Operation Michael

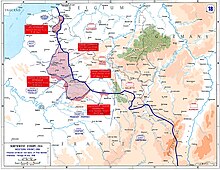

Operation Michael failed to achieve its objectives and the German advance was reversed during the Second Battle of the Somme, 1918 (21 August – 3 September) in the Allied Hundred Days Offensive.

Their target was the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), commanded by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, which they believed had been exhausted by the battles in 1917 at Arras, Messines, Passchendaele and Cambrai.

The "line", taken over from the French, barely existed, needing much work to make it easily defensible to the positions further north, which slowed progress in the area of the Fifth Army (General Hubert Gough).

[9] The BEF had been reorganised due to a lack of infantry replacements; divisions were reduced from twelve to nine battalions, on the model established by the German and French armies earlier in the war.

The Germans had developed stormtrooper (Stoßtruppen) units, elite infantry which used infiltration tactics, operating in small groups that advanced quickly by exploiting gaps and weak defences.

This process gave the German army an initial advantage in the attack but meant that the best troops would suffer disproportionate casualties, while the men in reserve were of lower quality.

"[14] The last German offensive on the Western Front, before the Cambrai Gegenschlag (counter-stroke) of December 1917, had been against the French at Verdun, giving the British commanders little experience in defence.

This reduced the proportion of troops in the front line, which was lightly held by snipers, patrols and machine-gun posts and concentrated reserves and supply dumps to the rear, away from German artillery.

An average British division in 1918 consisted of 11,800 men, 3,670 horses and mules, 48 artillery pieces, 36 mortars, 64 Vickers heavy machine guns, 144 Lewis light machine-guns, 770 carts and wagons, 360 motorcycles and bicycles, 14 trucks, cars and 21 motorised ambulances.

They reported massed trench mortars directly in front of 36th Division lines for wire cutting and an artillery bombardment, lasting several hours, as a preliminary to an infantry assault.

The fog and smoke from the bombardment made visibility poor throughout the day, allowing the German infantry to infiltrate deep behind the British front positions undetected.

[34] Much of the Forward Zone fell during the morning as communication failed; telephone wires were cut and runners struggled to find their way through the dense fog and heavy shelling.

The result of the misunderstanding between Gough and Maxse and different interpretations placed on boom messages and written orders, was that the 36th Division retired to Sommette-Eaucourt on the south bank of the Canal de Saint-Quentin, to form a new line of defence.

In the confusion, Brigade HQ tried to establish what was happening around Jussy and by late morning the British were retreating in front of German troops who had crossed the Crozat Canal at many points.

[52] Lieutenant Alfred Herring of the 6th Northamptonshire Battalion in the 54th Brigade, despite having never been in battle before, led a small and untried platoon as part of a counter-attack made by three companies, against German troops who had captured the Montagne Bridge on the Crozat Canal.

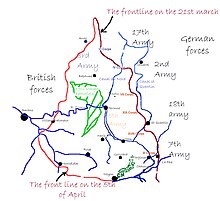

[55] By now, the front line was badly fragmented and highly fluid, as the remnants of the divisions of the Fifth Army were fighting and moving in small bodies, often composed of men of different units.

The official historian, Brigadier-General Sir James E. Edmonds wrote: After three days of battle, with each night spent on the march or occupied in the sorting out and reorganization of units, the troops – Germans as well as British – were tired almost to the limits of endurance.

[63]After three days the infantry was exhausted and the advance bogged down, as it became increasingly difficult to move artillery and supplies over the Somme battlefield of 1916 and the wasteland of the 1917 German retreat to the Hindenburg Line.

[66] In his diary entry for 24 March, Haig acknowledged important losses but derived comfort from the resilience of British rearguard actions, By night the Enemy had reached Le Transloy and Combles.

The traditional account, as repeated in Edmonds' Official History, composed during the 1920s, describes Petain as informing Haig on 24 March, that the French army were preparing to fall back towards Beauvais to protect Paris if the German advance continued.

Midday saw them in a stronger position until French artillery and machine guns opened fire on them, mistaking them for Germans, forcing them to retire to high ground west of Grandu.

Cooking limbers were even brought up and the idea of a quiet night gave the exhausted men a welcomed break from the extreme stress they had all been through in the past five days.

A number of others, finding their retreat cut off, surrendered to some infantry of the 51st Divn…"[80] Despite this success German pressure on Byng's southern flank and communication misunderstandings resulted in the premature retirement of units from Bray and the abandonment of the Somme crossings westwards.

Orders were given for the Bn to withdraw behind PROYART, astride the FOUCACOURT-MANOTTE road.French forces on the extreme right (south) of the line under the command of General Fayolle were defeated and fell back in the face of protracted fighting; serious gaps appeared between the retreating groups.

[85] [f] The 1/1st Herts war diary reads: The Bn who were in trenches on both sides of the road were ordered to move forward in support of the 118th Bde, being temporarily attached to the 4/5th Black Watch Regt.

In the evening the Bn went into trenches in front of AUBERCOURT.The Herts war diary reads: The enemy remained fairly quiet except for machine gun fire.The last general German attack came on 30 March.

The fighting was remarkable on two counts: the first use of tanks simultaneously by both sides in the war and a night counter-attack hastily organised by the Australian and British units (including the exhausted 54th Brigade) which re-captured Villers-Bretonneux and halted the German advance.

[citation needed] In Tad Williams' Otherland: City of Golden Shadow the first character introduced to the reader is Paul Jonas, who is fighting for the Allies on the Western Front somewhere near Ypres and Saint-Quentin on 24 March 1918.

The 1966 movie The Blue Max depicts Operation Michael as the big German offensive Bruno Stachel's (George Peppard) squadron is supporting with strafing attacks and aerial combat against Allied air forces.

At a squadron party celebrating one pilot's award of the Blue Max medal, the General (James Mason) announces the pending barrage of 6,000 guns on the Western Front, refers to the recent defeat of Russia which allowed the release of troops from the East to reinforce the Western armies, and expresses the hope of the High Command that victory in the offensive before America can effectively intervene will win the war for Germany.