Molecular symmetry

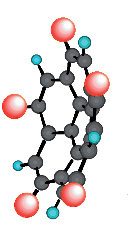

Molecular symmetry is a fundamental concept in chemistry, as it can be used to predict or explain many of a molecule's chemical properties, such as whether or not it has a dipole moment, as well as its allowed spectroscopic transitions.

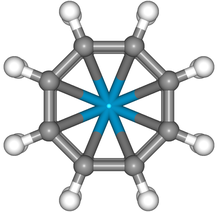

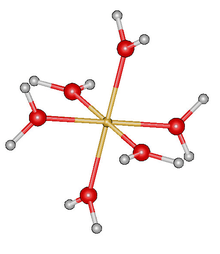

Symmetry is useful in the study of molecular orbitals, with applications to the Hückel method, to ligand field theory, and to the Woodward-Hoffmann rules.

[1][2][3][4][5] Another framework on a larger scale is the use of crystal systems to describe crystallographic symmetry in bulk materials.

There are many techniques for determining the symmetry of a given molecule, including X-ray crystallography and various forms of spectroscopy.

Because Ĉ1 is equivalent to Ê, Ŝ1 to σ and Ŝ2 to î, all symmetry operations can be classified as either proper or improper rotations.

For linear molecules, either clockwise or counterclockwise rotation about the molecular axis by any angle Φ is a symmetry operation.

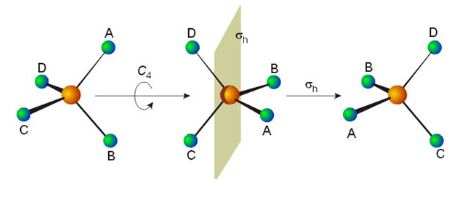

An example is the sequence of a C4 rotation about the z-axis and a reflection in the xy-plane, denoted σ(xy)C4.

[10] This classification system helps scientists to study molecules more efficiently, since chemically related molecules in the same point group tend to exhibit similar bonding schemes, molecular bonding diagrams, and spectroscopic properties.

It does not allow for tunneling between minima nor for the change in shape that can come about from the centrifugal distortion effects of molecular rotation.

The following table lists many of the point groups applicable to molecules, labelled using the Schoenflies notation, which is common in chemistry and molecular spectroscopy.

Only the identity operation E remains but this matrix just contains 1's on the leading diagonal (top left to bottom right) and 0's elsewhere.

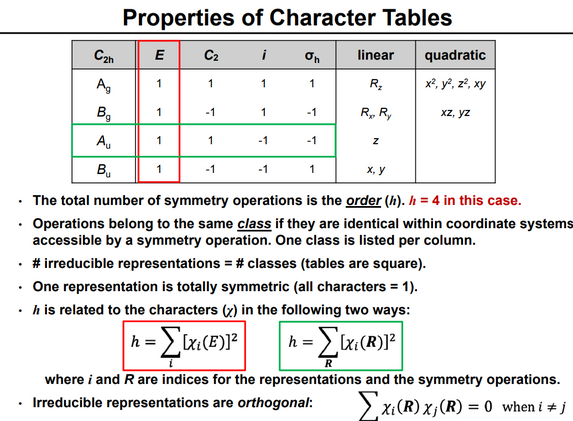

Robert Mulliken was the first to publish character tables in English (1933), and E. Bright Wilson used them in 1934 to predict the symmetry of vibrational normal modes.

One further thing to note about the irrep/character table above is the appearance of polar and axial base vector symbols on the right hand side.

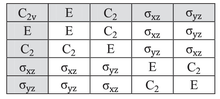

The irrep table for this symmetry group has the form below and, taking the 3D representations of the 4 operations in the order they appear in the diagram we obtain characters (3,-1,-3,1).

Symmetric point groups are divided into systems based on the increasing order of the main rotational axis from three to infinity.

The representations are labeled according to a set of conventions: Atomic orbital symmetry The tables also capture information about how the Cartesian basis vectors, rotations about them, and quadratic functions of them transform by the symmetry operations of the group, by noting which irreducible representation transforms in the same way.

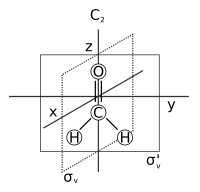

The 2px orbital of oxygen has B1 symmetry as in the fourth row of the character table above, with x in the sixth column).

When adapted for molecular work this table first divides point groups into three kinds: asymmetric, symmetric and spherical tops.

A further sub-division into systems is defined by the rotational group G in the leftmost column then into rows of Laue classes.

It is important to note that, since all the point groups of a Laue class have the same abstract structure, they also have exactly the same irreducible representations and character tables.

The total number of degrees of freedom for each symmetry species (or irreducible representation) can be determined.

[23] As discussed above in the section The molecular symmetry group, point groups are useful for classifying the vibrational and electronic states of rigid molecules (sometimes called semi-rigid molecules) which undergo only small oscillations about a single equilibrium geometry.

Longuet-Higgins introduced the molecular symmetry group (a more general type of symmetry group)[17] suitable not only for classifying the vibrational and electronic states of rigid molecules but also for classifying their rotational and nuclear spin states.

Further, such groups can be used to classify the states of non-rigid (or fluxional) molecules that tunnel between equivalent geometries[24] and to allow for the distorting effects of molecular rotation.

Tunneling between the conformations occurs at ordinary temperatures by internal rotation of one methyl group relative to the other.

Similarly, ammonia (NH3) has two equivalent pyramidal (C3v) conformations which are interconverted by the process known as nitrogen inversion.

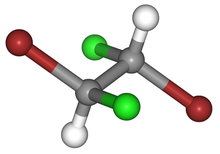

Additionally, the methane (CH4) and H3+ molecules have highly symmetric equilibrium structures with Td and D3h point group symmetries respectively; they lack permanent electric dipole moments but they do have very weak pure rotation spectra because of rotational centrifugal distortion.