Oriental rug

The oldest known hand knotted rug which is nearly completely preserved, and can, therefore, be fully evaluated in every technical and design aspect is the Pazyryk carpet, dated to the 5th century BC.

The explorer Mark Aurel Stein found flat-woven kilims dating to at least the fourth or fifth century AD in Turpan, East Turkestan, China, an area which still produces carpets today.

Fragments of pile rugs from findspots in north-eastern Afghanistan, reportedly originating from the province of Samangan, have been carbon-14 dated to a time span from the turn of the second century to the early Sasanian period.

[28][29] In the early fourteenth century, Marco Polo wrote about the central Anatolian province of "Turcomania" in his account of his travels: "The other classes are Greeks and Armenians, who reside in the cities and fortified places, and gain their living by commerce and manufacture.

[citation needed] In the light of ancient sources and archaeological discoveries, it seems highly likely that the pile-woven carpet developed from one of the extra-weft wrapping weaving techniques, and was first woven by settled people.

Once the weaving has finished, the rug is further processed by fastening its borders, clipping the pile to obtain an even surface, and washing, which may use added chemical solutions to modify the colours.

[42] In the Middle East, rug wools come mainly from the fat-tailed and fat-rumped sheep races, which are distinguished, as their names suggest, by the accumulation of fat in the respective parts of their bodies.

For example, Persian Heriz or some Anatolian carpets may have low knot counts as compared to the extremely fine-woven Qom or Nain rugs, but provide artistic designs, and are resistant to wear.

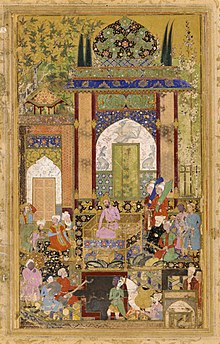

Prayer rugs also show highly symbolic smaller design elements like one or more mosque lamps, a reference to the Verse of Light in the Qur'an, or water jugs, potentially as a reminder towards ritual cleanliness.

[78] An Anatolian carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck's “Paele Madonna” painting was traced back to late Roman origins and related to early Islamic floor mosaics found in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.

[5] May H. Beattie[88] (1908–1997), a distinguished scholar in the field of carpet studies, wrote in 1976:[89] The symbolism of Oriental rug designs has recently been made the subject of a number of articles.

Many of the ideas put forward are of great interest, but to attempt to discuss such a subject without a profound knowledge of the philosophies of the East would be unwise, and could easily provide unreliable food for unbridled imaginations.

In 1967, the British archaeologist James Mellaart claimed to have found the oldest records of flat woven kilims on wall paintings he discovered in the Çatalhöyük excavations, dated to circa 7000 BC.

[91] The drawings Mellaart claimed to have made before the wall paintings disappeared after their exposure showed clear similarities to nineteenth century designs of Turkish flatweaves.

It is today understood as a design of stylized carnation flowers, and its development can be traced back in a detailed and unbroken line to Ottoman court carpets of the sixteenth century.

This is especially true for Turkmen pile woven textiles, which depict a variety of different medallion-like polygonal patterns called Gul, arranged in rows all over the field.

A technical classification for Persian carpets is based on material used for warps, wefts, and pile, spinning and plying of the yarn, dyeing, weaving technique, and aspects of finishing including the ways how the sides (selvedges) and ends are reinforced against wear.

In the Soviet socialistic economy, carpet production was organized in industrial lines in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Daghestan and Georgia, which used standardized designs based on traditional motifs, provided on scalepaper cartoons by specialized artists.

Detailed ethnographic information is available from the works of ethnologists like Vsevolod Miller and Soviet Russian surveys conducted by the Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography (cited in[121]) However, during the long period of industrial production, the connection between specific designs and their ethnic and geographic origins may have been lost.

[120] From a Western perspective, when scientific interest started to develop in Oriental rugs by the end of the nineteenth century, the Caucasian regions, being part of the Soviet Union, closed up to the West.

[126] The Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century AD led to the destruction of the cities and agricultural irrigation systems, and reduced the Turkmen people to a nomadic lifestyle which they have kept throughout their later history, living at the borders of more powerful states like the Persian Empire, the Khwarazmian dynasty, and the Khanate of Bukhara.

Within general activities to revive the ancient tradition of hand-spinning, natural dyeing, and hand weaving, projects to support refugees from Afghanistan have taken a part in the “carpet renaissance”.

Other thirteenth-century European travellers who journeyed to the court of the Mongol Empire were André de Longjumeau, William of Rubruck and Giovanni da Pian del Carpine with Benedykt Polak.

In a series of letters[137] from Venice dated 18 August - 13 October 1506,[138] the Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer mentions "two nice and large" carpets which he bought for a friend amongst other luxury goods.

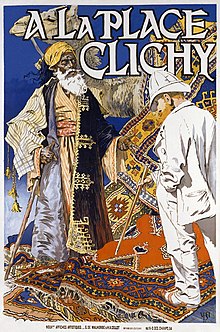

Objects of courtly representation and prestige initially, oriental rugs became affordable to wider groups of European citizens with the growing wealth and influence of merchant families and private persons.

[34] Since the late nineteenth century, attempts were made to determine the date when specific rugs were woven, and carpets were identified with designs similar to these reproduced in the paintings.

[75] Village or nomadic rugs were not depicted in paintings aiming to represent dignity and prestige, and not until the mid twentieth century was their artistic and art historic value appreciated in the Western World.

The high price that was to be paid for the Ardabil carpet required public collection of money, and Oriental rugs came to be understood as objects of great value by a larger audience.

With Wilhelm von Bode as its first director, his successors Friedrich Sarre, Ernst Kühnel, and Kurt Erdmann created and established the “Berlin School” of history of Islamic Art.

In 1932, a group of collectors and rug enthusiasts, amongst them Arthur Dilley, Joseph McMullan, and Maurice Dimand, then curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, founded the Hajji Baba Club.