Organizational architecture

Organization design may involve strategic decisions, but is properly viewed as a path to effective strategy execution.

More powerful change happens when there are clear design objectives driven by a new business strategy or forces in the market require a different approach to organize resources.

The field is somewhat specialized in nature and many large and small consulting firms offer organization design assistance to executives.

Some companies attempt to establish internal staff resources aimed at supporting organization design initiatives.

There is a substantial body of literature in the field, arguably starting with the work of Peter Drucker in his examination of General Motors decades ago.

Other key thinkers built on Drucker's thinking, including Galbraith (1973), Nadler, et al. (1992) and Lawrence and Lorsch (1967).

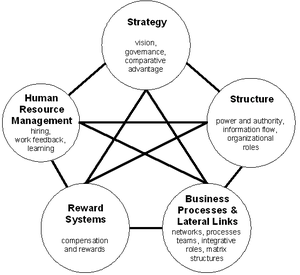

Many organizational experts argue for an integrated approach to these disciplines, including effective talent management practices.

Total systems often become complex because of the sheer size and nature of operations, but effectiveness and efficiency may still be achieved if each subsystem maintains its simplicity.

In some television sets, for example, it is common practice to replace an entire section of the network rather than try to find the faulty component.

When a system's objectives include achieving a particular task at the lowest possible cost, there must be some degree of trade-off between effectiveness and efficiency.

A basic consideration in the design of organizations is dividing work into reasonable tasks (differentiation) while giving simultaneous attention to coordinating these activities and unifying their results into a meaningful whole (integration).

For example, when units are similar in nature and function but are also relatively independent, the manager must base their decision on the most appropriate way to group activities according to their past experience.

[7] Designers with imagination have the best chance to group people and machines into workable combinations having the greatest efficiency and effectiveness within the recognized constraints.

[8] At this point, the designer must determine what has to be done to achieve the stated objective(s) and how the total task can be divided into meaningful units.

Of course, the balance between technical efficiency and the human factors that determine organizational climate should be included in making this decision.

The eventual success or failure of the project is somewhat predetermined by management's attitude and the relationship between the designers and those who must implement the process.

In the traditional view, the manager operated in a highly structured, rigid system having well-defined goals, clear-cut relationships, tight controls, and hierarchical information flows.

In the flexible (or open) systems view, the organization is not static but is continually evolving to meet both external and internal changes.

The manager's role is to develop a viable organization, cope with change, and help participants establish a dynamic equilibrium.

Leonard Sayles has expressed the manager's problem as follows: “The one enduring objective is the effort to build and maintain a predictable, reciprocating system of relationships, the behavioral patterns of which stay within reasonable physical limits.

In addition, it suggests that leadership patterns must be modified, particularly when dealing with professionals and highly trained specialists, and motivation must take the form of active, willing participation rather than forceful subjugation.

In this approach, the network of human independence required to accomplish a given task is based on the shared responsibility of all members of the subsystem.

Specialized staff groups have evolved to perform tasks such as long-range planning, organizational studies, and systems design.

Although the probability of success in implementation is enhanced considerably if management is vitally interested in the project, technical expertise and motivation for change are more likely to be found in staff groups.

The solution to the apparent dichotomy would seem to be a team approach,[10] with specialists supporting operating managers who are responsible for the project's success.