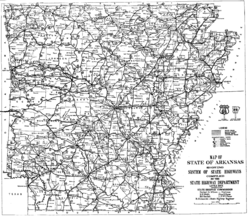

Arkansas Highway System

In the late nineteenth century, travelers would follow dirt paths riddled with potholes, and ruts.

Trains never became popular in Arkansas, and instead travelers would use horse and buggy to get around the rural parts of state, and bicycles within cities.

A group of Arkansas cyclists held a good roads convention in Little Rock just before the turn of the century.

[3] The enterprising salesmen greatly increased the movement's breadth by expanding their scope outside of city streets to farm to market routes, a move that enticed farmers to support the cause.

The combination of money from Little Rock salesmen and the large number of farmers in the state made the good roads movement a formidable alliance.

Today, the route is mostly covered by Highway 365, although some original concrete segments are still visible, and the Dollarway Road portion has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

[7] Now that Arkansas had discovered a durable paving system, concrete topped with asphalt of "Dollarway pavement", they could replace the often-broken macadam roads.

As Arkansans sought improved roads across the state, the General Assembly eschewed centralized planning and financing of transportation corridors, instead passing a law allowing local adjacent property owners to design, construct, and issue bonds for roads within their boundaries.

The system led to a fractured series of roadways with inconsistent quality rather than a network, and was often driven by provincial interests, corruption, and fraud.

In 1915, the Commission was charged with misappropriating funds for officials to use on automobiles and gasoline, making the financial situation even worse.

The Alexander Road law of 1915 allowed those close to a route to form their own districts and subsequently contract out the work themselves.

The Arkansas legislature was slow to create an authority capable of meeting the Federal Aid Act's requirements, opting instead to stay with the district approach, which cost the state millions of dollars in funds.

When the General Assembly again tried to create one, the local county judges (usually profiting from the exorbitant district fees) blocked the legislation.

Upon withdrawal of federal money in 1923, Governor Thomas McRae called a special session of the General Assembly to solve the problem.

The most significant provision of the law created a state highway system, and the roads within it were eligible for federal funding to be disbursed by the Commission.

The Commission gained significant influence over construction by having the ability to disburse federal aid to projects meeting its standards.

Sid McMath, ran on a platform of business progressivism, with highway reform as the cornerstone issue.

Taking over as governor after the 1948 election, McMath and the General Assembly passed a bond measure to raise construction and maintenance funds for roads and bridges.

[a] An audit commission of the Highway Department found widespread corruption and cronyism in early 1952, slowing McMath's reform efforts.

He was ousted that fall and replaced by a more conservative Francis Cherry, who sought reforms within the Highway Department.

Arkansas decided not to begin a comprehensive program, and instead discovered that thousands of miles should no longer even receive county funding due to heavy population losses.

[23] 1957 brought the Milum Road Act, which created (at minimum) eleven additional miles of state highways in each of Arkansas' 75 counties.

Despite the creation of a highway department and numerous attempts to keep politics away from road funding, the system is still flawed.

[24] Arkansas' highway system was consistently ranked one of America's worst until the AHTD launched a $575 million program in 1999.

Arkansas is also working to bring Interstate 49 along its western edge, eventually connecting Kansas City and New Orleans.

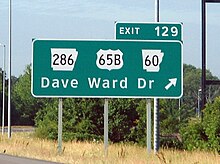

This is the procedure for all highways in Arkansas, unless an officially designated "exception" occurs, which means a concurrency does form.

Major changes usually involve Arkansas's eastern border along the Mississippi River and the Missouri Bootheel.

The state line is indeterminate along the Mississippi River, and different variants have different levels of accuracy along the eastern border.

In the field, however, signs posted by municipalities sometimes lack the "Arkansas" banner and often use non-standard numbering font.

[28] The local road system encompasses dead ends or other highways that would generally not be used by the traveling public, except for adjacent property owners.