Orbital hybridisation

Hybrid orbitals are useful in the explanation of molecular geometry and atomic bonding properties and are symmetrically disposed in space.

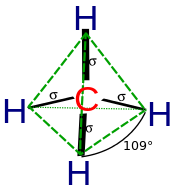

[1] Chemist Linus Pauling first developed the hybridisation theory in 1931 to explain the structure of simple molecules such as methane (CH4) using atomic orbitals.

[4] This concept was developed for such simple chemical systems, but the approach was later applied more widely, and today it is considered an effective heuristic for rationalizing the structures of organic compounds.

Hybridisation theory is an integral part of organic chemistry, one of the most compelling examples being Baldwin's rules.

For drawing reaction mechanisms sometimes a classical bonding picture is needed with two atoms sharing two electrons.

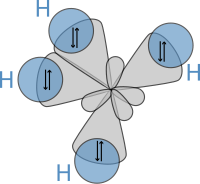

, where N is a normalisation constant (here 1/2) and pσ is a p orbital directed along the C-H axis to form a sigma bond.

These molecules tend to have multiple shapes corresponding to the same hybridization due to the different d-orbitals involved.

[13] In certain transition metal complexes with a low d electron count, the p-orbitals are unoccupied and sdx hybridisation is used to model the shape of these molecules.

[12][14][13] In some general chemistry textbooks, hybridization is presented for main group coordination number 5 and above using an "expanded octet" scheme with d-orbitals first proposed by Pauling.

In 1990, Eric Alfred Magnusson of the University of New South Wales published a paper definitively excluding the role of d-orbital hybridisation in bonding in hypervalent compounds of second-row (period 3) elements, ending a point of contention and confusion.

Part of the confusion originates from the fact that d-functions are essential in the basis sets used to describe these compounds (or else unreasonably high energies and distorted geometries result).

Specifically, hybridisation is not determined a priori but is instead variationally optimized to find the lowest energy solution and then reported.

This means that all artificial constraints, specifically two constraints, on orbital hybridisation are lifted: This means that in practice, hybrid orbitals do not conform to the simple ideas commonly taught and thus in scientific computational papers are simply referred to as spx, spxdy or sdx hybrids to express their nature instead of more specific integer values.

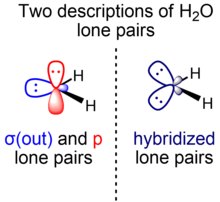

For example, the two bond-forming hybrid orbitals of oxygen in water can be described as sp4.0 to give the interorbital angle of 104.5°.

Hybridisation of s and p orbitals to form effective spx hybrids requires that they have comparable radial extent.

[21] However, computational VB groups such as Gerratt, Cooper and Raimondi (SCVB) as well as Shaik and Hiberty (VBSCF) go a step further to argue that even for model molecules such as methane, ethylene and acetylene, the hybrid orbitals are already defective and nonorthogonal, with hybridisations such as sp1.76 instead of sp3 for methane.

While this is true if Koopmans' theorem is applied to localized hybrids, quantum mechanics requires that the (in this case ionized) wavefunction obey the symmetry of the molecule which implies resonance in valence bond theory.

For example, in methane, the ionised states (CH4+) can be constructed out of four resonance structures attributing the ejected electron to each of the four sp3 orbitals.

For molecules in the ground state, this transformation of the orbitals leaves the total many-electron wave function unchanged.

The hybrid orbital description of the ground state is, therefore equivalent to the delocalized orbital description for ground state total energy and electron density, as well as the molecular geometry that corresponds to the minimum total energy value.

Different valence bond methods use either of the two representations, which have mathematically equivalent total many-electron wave functions and are related by a unitary transformation of the set of occupied molecular orbitals.