans.

[9] Cosmogenous sediments are the remains of space debris such as comets and asteroids, made up of silicates and various metals that have impacted the Earth.

[13] This community lives in or near marine or freshwater sedimentary environments, from tidal pools along the foreshore, out to the continental shelf, and then down to the abyssal depths.

Tidal networks depend on the balance between sedimentary processes and hydrodynamics however, anthropogenic influences can impact the natural system more than any physical driver.

Some features of the seabed include flat abyssal plains, mid-ocean ridges, deep trenches, and hydrothermal vents.

[23] Large deep sea communities of marine life have been discovered around black and white smokers – vents emitting chemicals toxic to humans and most vertebrates.

This marine life receives its energy both from the extreme temperature difference (typically a drop of 150 degrees) and from chemosynthesis by bacteria.

They found the highly variable microplastic counts to be proportionate to plastic on the surface and the angle of the seafloor slope.

The main ores of commercial interest are polymetallic nodules, which are found at depths of 4–6 km (2.5–3.7 mi) primarily on the abyssal plain.

The Clarion–Clipperton zone (CCZ) alone contains over 21 billion metric tons of these nodules, with minerals such as copper, nickel, and cobalt making up 2.5% of their weight.

It is estimated that the global ocean floor holds more than 120 million tons of cobalt, five times the amount found in terrestrial reserves.

[34] In 2022, the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA) granted three exploration licenses for cobalt-rich polymetallic nodules within their EEZ.

[35] Papua New Guinea was the first country to approve a deep sea mining permit for the Solwara 1 project, despite three independent reviews highlighting significant gaps and flaws in the environmental impact statement.

[36] The most common commercial model of deep sea mining proposed involves a caterpillar-track hydraulic collector and a riser lift system bringing the harvested ore to a production support vessel with dynamic positioning, and then depositing extra discharge down the water column.

Related technologies include robotic mining machines, as surface ships, and offshore and onshore metal refineries.

[37] Electric vehicle batteries are the main driver of the critical metals demand that incentivizes deep sea mining.

[45] Opposition campaigns enlisted the support of some industry figures, including firms reliant on the target metals.

The convention aims at preventing looting and the destruction or loss of historic and cultural information by providing an international legal framework.