Italian language

The Italian language has developed through a long and slow process, which began after the Western Roman Empire's fall and the onset of the Middle Ages in the 5th century.

Over centuries, the Vulgar Latin popularly spoken in various areas of Europe—including the Italian Peninsula—evolved into local varieties, or dialects, unaffected by formal standards and teachings.

The earliest surviving texts that can definitely be called vernacular (as distinct from its predecessor Vulgar Latin) are legal formulae known as the Placiti Cassinesi from the province of Benevento that date from 960 to 963, although the Veronese Riddle, probably from the 8th or early 9th century, contains a late form of Vulgar Latin that can be seen as a very early sample of a vernacular dialect of Italy.

The language that came to be thought of as Italian developed in central Tuscany and was first formalized in the early 14th century through the works of Tuscan writer Dante Alighieri, written in his native Florentine.

Dante's epic poems, known collectively as the Commedia, to which another Tuscan poet Giovanni Boccaccio later affixed the title Divina, were read throughout the Italian peninsula.

The poetry of Petrarch was also widely admired and influential in the development of the literary language, and would be identified as a model for vernacular writing by Pietro Bembo in the 16th century.

The increasing political and cultural relevance of Florence during the periods of the rise of the Medici Bank, humanism, and the Renaissance made its dialect, or rather a refined version of it, a standard in the arts.

The printing press enabled the production of literature and documents in higher volumes and at lower cost, further accelerating the spread of Italian.

The rediscovery of Dante's De vulgari eloquentia, and a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language.

An important event that helped the diffusion of Italian was the conquest and occupation of Italy by Napoleon (himself of Italian-Corsican descent) in the early 19th century.

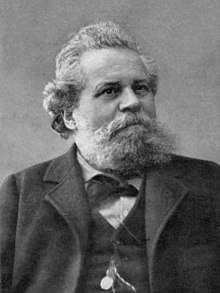

Manzoni, a Milanesian, chose to write the book in the Florentine dialect, describing this choice, in the preface to his 1840 edition, as "rinsing" his Milanese "in the waters of the Arno" (Florence's river).

[38][39] After Unification, a huge number of civil servants and soldiers recruited from all over the country introduced many more words and idioms from their home languages.

[41] A 1949 study by the linguist Mario Pei concluded that out of seven Romance languages, Italian's stressed vowel phonology was the second-closest to that of Vulgar Latin (after Sardinian).

[55] Italian served as Malta's official language until 1934, when it was abolished by the British colonial administration amid strong local opposition.

[75] The main Italian-language newspapers published outside Italy are the L'Osservatore Romano (Vatican City), the L'Informazione di San Marino (San Marino), the Corriere del Ticino and the laRegione Ticino (Switzerland), the La Voce del Popolo (Croatia), the Corriere d'Italia (Germany), the L'italoeuropeo (United Kingdom), the Passaparola (Luxembourg), the America Oggi (United States), the Corriere Canadese and the Corriere Italiano (Canada), the Il punto d'incontro (Mexico), the L'Italia del Popolo (Argentina), the Fanfulla (Brazil), the Gente d'Italia (Uruguay), the La Voce d'Italia (Venezuela), the Il Globo (Australia) and the La gazzetta del Sud Africa (South Africa).

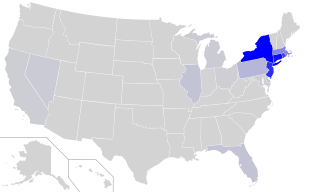

[81] From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, millions of Italians settled in Argentina, Uruguay, southern Brazil, and Venezuela, and in Canada and the United States, where they formed a physical and cultural presence.

Examples are Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where Talian is used, and the town of Chipilo near Puebla, Mexico; each continues to use a derived form of Venetian dating back to the 19th century.

A mark of the educated gentlemen was to make the Grand Tour, visiting Italy to see its great historical monuments and works of art.

On the other hand, Corsican (a language spoken on the French island of Corsica) is closely related to medieval Tuscan, from which standard Italian derives and evolved.

The most prevalent were substrata (the language of the original inhabitants), as the Italian dialects were most probably simply Latin as spoken by native cultural groups.

Regional differences can be recognized by various factors: the openness of vowels, the length of the consonants, and influence of the local language (for example, in informal situations andà, annà and nare replace the standard Italian andare in the area of Tuscany, Rome and Venice respectively for the infinitive "to go").

There is no definitive date when the various Italian variants of Latin—including varieties that contributed to modern standard Italian—began to be distinct enough from Latin to be considered separate languages.

Nevertheless, on the basis of accumulated differences in morphology, syntax, phonology, and to some extent lexicon, it is not difficult to identify that for the Romance varieties of Italy, the first extant written evidence of languages that can no longer be considered Latin comes from the 9th and 10th centuries CE.

An increase in literacy was one of the main driving factors (one can assume that only literates were capable of learning standard Italian, whereas those who were illiterate had access only to their native dialect).

In addition, other factors such as mass emigration, industrialization, and urbanization, and internal migrations after World War II, contributed to the proliferation of standard Italian.

The following are some of the conservative phonological features of Italian, as compared with the common Western Romance languages (French, Spanish, Portuguese, Galician, Catalan).

Dual outcomes of Latin /p t k/ between vowels, such as lŏcvm > luogo but fŏcvm > fuoco, was once thought to be due to borrowing of northern voiced forms, but is now generally viewed as the result of early phonetic variation within Tuscany.

Especially people from the northern part of Italy (Parma, Aosta Valley, South Tyrol) may pronounce /r/ as [ʀ], [ʁ], or [ʋ].

The form-changing adjectives "buono (good), bello (beautiful), grande (big), and santo (saint)" change in form when placed before different types of nouns.

Stressed object pronouns come after the verb, and are used when the emphasis is required, for contrast, or to avoid ambiguity (Vedo lui, ma non lei.