Ottoman Turkish alphabet

The various Turkic languages have been written in a number of different alphabets, including Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, Latin and other writing systems.

[2] Other Oghuz Turkic languages such as Azerbaijani and Turkmen enjoyed a high degree of written mutual intelligibility as the Ottoman Alphabet catered to anachronistic Turkic consonants and spellings that demonstrated Anatolian Turkish' shared history with Azerbaijani and Turkmen.

At the start of the 20th century, similar proposals were made by several writers associated with the Young Turk movement, including Hüseyin Cahit, Abdullah Cevdet and Celâl Nuri.

[3] In 1917, Enver Pasha introduced a revised alphabet, the hurûf-ı munfasıla representing Turkish sounds more accurately; it was based on Arabic letter forms, but written separately, not joined cursively.

[4] The romanization issue was raised again in 1923 during the İzmir Economic Congress of the new Turkish Republic, sparking a public debate that was to continue for several years.

It was argued that romanization of the script would detach Turkey from the wider Islamic world, substituting a foreign (European) concept of national identity for the confessional community.

Some suggested that a better alternative might be to modify the Arabic script to introduce extra characters for better representing Turkish vowels.

[5]In 1926, the Turkic republics of the Soviet Union adopted the Latin script, giving a major boost to reformers in Turkey.

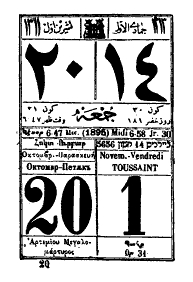

[6][7] The change was formalized by the Law on the Adoption and Implementation of the Turkish Alphabet,[8] passed on November 1, 1928, and effective on January 1, 1929.

The soft consonant letters, ت س ك گ ه, are found in front vowel (e, i, ö, ü) contexts; the hard, ح خ ص ض ط ظ ع غ ق, in back vowel (a, ı, o, u) contexts; and the neutral, ب پ ث ج چ د ذ ر ز ژ ش ف ل م ن, in either.

[11][12][page needed] Therefore, some Ottoman Turkish dictionaries and language textbooks sought to address this issue by introducing new notations and letters.

The necessity arose from the fact that this was a solely Turkish dictionary, and thus Şemseddin Sâmi avoided using any Latin or other foreign notations.

This book also employs specific notations and letters in order to distinguish between different phonemes, so as to match with the Modern Turkish alphabet.

Karamanlides (Orthodox Turks in Central Anatolia around Karaman region) used Greek letters for Ottoman Turkish.