Megalodon

As the shark preferred warmer waters, it is thought that oceanic cooling associated with the onset of the ice ages, coupled with the lowering of sea levels and resulting loss of suitable nursery areas, may have also contributed to its decline.

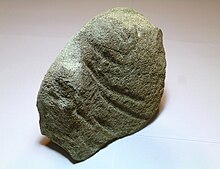

They were a valued artifact amongst pre-Columbian cultures in the Americas for their large sizes and serrated blades, from which they were modified into projectile points, knives, jewelry, and funeral accessories.

[11] The purported tongues were later thought in a 12th-century Maltese tradition to have belonged to serpents that Paul the Apostle turned to stone while shipwrecked there, and were given antivenom powers by the saint.

Use of megalodon teeth for this purpose became widespread among medieval and Renaissance nobility, who fashioned them into protective amulets and tableware to purportedly detoxify poisoned liquids or bodies that touched the stones.

The earliest scientific argument for this view was made by Italian naturalist Fabio Colonna, who in 1616 published an illustration of a Maltese megalodon tooth alongside a great white shark's and noted their striking similarities.

[13] The shark tooth argument was academically raised again during the late 17th century by English scientists Robert Hooke, John Ray, and Danish naturalist Niels Steensen (Latinized Nicholas Steno).

The work remained unpublished in Steensen's time due to Mercati's premature death, and the former reused the two illustrations per suggestion by Carlo Roberto Dati, who thought a depiction of the actual dissected shark was unsuitable for readers.

[2] Formal description of the species was published in an 1843 volume, where Agassiz revised the name to Carcharodon megalodon as its teeth were far too large for the former genus and more alike to the great white shark.

[29]: 30 The genus Palaeocarcharodon was erected alongside Procarcharodon to represent the beginning of the lineage, and, in the model wherein megalodon and the great white shark are closely related, their last common ancestor.

[28]: 70 Another model of the evolution of this genus, also proposed by Casier in 1960, is that the direct ancestor of the Carcharocles is the shark Otodus obliquus, which lived from the Paleocene through the Miocene epochs, 60 to 13 Mya.

[29]: 17 [20][33] Some authors suggest that C. auriculatus, C. angustidens, and C. chubutensis should be classified as a single species in the genus Otodus, leaving C. megalodon the sole member of Carcharocles.

The discovery of fossils assigned to the genus Megalolamna in 2016 led to a re-evaluation of Otodus, which concluded that it is paraphyletic, that is, it consists of a last common ancestor but it does not include all of its descendants.

Shimada stated that the previously proposed methods were based on a less-reliable evaluation of the dental homology between megalodon and the great white shark, and that the growth rate between the crown and root is not isometric, which he considered in his model.

[58] Among several specimens found in the Gatún Formation of Panama, one upper lateral tooth was used by other researchers to obtain a total length estimate of 17.9 meters (59 ft) using this method.

[25][40] In 2021, Victor J. Perez, Ronny M. Leder, and Teddy Badaut proposed a method of estimating total length of megalodon from the sum of the tooth crown widths.

The researchers noted that the 2002 Shimada crown height equations produce wildly varying results for different teeth belonging to the same shark (range of error of ± 9 metres (30 ft)), casting doubt on some of the conclusions of previous studies using that method.

[60] In addition, a 2.7-by-3.4-meter (9 by 11 ft) megalodon jaw reconstruction developed by fossil hunter Vito Bertucci contains a tooth whose maximum height is reportedly over 18 centimeters (7 in).

Diagnostic characteristics include a triangular shape, robust structure, large size, fine serrations, a lack of lateral denticles, and a visible V-shaped neck (where the root meets the crown).

[46][65] In 2021, Antonio Ballell and Humberto Ferrón used Finite Element Analysis modeling to examine the stress distribution of three types of megalodon teeth and closely related mega-toothed species when exposed to anterior and lateral forces, the latter of which would be generated when a shark shakes its head to tear through flesh.

The resulting simulations identified higher levels of stress in megalodon teeth under lateral force loads compared to its precursor species such as O. obliquus and O. angusteidens when tooth size was removed as a factor.

[75] Megalodon bite marks on whale fossils suggest that it employed different hunting strategies against large prey than the great white shark.

[75] There is also evidence that a possible separate hunting strategy existed for attacking raptorial sperm whales; a tooth belonging to an undetermined 4 m (13 ft) physeteroid closely resembling those of Acrophyseter discovered in the Nutrien Aurora Phosphate Mine in North Carolina suggests that a megalodon or O. chubutensis may have aimed for the head of the sperm whale in order to inflict a fatal bite, the resulting attack leaving distinctive bite marks on the tooth.

He also estimated that the slowing or cessation of somatic growth in megalodon occurred around 25 years of age, suggesting that this species had an extremely delayed sexual maturity.

[48] Megalodon, like contemporaneous sharks, made use of nursery areas to birth their young in, specifically warm-water coastal environments with large amounts of food and protection from predators.

Three tooth marks apparently from a 4-to-7-meter (13 to 23 ft) long Pliocene shark were found on a rib from an ancestral blue or humpback whale that showed evidence of subsequent healing, which is suspected to have been inflicted by a juvenile megalodon.

The largest fluctuation of sea levels in the Cenozoic era occurred in the Plio-Pleistocene, between around 5 million to 12 thousand years ago, due to the expansion of glaciers at the poles, which negatively impacted coastal environments, and may have contributed to its extinction along with those of several other marine megafaunal species.

[112] Paleontologist Robert Boessenecker and his colleagues rechecked the fossil record of megalodon for carbon dating errors and concluded that it disappeared circa 3.5 million years ago.

[23] Boessenecker and his colleagues further suggest that megalodon suffered range fragmentation due to climatic shifts,[23] and competition with white sharks might have contributed to its decline and extinction.

[118] Multiple compounding environmental and ecological factors including climate change and thermal limitations, collapse of prey populations and resource competition with white sharks are believed to have contributed to decline and extinction of megalodon.

[122] These claims have been discredited, and are probably teeth that were well-preserved by a thick mineral-crust precipitate of manganese dioxide, and so had a lower decomposition rate and retained a white color during fossilization.