Octant (instrument)

It is not known why Halley did not publish the information during his life, as this prevented Newton from getting the credit for the invention that is generally given to John Hadley and Thomas Godfrey.

This fineness of graduation is only possible due to the large size of the instrument - the sighting telescope alone was three to four feet long.

Short–focal length telescopes, prior to the development of achromatic lenses, produced an objectionable degree of aberration, so much so that it could affect the perception of a star's position.

Two men independently developed the octant around 1730: John Hadley (1682–1744), an English mathematician, and Thomas Godfrey (1704–1749), a glazier in Philadelphia.

While both have a legitimate and equal claim to the invention, Hadley generally gets the greater share of the credit.

This reflects the central role that London and the Royal Society played in the history of scientific instruments in the eighteenth century.

Two others who created octants during this period were Caleb Smith, an English insurance broker with a strong interest in astronomy (in 1734), and Jean-Paul Fouchy, a mathematics professor and astronomer in France (in 1732).

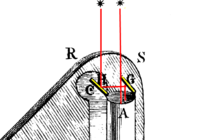

In the image at the right, from Hadley's article in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society,[4] you can see the nature of his design.

A second, smaller horizon mirror was mounted on the frame in the line of sight of the telescope.

Moving the index arm allowed the navigator to see any object within 90° of the direct view.

It could be remounted so that the telescope viewed the second horizon mirror from the opposite side of the frame.

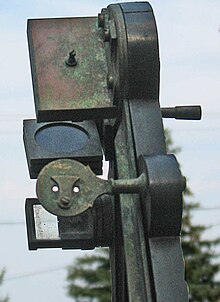

Comparing this instrument to the photo of a typical octant at the top of the article, one can see that the only significant differences in the more modern design are: Caleb Smith, an English insurance broker with a strong interest in astronomy, had created an octant in 1734.

Smith called the instrument's index arm a label, in the manner of Elton for his mariner's quadrant.

[7] Various design elements of Smith's instrument made it inferior to Hadley's octant and it was not used significantly.

The sight was easy to align because the horizon and the star seem to move together as the ship pitched and rolled.

[5] Early octants were constructed primarily in wood, with later versions incorporating ivory and brass components.

The poor optical quality of the early polished speculum metal mirrors meant that telescopic sights were not practical.

In wood and ivory, their relatively low price compared to an all-brass sextant made them a popular instrument.

In 1767 the first edition of The Nautical Almanac tabulated lunar distances, enabling navigators to find the current time from the angle between the Sun and the Moon.

For that reason, Admiral John Campbell, who conducted shipboard experiments with the lunar distance method, suggested a larger instrument and the sextant was developed.

The octant continued to be produced well into the 19th century, though it was generally a less accurate and less expensive instrument.

The lower price of the octant, including versions without telescope, made it a practical instrument for ships in the merchant and fishing fleets.

The sextant was used with great care and only for lunars, while the octant was used for routine meridional altitude measurements of the Sun every day.

From the early 1930s through the end of the 1950s, several types of civilian and military bubble octant instruments were produced for use aboard aircraft.

[14] Other octants were developed by Jean-Paul Fouchy and Caleb Smith in the early 1730s, however, these did not become significant in the history of navigation instruments.

CD – index arm

G – horizon mirror

H – index mirror

PQ – graduated arc