PRO (linguistics)

The presence of PRO in non-finite clauses lacking overt subjects allows a principled solution for problems relating to binding theory.

[3] Instead, PRO is taken to be in complementary distribution with overt subjects because it is the only item that is able to carry null case which is checked for by non-finite tense markers (T), for example the English to in control infinitives.

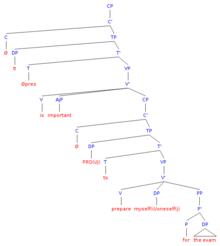

The following tree diagrams of examples (1) and (2) show how PRO occupies the subject position of non-finite clauses.

Therefore, in the absence of an overt subject, the null category PRO helps to satisfy the theta criterion.

[1] The tree diagram (3) represents how PRO satisfies the theta criterion of examine by being the DPagent in the non-finite clause.

The claim that non-finite clauses have a phonologically null PRO subject is in part motivated by binding theory — in particular, the idea that an anaphor requires a local antecedent to be present.

If the null subject PRO were not present in examples like (4a) and (4b), then non-finite clauses would contain anaphors that lacked a local antecedent, and incorrectly predicting that such sentences to be ungrammatical.

The (a) examples show contexts where an overt DP subject is ungrammatical in the specifier position of the TP (tense phrase).

Baltin (1995) argues that the tense marker to does not have an EPP feature, and that therefore PRO does not move to Spec-TP; this yields the structure in (14b).

[11] In contrast, Radford (2004) argues that infinitival to does have an EPP feature, and that therefore PRO must move to Spec-TP, as in (14c).

[3] Radford justifies moving PRO to Spec-TP on the basis of the binding properties of certain sentences.

Major points of similarities and differences center on the following: In English, PRO is treated as caseless, and can be controlled by the subject (17a) or object (17b) of the verb in the main clause) or it may be uncontrolled (17c).

Bræðrunumbrothers.the.D.M.PLlikaðilikedillaill[aðtoPRONverabeekkinotbáðirboth.N.M.PLkosnir].electedBræðrunum likaði illa [að PRO vera ekki báðir kosnir].brothers.the.D.M.PL liked ill to N be not both.N.M.PL elected'The brothers disliked not being both elected.

(Sigurðsson and Sigursson, 2008: 410 (18))PRO in adjunct clauses in Spanish can be controlled by dative experiencer subjects.

(Montrul 1998: 32 (12))In French, PRO can be controlled by dative experiencers in object position in an adjunct clause.

In (21), the dative experiencer object Pierre controls the PRO-subject of the adjunct clause avant même de PRO y avoir été initié 'before even having been initiated to it'.

(Montrul 1998: 33 (13))The structure of sentences like (21) can lead to an ambiguous interpretation if the subject is animate.

[10] These principles allow control verbs to be explained by movement and what had previously been analyzed as PRO is instead treated as the trace of DP/NP-movement.

Consider the example in (24): to derive (24a) the DP John moves through several positions, and checks a θ-role at each landing site; this is shown in (24b).

In the movement analysis, multiple θ-role assignment does the same work as allowing obligatory control of a PRO subject.

Since non-obligatory control occurs when movement is not permitted, it may be treated as an elsewhere case: little pro inserted as a last resort measure to rescue the derivation if an overt subject is missing.

[14] A:accusative D:dative DFT:default N:nominative (See Syntactic abbreviation key for more information.)