Anatolian rug

Distinct types of rugs have been woven ever since in court manufactures and provincial workshops, village homes, tribal settlements, or in the nomad's tent.

Controversy arose over the accuracy of the claim[2] that the oldest records of flat woven kilims come from the Çatalhöyük excavations, dated to circa 7000 BC.

[3] The excavators' report[4] remained unconfirmed, as it states that the wall paintings depicting kilim motifs had disintegrated shortly after their exposure.

They weave the finest and handsomest carpets in the world, and also a great quantity of fine and rich silks of cramoisy and other colours, and plenty of other stuffs.

The style of the Seljuq rugs has parallels amongst the architectural decoration of contemporaneous mosques such as those at Divriği, Sivas, and Erzurum, and may be related to Byzantine art.

One of the Turkoman tribes of the Beylik group, the Tekke settled in South-western Anatolia in the eleventh century, and moved back to the Caspian sea later.

The Tekke tribes of Turkmenistan, living around Merv and the Amu Darya during the 19th century and earlier, wove a distinct type of carpet characterized by stylized floral motifs called guls in repeating rows.

Suleiman the Magnificent, the tenth Sultan (1520-1566), invaded Persia and forced the Persian Shah Tahmasp (1524–1576) to move his capital from Tabriz to Qazvin, until the Peace of Amasya was agreed upon in 1555.

One of these carpets was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art[14] which parallels a painting by the Sienese artist Gregorio di Cecco: "The Marriage of the Virgin", 1423.

They are characterized by large dark blue star shaped primary medallions in infinite repeat on a red ground field containing a secondary floral scroll.

The Transylvanian church records, as well as Netherlandish paintings from the seventeenth century which depict in detail carpets with this design, allow for precise dating.

Transylvanian vigesimal accounts, customs bills, and other archived documents provide evidence that these carpets were exported to Europe in large quantities.

[35] Pieter de Hoochs 1663 painting "Portrait of a family making music" depicts an Ottoman prayer rug of the "Transylvanian" type.

The typical "palace carpet" features intricate floral designs, including the tulip, daisy, carnation, crocus, rose, lilac, and hyacinth.

In an attempt to save on resources and cost, and maximise on profit in a competitive market environment, synthetic dyes, non-traditional weaving tools like the power loom, and standardized designs were introduced.

Women learn their weaving skills at an early age, taking months or even years to complete the pile rugs and flat woven kilims that were created for their use in daily life.

This often results in faster pile wear in areas dyed in dark brown colours, and may create a relief effect in antique Turkish carpets.

Specific elements are closely related to the history of Turkic peoples and their interaction with surrounding cultures, in their central Asian origin as well as during their migration, and in Anatolia itself.

Carpets from the Bergama and Konya areas are considered as most closely related to earlier Anatolian rugs, and their significance in the history of the art is now better understood.

Recently, Brüggemann further elaborated on the relationship between Chinese and Turkic motifs like the "cloud band" ornament, the origin of which he relates to the Han dynasty.

[54] A Turkish carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck's "Paele Madonna" painting was traced back to late Roman origins and related to early Islamic floor mosaics found in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.

[55] The architectural elements seen in the Khirbat al-Mafjar complex are considered exemplary for the continuation of pre-Islamic, Roman designs in early Islamic art.

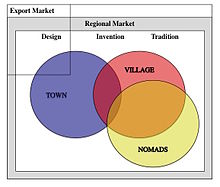

[25] Elements of town design were often reproduced in rural production, and integrated by the village weavers into their own artistic tradition by a process called stylization.

The Mevlana Museum in Konya has a large collection of Anatolian rugs, including some of the carpet fragments found in the Alaeddin and Eşrefoğlu Mosque.

The Konya-Selçuk carpet tradition makes use of a lean octagonal medallion in the middle of the field, with three opposed geometrical forms crowned by tulips.

Obruk rugs show the typical Konya design and colours, but their ornaments are more bold and stylized, resembling the Yürük traditions of the weavers from this village.

Typically, an elaborate pendant representing either a Mosque lamp or a triangular protective amulet ("mosca") hanging from the prayer niche adorns the field.

The foundation of their main border is often dyed in corrosive brown, which caused deterioration of the carpet pile in these areas, and produces a relief effect.

Another type of design often seen in Karapinar runners is composed of geometric hexagonal primary motifs arranged on top of each other, in subdued red, yellow, green, and white.

The towns of Hakkâri and Erzurum were market places for Kurdish kilims, rugs and smaller weavings like cradles, bags (heybe) and tent decorations.