Pagan kingdom

Over the next two hundred years, the small principality gradually grew to absorb its surrounding regions until the 1050s and 1060s when King Anawrahta founded the Pagan Empire, presumably for the first time unifying under one polity the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery.

Theravada Buddhism slowly began to spread to the village level although Tantric, Mahayana, Brahmanic, and animist practices remained heavily entrenched at all social strata.

[5] The kingdom went into decline in the mid-13th century as the continuous growth of tax-free religious wealth by the 1280s had severely affected the crown's ability to retain the loyalty of courtiers and military servicemen.

[10] The Glass Palace Chronicle goes on to relate that around 107 AD, Thamoddarit (သမုဒ္ဒရာဇ်), nephew of the last king of Sri Ksetra, founded the city of Pagan (formally, Arimaddana-pura (အရိမဒ္ဒနာပူရ), lit.

[14] Archaeological evidence shows that as early as the 2nd century BC the Pyu had built water-management systems along secondary streams in central and northern parts of the Irrawaddy basin and had founded one of Southeast Asia's earliest urban centres.

)[25] Thant Myint-U summarises that "the Nanzhao Empire had washed up on the banks of the Irrawaddy, and would find a new life, fused with an existing and ancient culture, to produce one of the most impressive little kingdoms of the medieval world.

In the first decade of his reign, he invested much effort into turning the arid parched lands of central Myanmar into a rice granary, successfully building/enlarging weirs and canals, mainly around the Kyaukse district,[36] east of Pagan.

Anawrahta's victory terracotta votive tablets emblazoned with his name in Sanskrit have been found along the Tenasserim coastline in the south, Katha in the north, Thazi in the east and Minbu in the west.

Over his 27-year reign, Pagan's influence reached further south to the Strait of Malacca,[45] at least to the Salween river in the east and below the current China border in the farther north.

Thus the throne lost resources needed to retain the loyalty of courtiers and military servicemen, inviting a vicious circle of internal disorders and external challenges by Mons, Mongols and Shans.

In the south, Wareru, the man who had seized the governorship of Martaban in 1285, consolidated Mon-speaking regions of Lower Myanmar, and declared Ramannadesa (Land of the Mon) independent on 30 January 1287.

[52] The chronicles report that the eastern territories including trans-Salween states of Keng Hung, Kengtung and Chiang Mai stopped paying tribute[53] although most scholars attribute Pagan's limits to the Salween.

[62] Pagan's government can be generally described by the mandala system in which the sovereign exercised direct political authority in the core region (pyi, lit.

[63][64] Surrounding the core region were the naingngans or tributary states, governed by local hereditary rulers as well as Pagan appointed governors, drawn from princely or ministerial families.

In general, the king of Pagan received a periodic nominal tribute but had "no substantive authority", for example, on such matters as the selection of deputies, successors, or levels of taxation.

Most of the field levy served in the infantry but the men for the elephantry, cavalry, and naval corps were drawn from specific hereditary villages that specialised in respective military skills.

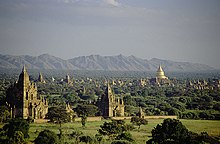

According to Victor Lieberman, the prosperous economy supported "a rich Buddhist civilization whose most spectacular feature was a dense forest of pagodas, monasteries, and temples, totaling perhaps 10,000 brick structures, of which the remains of over 2000 survive.

Burman immigrants are believed to have either introduced new water management techniques or greatly enhanced existing Pyu system of weirs, dams, sluices, and diversionary barricades.

The earliest irrigation projects focused on Kyaukse where Burmans built a large number of new weirs and diversionary canals, and Minbu a similarly well-watered district south of Pagan.

Trade was not the main engine of economic growth for much of the Pagan period although its share of the economy probably increased in the 13th century when the agricultural sector stopped growing.

[80] At Pagan and at main provincial centres, Buddhist temples supported an increasingly sophisticated Pali scholarship, which specialised in grammar and philosophical-psychological (abhidhamma) studies, and which reportedly won the admiration of Sinhalese experts.

Besides religious texts, Pagan's monks read works in a variety of languages on prosody, phonology, grammar, astrology, alchemy, and medicine, and developed an independent school of legal studies.

A key turning point came c. 1056 when the Buddhist school won the royal patronage of an ascendant empire with Anawrahta's conversion from his native Tantric Buddhism.

More recently, however, Aung-Thwin has argued forcefully that Anawrahta's conquest of Thaton is a post-Pagan legend without contemporary evidence, that Lower Myanmar in fact lacked a substantial independent polity prior to Pagan's expansion, and that the Mon influence on the interior is greatly exaggerated.

The low levels of interaction in turn retarded literacy in Burmese, and limited most commoners' understanding of Buddhism to non-textual means: paintings at the great temples, pageants, folkloric versions of the Jataka stories of the Buddha's life, etc.

Contemporary inscriptions show that the Aris ate evening meals, and presided over public ceremonies where they drank liquor and where cattle and other animals were sacrificed—activities considered scandalous by Burmese Buddhist norms of the 18th and 19th centuries.

For example, ceremonial animal slaughter and alcohol consumption long antedated the Burmans' arrival, and continued in remote parts of mainland and maritime Southeast Asia until recent times.

Burman immigrants are believed to have either introduced new water management techniques or greatly enhanced existing Pyu system of weirs, dams, sluices, and diversionary barricades.

[74][98] Pagan's several water management projects in the dry zone provided Upper Myanmar with an enduring economic base to dominate the rest of the country.

[105] Only in the former Khmer Empire, did the Thai/Lao ethnicity and Thai/Lao languages spread permanently at the expense of the Mon-Khmer speaking peoples, not unlike the Burman takeover of the Pyu realm four centuries earlier.