Orthodontics

[4][5] The main reason for the prevalence of these malocclusions is diets with less fresh fruit and vegetables and overall softer foods in childhood, causing smaller jaws with less room for the teeth to erupt.

[6] Treatment may require several months to a few years and entails using dental braces and other appliances to gradually adjust tooth position and jaw alignment.

Evidence from Greek and Etruscan materials suggests that attempts to treat this disorder date back to 1000 BC, showcasing primitive yet impressively well-crafted orthodontic appliances.

Being a major presence in American dentistry during the latter half of the 19th century, not only was Kingsley one of the early users of extraoral force to correct protruding teeth, but he was also one of the pioneers for treating cleft palates and associated issues.

Initially focused on prosthodontics, he taught in Pennsylvania and Minnesota before directing his attention towards dental occlusion and the treatments needed to maintain it as a normal condition, thus becoming known as the "father of modern orthodontics".

Not only were there issues related to aesthetics, but it usually proved impossible to keep a precise occlusal relationship achieved by forcing teeth together over extended durations with the use of robust elastics, something Angle and his students had previously suggested.

Charles Tweed[11] in America and Raymond Begg[12] in Australia (who both studied under Angle) re-introduced dentistry extraction into orthodontics during the 1940s and 1950s so they could improve facial esthetics while also ensuring better stability concerning occlusal relationships.

[13] In the postwar period, cephalometric radiography[14] started to be used by orthodontists for measuring changes in tooth and jaw position caused by growth and treatment.

It became evident that orthodontic therapy could adjust mandibular development, leading to the formation of functional jaw orthopedics in Europe and extraoral force measures in the US.

The American Journal of Orthodontics was created for this purpose in 1915; before it, there were no scientific objectives to follow, nor any precise classification system and brackets that lacked features.

It's aptly named after this feature: the angle of the slot and thickness of the bracket base ultimately determine where each tooth is situated with little need for extra manipulation.

This innovative technology allowed for the utilization of rectangular archwires to precisely control tooth movement during the finishing stages after initial treatment with round wires.

Edward H. Angle made a significant contribution to the dental field when he released the 7th edition of his book in 1907, which outlined his theories and detailed his technique.

[21] This device was different from any other appliance of its period as it featured a rigid framework to which teeth could be tied effectively in order to recreate an arch form that followed pre-defined dimensions.

[8] Dubbed the "bone-growing appliance", this contraption was theorized to encourage healthier bone growth due to its potential for transferring force directly to the roots.

This lack of understanding posed a considerable challenge to dental professionals; they were unable to make corrections to an excessive Spee curve in bicuspid teeth.

Unparalleled to its counterparts, what made the ribbon arch instantly popular was that its archwire had remarkable spring qualities and could be utilized to accurately align teeth that were misaligned.

[25] Following extensive trials, it was concluded that dimensions of 22 × 28 mils were optimal for obtaining excellent control over crown and root positioning across all three planes of space.

[8] Prior to Angle, the idea of fitting attachments on individual teeth had not been thought of, and in his lifetime, his concern for precisely positioning each tooth was not highly appraised.

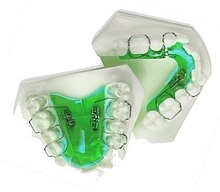

In addition to using fingersprings for repositioning teeth with a range of removable devices, two main appliance systems were very popular in the early part of the 20th century.

Labiolingual appliances use bands on the first molars joined with heavy lingual and labial archwires affixed with soldered fingersprings to shift single teeth.

Returning to Australia in the 1920s, the renowned orthodontist, Raymond Begg, applied his knowledge of ribbon arch appliances, which he had learned from the Angle School.

On top of this, Begg recognized that extracting teeth was sometimes vital for successful outcomes and sought to modify the ribbon arch appliance to provide more control when dealing with root positioning.

Given the discrepancies in inclination of facial surfaces across individual teeth, placing a twist, otherwise known as third-order or torque bends, into segments of each rectangular archwire was initially required with the edgewise appliance.

These brackets already have angulation and torque values built in so that each rectangluar archwire can be contorted to form a custom fit without inadvertently shifting any correctly positioned teeth.

Orthodontists offer a wide range of treatment options to straighten crooked teeth, fix irregular bites, and align the jaws correctly.

In growing patients, there are more options to treat skeletal discrepancies, either by promoting or restricting growth using functional appliances, orthodontic headgear, or a reverse pull facemask.

[39] Orthodontic headgear, sometimes referred to as an "extra-oral appliance", is a treatment approach that requires the patient to have a device strapped onto their head to help correct malocclusion—typically used when the teeth do not align properly.

[52] After completing a degree in orthodontics, specialists are required to be registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) in order to practice.

[63] Obtaining a Certificate of Completion of Specialty Training (CCST) allows an orthodontic specialist to be registered under the General Dental Council (GDC).