Esophagus

The esophagus is a fibromuscular tube, about 25 cm (10 in) long in adults, that travels behind the trachea and heart, passes through the diaphragm, and empties into the uppermost region of the stomach.

The word esophagus is from Ancient Greek οἰσοφάγος (oisophágos), from οἴσω (oísō), future form of φέρω (phérō, "I carry") + ἔφαγον (éphagon, "I ate").

The esophagus may be affected by gastric reflux, cancer, prominent dilated blood vessels called varices that can bleed heavily, tears, constrictions, and disorders of motility.

Clinical investigations include X-rays when swallowing barium sulfate, endoscopy, and CT scans.

Surgically, the esophagus is difficult to access in part due to its position between critical organs and directly between the sternum and spinal column.

[3] It begins at the back of the mouth, passing downward through the rear part of the mediastinum, through the diaphragm, and into the stomach.

[6] The upper esophagus lies at the back of the mediastinum behind the trachea, adjoining along the tracheoesophageal stripe, and in front of the erector spinae muscles and the vertebral column.

The primary muscle of the upper esophageal sphincter is the cricopharyngeal part of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor.

[6] The vagus nerve has a parasympathetic function, supplying the muscles of the esophagus and stimulating glandular contraction.

The upper striated muscle, and upper esophageal sphincter, are supplied by neurons with bodies in the nucleus ambiguus, whereas fibers that supply the smooth muscle and lower esophageal sphincter have bodies situated in the dorsal motor nucleus.

It may enhance the function of the vagus nerve, increasing peristalsis and glandular activity, and causing sphincter contraction.

In addition, sympathetic activation may relax the muscle wall and cause blood vessel constriction.

[16] Normally, the cardia of the stomach is immediately distal to the z-line[17] and the z-line coincides with the upper limit of the gastric folds of the cardia; however, when the anatomy of the mucosa is distorted in Barrett's esophagus the true gastroesophageal junction can be identified by the upper limit of the gastric folds rather than the mucosal transition.

[6] The human esophagus has a mucous membrane consisting of a tough stratified squamous epithelium without keratin, a smooth lamina propria, and a muscularis mucosae.

[6] The epithelium of the esophagus has a relatively rapid turnover and serves a protective function against the abrasive effects of food.

[21] The submucosa also contains the submucosal plexus, a network of nerve cells that is part of the enteric nervous system.

These are separated by the myenteric plexus, a tangled network of nerve fibers involved in the secretion of mucus and in peristalsis of the smooth muscle of the esophagus.

Sections of this gut begin to differentiate into the organs of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, and intestines.

Reflux of gastric acids from the stomach, infection, substances ingested (for example, corrosives), some medications (such as bisphosphonates), and food allergies can all lead to esophagitis.

[5] Prolonged esophagitis, particularly from gastric reflux, is one factor thought to play a role in the development of Barrett's esophagus.

Achalasia refers to a failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax properly, and generally develops later in life.

[5] The word esophagus (British English: oesophagus), comes from the Greek: οἰσοφάγος (oisophagos) meaning gullet.

[33] The use of the word esophagus, has been documented in anatomical literature since at least the time of Hippocrates, who noted that "the oesophagus ... receives the greatest amount of what we consume.

In the majority of vertebrates, the esophagus is simply a connecting tube, but in some birds, which regurgitate components to feed their young, it is extended towards the lower end to form a crop for storing food before it enters the true stomach.

However, some fish, including lampreys, chimaeras, and lungfish, have no true stomach, so that the esophagus effectively runs from the pharynx directly to the intestine, and is therefore somewhat longer.

[39] In addition, in the bat Plecotus auritus, fish and some amphibians, glands secreting pepsinogen or hydrochloric acid have been found.

[45] A structure with the same name is often found in invertebrates, including molluscs and arthropods, connecting the oral cavity with the stomach.

[46] In terms of the digestive system of snails and slugs, the mouth opens into an esophagus, which connects to the stomach.

Because of torsion, which is the rotation of the main body of the animal during larval development, the esophagus usually passes around the stomach, and opens into its back, furthest from the mouth.

In species that have undergone de-torsion, however, the esophagus may open into the anterior of the stomach, which is the reverse of the usual gastropod arrangement.

- esophagus

- trachea

- tracheal lungs

- rudimentary left lung

- right lung

- heart

- liver

- stomach

- air sac

- gallbladder

- pancreas

- spleen

- intestine

- testicles

- kidneys

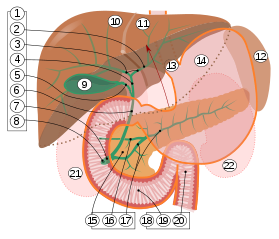

2. Intrahepatic bile ducts

3. Left and right hepatic ducts

4. Common hepatic duct

5. Cystic duct

6. Common bile duct

7. Ampulla of Vater

8. Major duodenal papilla

9. Gallbladder

10–11. Right and left lobes of liver

12. Spleen

13. Esophagus

14. Stomach

15. Pancreas :

16. Accessory pancreatic duct

17. Pancreatic duct

18. Small intestine :

19. Duodenum

20. Jejunum

21–22. Right and left kidneys

The front border of the liver has been lifted up (brown arrow). [ 38 ]