Ocean fertilization

More than a dozen open-sea experiments confirmed that adding iron to the ocean increases photosynthesis in phytoplankton by up to 30 times.

A 2021 report on CDR indicates that there is medium-high confidence that the technique could be efficient and scalable at low cost, with medium environmental risks.

Peter Fiekowsky and Carole Douglis write "I consider iron fertilization an important item on our list of pottential climate restoration solutions.

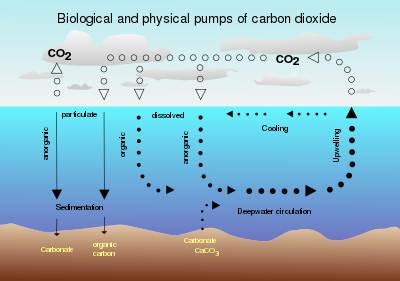

The "biological" pump is driven by phytoplankton and subsequent settling of detrital particles or dispersion of dissolved organic carbon.

These include macronutrients such as nitrate and phosphate (in relatively high concentrations) and micronutrients such as iron and zinc (in much smaller quantities).

Nitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria provides a major source of N. In effect, it ultimately prevents the ocean from losing the N required for photosynthesis.

[18] Since 1990, 13 major large scale experiments have been carried out to evaluate efficiency and possible consequences of iron fertilization in ocean waters.

A study in 2017 considered that the method is unproven; the sequestering efficiency was low and sometimes no effect was seen and the amount of iron deposits needed to make a small cut in the carbon emissions would be in the million tons per year.

[19] However since 2021, interest is renewed in the potential of iron fertilization, among other from a white paper study of NOAA, the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, which rated iron fertilization as having "moderate potential for cost, scalability and how long carbon might be stored compared to other marine sequestration ideas" In the very long term, phosphorus "is often considered to be the ultimate limiting macronutrient in marine ecosystems"[21] and has a slow natural cycle.

This technique can give 0.83 W/m2 of globally averaged negative forcing,[22] which is sufficient to reverse the warming effect of about half the current levels of anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

[9] This technique proposes to fertilize the ocean with urea, a nitrogen rich substance, to encourage phytoplankton growth.

[27] This project was criticized by many institutions, including the European Commission,[28] due to lack of knowledge of side effects on the marine ecosystem.

[29] Macronutrient nourishment can give 0.38 W/m2 of globally averaged negative forcing,[22] which is sufficient to reverse the warming effect of current levels of around a quarter of anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

[30] In waters with sufficient iron micro nutrients, but a deficit of nitrogen, urea fertilization is the better choice for algae growth.

[35] Scientists also emphasize that adding urea to ocean waters could reduce oxygen content and result in a rise of toxic marine algae.

In August 2008 the Kasatochi volcanic eruption in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, deposited ash in the nutrient-limited northeast Pacific.

[41][42] Fisheries scientists in Canada linked increased oceanic productivity from the volcanic iron to subsequent record returns of salmon in the Fraser River two years later[43] The approach advocated by Ocean Nutrition Corporation is to limit the distribution of added nutrients to allow phytoplankton concentrations to rise only to the values seen in upwelling regions (5–10 mg Chl/m3).

[44] SS While manipulation of the land ecosystem in support of agriculture for the benefit of humans has long been accepted (despite its side effects), directly enhancing ocean productivity has not.

But key questions remain,says Dave Siegel, a marine scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who served on the NASEM panel.

"[22] Beyond biological impacts, evidences suggests that plankton blooms can affect the physical properties of surface waters simply by absorbing light and heat from the sun.

In addition, as the bloom declines, nitrous oxide is released, potentially counteracting the effects from the sequestering of carbon.

[53] Adding urea to the ocean can cause phytoplankton blooms that serve as a food source for zooplankton and in turn feed for fish.

[58] As the phytoplankton descend the water column, they decay, consuming oxygen and producing greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide.

[45] Many phytoplankton species release dimethyl sulfide (DMS), which escapes into the atmosphere where it forms sulfate aerosols and encourages cloud formation, which could reduce warming.

[59][60] In 2007 Working Group III of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change examined ocean fertilization methods in its fourth assessment report and noted that the field-study estimates of the amount of carbon removed per ton of iron was probably over-estimated and that potential adverse effects had not been fully studied.

[citation needed] In 2008, the London Convention/London Protocol noted in resolution LC-LP.1 that knowledge on the effectiveness and potential environmental impacts of ocean fertilization was insufficient to justify activities other than research.

This non-binding resolution stated that fertilization, other than research, "should be considered as contrary to the aims of the Convention and Protocol and do not currently qualify for any exemption from the definition of dumping".

[63] In May 2008, at the Convention on Biological Diversity, 191 nations called for a ban on ocean fertilization until scientists better understand the implications.

[64] In August 2018, Germany banned the sale of ocean seeding as carbon sequestration system[65] while the matter was under discussion at EU and EASAC levels.

[citation needed] The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC 1992) has accepted mitigation actions.

2 sequestration in the ocean