Pipe organ

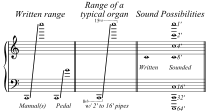

Most organs have many ranks of pipes of differing pitch, timbre, and volume that the player can employ singly or in combination through the use of controls called stops.

[3] The origins of the pipe organ can be traced back to the hydraulis in Ancient Greece, in the 3rd century BC,[4] in which the wind supply was created by the weight of displaced water in an airtight container.

[9] At that time, the pipe organ was the most complex human-made device[10]—a distinction it retained until it was displaced by the telephone exchange in the late 19th century.

[11] Pipe organs are installed in churches, synagogues, concert halls, schools, mansions, other public buildings and in private properties.

In the early 20th century, pipe organs were installed in theaters to accompany the screening of films during the silent movie era; in municipal auditoria, where orchestral transcriptions were popular; and in the homes of the wealthy.

A Syrian visitor describes a pipe organ powered by two servants pumping "bellows like a blacksmith's" played while guests ate at the emperor's Christmas dinner in Constantinople in 911.

Pepin's son Charlemagne requested a similar organ for his chapel in Aachen in 812, beginning its establishment in Western European church music.

The portative organs were small and created for secular use and made of light weight delicate materials that would have been easy for one individual to transport and play on their own.

Toward the middle of the 13th century, the portatives represented in the miniatures of illuminated manuscripts appear to have real keyboards with balanced keys, as in the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

[31] It had twenty bellows operated by ten men, and the wind pressure was so high that the player had to use the full strength of their arm to hold down a key.

[32] According to documentation from the 9th century by Walafrid Strabo, the organ was also used for music during other parts of the church service—the prelude and postlude the main examples—and not just for the effect of polyphony with the choir.

Builders such as Arp Schnitger, Jasper Johannsen, Zacharias Hildebrandt and Gottfried Silbermann constructed instruments that were in themselves artistic, displaying both exquisite craftsmanship and beautiful sound.

[42][43] This type of instrument was elaborately described by Dom Bédos de Celles in his treatise L'art du facteur d'orgues (The Art of Organ Building).

English organs evolved from small one- or two-manual instruments into three or more divisions disposed in the French manner with grander reeds and mixtures, though still without pedal keyboards.

[46] The Echo division began to be enclosed in the early 18th century, and in 1712, Abraham Jordan claimed his "swelling organ" at St Magnus-the-Martyr to be a new invention.

They returned to building mechanical key actions, voicing with lower wind pressures and thinner pipe scales, and designing specifications with more mixture stops.

When the organist depresses a key, the corresponding rod (called a tracker) pulls open its pallet, allowing wind to enter the pipe.

In such actions, an electromagnet attracts a small pilot valve which lets wind go to a bellows (the "pneumatic" component) which opens the pallet.

These can be used in combination with octave couplers to create innovative aural effects, and can also be used to rearrange the order of the manuals to make specific pieces easier to play.

At least one side of the box is constructed from horizontal or vertical palettes known as swell shades, which operate in a similar way to Venetian blinds; their position can be adjusted from the console.

The façade pipes may be plain, burnished, gilded, or painted[91] and are usually referred to as (en) montre within the context of the French organ school.

[95] For this reason, some modern builders, particularly those building instruments specializing in polyphony rather than Romantic compositions, avoid this unless the architecture of the room makes it necessary.

[96] The Buxheimer Orgelbuch, which dates from about 1470 and was compiled in Germany, includes intabulations of vocal music by the English composer John Dunstaple.

[100] In Spain, the works of Antonio de Cabezón began the most prolific period of Spanish organ composition,[101] which culminated with Juan Cabanilles.

The primary type of free-form piece in this period was the praeludium, as exemplified in the works of Matthias Weckmann, Nicolaus Bruhns, Böhm, and Buxtehude.

[103] The organ music of Johann Sebastian Bach fused characteristics of every national tradition and historical style in his large-scale preludes and fugues and chorale-based works.

[112] Because these concert hall instruments could approximate the sounds of symphony orchestras, transcriptions of orchestral works found a place in the organ repertoire.

[110] In the 20th-century symphonic repertoire, both sacred and secular,[114] continued to progress through the music of Marcel Dupré, Maurice Duruflé, and Herbert Howells.

[110] Other composers, such as Olivier Messiaen, György Ligeti, Jehan Alain, Jean Langlais, Gerd Zacher, and Petr Eben, wrote post-tonal organ music.

[115] Albert Schweitzer was an organist who studied the music of German composer Johann Sebastian Bach and influenced the Organ reform movement.