Oil and gas industry in the United Kingdom

Oil and gas are also major feedstocks for the petrochemicals industries producing pharmaceuticals, plastics, cosmetics and domestic appliances.

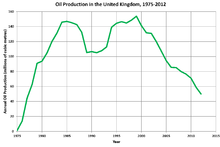

In 2013 the UK consumed 1.508 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil and 2.735 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas,[5] so is now an importer of hydrocarbons having been a significant exporter in the 1980s and 1990s.

Historically most gas came from Morecambe Bay and the Southern North Sea off East Anglia and Lincolnshire, but both areas are now in decline.

[7] The only major onshore field is Wytch Farm in Dorset but there are a handful oil wells scattered across England.

The UK's strengths in financial services have led it to play a leading role in energy trading through markets such as ICE Futures (formerly the International Petroleum Exchange).

The outbreak of World War II accelerated this search and led to a number of wells being drilled, primarily around Eakring in the East Midlands near Sherwood Forest.

[13] In the 1950s, the focus turned to southern England where oil was discovered in the Triassic Sherwood Sands formation at 1,600 metres (5,200 ft), followed by the development of the Wytch Farm oilfield.

The link between onshore and offshore oil in the North Sea was made after the discovery of the Groningen gas field in The Netherlands in 1959.

This represented a fall of 5% compared with 2007 (6% oil and 3% gas), a slight improvement on the decline rate in 2002-2007 which averaged 7.5% per annum.

Whilst the oil and gas industry provides work across the whole of the UK, Scotland benefits the most, with around 195,000 jobs, or 44% of the total.

[22] Set up in 1996, First Point Assessment Limited (FPAL)[31] is the key tool used by oil and gas companies to identify and select current and potential suppliers when awarding contracts or purchase orders.

2008 salaries averaged circa £50,000 a year across a broad sample of supply chain companies, with the Exchequer benefiting by £19,500 per head in payroll taxes.

To overcome the challenges of recovering oil and gas from increasingly difficult reservoirs and deeper waters, the North Sea has developed a position at the forefront of offshore engineering, particularly in subsea technology.

Often recovery from these fields is achieved by subsea developments tied back to existing installations and infrastructure, over varying distances measured in tens of kilometres.

[33] Following the Piper Alpha disaster in 1988, the 106 recommendations of the Public Inquiry by Lord Cullen proposed fundamental changes to the regulation of offshore safety.

[35] The Health & Safety Executive (HSE)[36] is the UK offshore oil and gas industry regulator and is organised into a number of directorates.

The Fisheries Legacy Trust Company's (FLTC)[41] main function is to help keep fishermen safe in UK waters.

It does this by building a trust fund (based on payments from oil and gas producers) which can be used to maintain comprehensive, up-to-date information on all seabed hazards related to oil and gas activities for as long as they remain, and to make this data available for use by fishing vessel plotters found on board in wheelhouses all around the UK coastline.

[43] The low temperature of combustion in open flaring, and incomplete mixing of oxygen means that carbon in methane may not be burned, leading to a sooty smoke, and potential VOC/BTEX contamination.

In 2007, 59 tonnes of oil in total[42] was accidentally released into the marine environment, which, in open sea, will have a negligible environmental impact.

Types of waste generated offshore vary and include drill cuttings and powder, recovered oil, crude contaminated material, chemicals, drums, containers, sludges, tank washings, scrap metal and segregated recyclables.

The majority of wastes produced offshore are transferred onshore where the main routes of disposal are landfill, incineration, recycling and reuse.

Under OSPAR legislation, only installations that fulfil certain criteria (on the grounds of safety and/or technical limitations) are eligible for derogation (that is, leaving the structure, or part of, in place on the seabed).

During the next two decades, the industry will begin to decommission many of the installations that have been producing oil and gas for the past forty years.

Decommissioning is a complex process, representing a considerable challenge on many fronts and encompassing technical, economic, environmental, health and safety issues.

Marine technology, skills and expertise pioneered in oil and gas are important in the design, installation and maintenance of offshore wind turbines and hence have found roles in the continuing evolution of renewable energy.

All three areas of expertise are used by scientists and engineers elsewhere, whether examining Antarctic ice core samples, raising sunken ship wrecks or studying the plate tectonics of the ocean floor.

To prevent carbon dioxide building up in the atmosphere it has been theorised that it can be captured and stored, such as the working CCS at the Sleipner field offshore Norway, among other examples.

CCS is undertaken by combining three distinct processes: capturing the carbon dioxide at a power station or other major industrial plant, transporting it by pipeline or by tanker, and then storing it in geological formations.

The oil and gas industry's knowledge of undersea geology, reservoir management and pipeline transport will play an important role in making this technology work effectively.